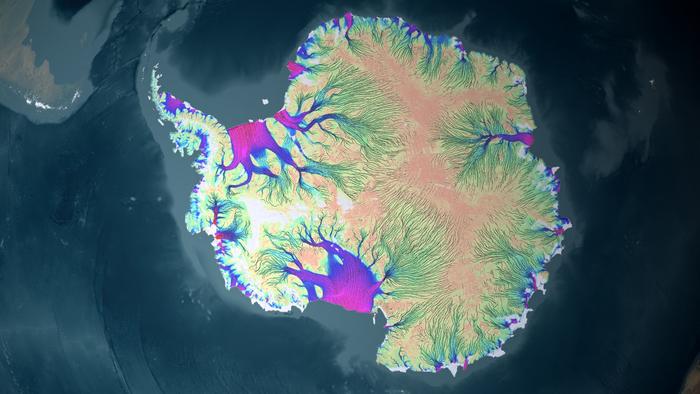

As the planet warms, the Antarctic ice sheets melt, contributing to rising sea levels around the world.

The Antarctic holds enough frozen water to raise the world’s sea level by 190 feet, so accurate predictions on how the ice sheets will currently move and melt are essential to protecting coastal areas.

However, most climate models struggle to accurately simulate Antarctic ice movements due to the sparse data and the complexity of interactions between oceans, air and frozen surfaces.

In the new study, researchers at Stanford University used machine learning to analyze high-resolution remote sensing data of Antarctic ice movement for the first time.

Using AI to understand our climate will reveal some of the fundamental physics that manage the large-scale movement of Antarctic ice sheets, and will help us improve our predictions about how the continent will change in the future.

The dynamics of the Antarctic ice sheet

The Antarctic ice sheet, which is almost twice the size of Australia, is the largest ice block on Earth, and is almost twice as large as Australia, functions like a planetary sponge, stabilizing the surface of the sea by storing freshwater like ice.

To understand the movement of Antarctic ice sheets, which are rapidly shrinking each year, existing models usually rely on assumptions regarding the mechanical behavior of ICEs derived from laboratory experiments.

However, Antarctic ice is much more complicated than what you can simulate in the lab. Ice formed from seawater has different properties than ice formed from compressed snow, and ice sheets may contain large cracks, air pockets, or other inconsistencies that affect movement.

“These differences affect the overall mechanical behavior of the ice sheet, so-called constitutive models, in ways that are not captured in existing models or lab settings,” explained Ching-Yao Lai, assistant professor of geophysics at Stanford Doler’s School of Sustainability and senior author of the paper.

Instead, the team built a machine learning model to analyze the large-scale movement and thickness of ice recorded on satellite images and plane radar between 2007 and 2018.

Researchers ask the model to fit remote sensing data and adhere to existing laws of physics governing ice movement, which they use to derive new constitutive models to explain ice viscosity, i.e. resistance to movement and flow.

Compression and strain

Researchers focused on five ice shelves in Antarctica. It is an ice floating platform that extends from land glaciers to the ocean and holds down most of Antarctic glacial ice.

They found that the portion of the ice shelf closest to the continent is compressed, and the constituent models for these regions are in considerable agreement with laboratory experiments.

However, as the ice gets further away from the continent, it begins to be drawn into the ocean. Strain causes ice in this area to have different physical properties in different directions.

“Our research reveals that most ice shelves are anisotropic,” said Yongji Wang, the first researcher to do the work as a postdoctoral researcher in the LAI lab.

“The compression zone – parts near grounded ice – account for less than 5% of the ice shelves. The other 95% are expansion zones and do not follow the same law.”

An accurate understanding of the movement of Antarctic ice sheets becomes more important as global temperatures increase. Sea rises have already increased flooding in lowlands and islands, promoting coastal erosion and exacerbating damage from hurricanes and other severe storms.

The Benefits of AI in Climate Modeling

The study authors still don’t know exactly what the extended zone is causing the anisotropy, but they intend to continue improving their analysis with additional Antarctica data as it becomes available.

Researchers can also use these findings to understand the stress that can cause clefts and births, or as a starting point for incorporating complexity through ice sheet models.

This work is the first step in building a model that more accurately simulates the conditions that may be faced in the future.

Researchers believe that the combination of observational data with established physical laws and deep learning can be used to reveal the physics of other natural processes with extensive observational data.

They hope that their methods will support additional scientific discoveries and lead to new collaborations with the Earth Science community.

Rai concluded: “We are trying to show that we can actually use AI to learn something new.

“It still needs to be bound by some physical laws, but this combined approach has allowed us to reveal the physics of ice beyond what was previously known, and truly promote a new understanding of the processes of Earth and planets in a natural environment.”

Source link