The Neanderthals who bred with our ancestors may have given them DNA that will cause the brain to develop a fatal condition that could swell from the skull.

The disorder known as Chiari malformation type I affects the lower part of the cerebellum, a part of the brain that helps control movement. In people in this state, the cerebellum protrudes from the hole at the base of the skull into the spine. Symptoms can include headaches, neck pain and dizziness, and too much brain can be fatal.

In mild cases, symptoms may be treated with muscle relaxants, but in severe cases, doctors can treat the condition by removing bone masses from the brain and vertebrae of Mark Collado, a paleontologist at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia.

You might like it

Discovered in the 1800s by Austrian pathologist Hans Chiari, the disorder is thought to affect about 1 in 1,000 people. However, recent imaging studies suggest that it is very common and can occur in more than one in 100 people. Most of the time, they avoid notifications because they don’t reveal any major symptoms, Corrado said.

Chiari’s deformity type 1 occurs when the occipital bone behind a person’s skull is not large enough to properly hold the brain, but becomes pinching the bulging area. However, the cause of the abnormally small occipital bone remains unknown.

In a 2013 study, scientists proposed that the condition was the result of mating between Eurasian Neanderthals and modern people. Previous studies have found that such mixing contains 1.5% to 2% Neanderthal DNA in all non-African genomes.

Related: “Nanderthals more than humans”: How your health depends on DNA from our long-standing ancestors

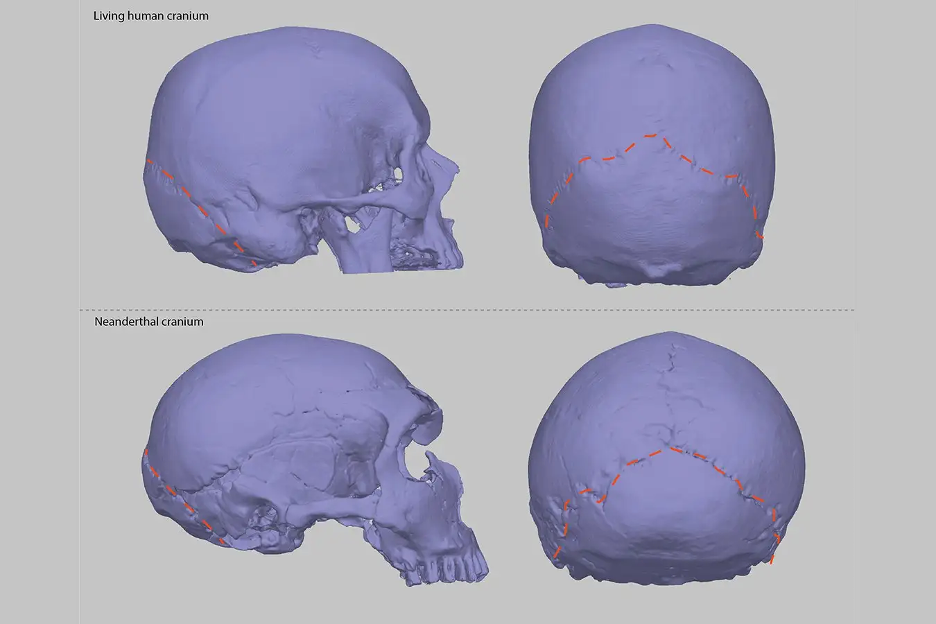

Modern human skulls are spherical and have a rounded back of the skull, but Neanderthal skulls are relatively long and the skull’s back is more angular. A 2013 study suggested that Neanderthal DNA could affect the development of modern human skulls, leading to discrepancies between the brain and skull size and shape, particularly the base of the skull.

To explore this idea, a new study examined 3D CT scans of the skulls of 103 living people. The researchers compared these skulls to eight fossil skulls of modern-day relatives, including Neanderthals, Homo Heidelbergensis, Homo erectus and prehistoric Homo sapiens.

Author Kimberly Promp, a osteologist at the University of the Philippines Diliman, found that the skulls of modern humans with disabilities are more similar to Neanderthals than those without deformities. All other fossil skulls were more similar to modern humans without disabilities.

“Our research may mean that we are one step closer to gaining a clear understanding of the causal chains that produce Chiari malformation type 1,” says Collard, co-author of the study. “Like other sciences, it is important in medicine to clarify the causal chain. A more clear causal relationship is about the chain of causal relationships that lead to a medical condition, and there is a greater likelihood that the condition can be managed or even resolved.”

Collard emphasized that these findings did not clearly demonstrate the association between this disorder and the Neanderthal gene. “Scientific research is rarely based on a single study, at the very least,” he pointed out.

Future work could potentially analyze more skulls, especially those of fossils, Corrado said. Researchers can also focus on collecting data from Africa. “What we know about the development of Neanderthal DNA in the gene pool of living humans suggests that we should expect a higher prevalence of Chiari malformation type 1 in Europe and Asia than in Africa,” Collard said.

If future research confirms the link between the Neanderthal gene and this disorder, “it makes sense to add screening for such genes to early childhood health assessments,” Collard said. This will allow individuals at an average risk of developing Chiari malformation type 1 to be identified and monitored and managed by a medical professional.

Scientists detailed their findings in the June 27 Journal of Evolution, Medicine and Public Health.

Neanderthal Quiz: How much do you know about our closest relatives?

Source link