Phage therapy manifests as a promising solution to antibiotic resistance by utilizing highly selective viruses targeting specific bacteria, but its effective deployment faces challenges associated with phage matching that match infection and regulatory considerations.

Antibacterial resistance (AMR) poses a serious threat to our ability to treat bacterial infections and is now one of the global threats to public health and economic development. Fighting AMR requires action to address the interrelationships of human, animal and environmental health, known in many areas as one health approach.

background

In 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) provided a harsh warning that “not only is there too little antibacterial agents in the pipeline, but also the time required for R&D and the possibility of failure, so is not enough innovation.” WHO also reviewed newly approved antibacterial agents that were released since 2017. Of the 13 newly approved antibiotics that have been approved, only two represent the new chemistry class. This clear lack of innovation identifies both the lack of a large pharma focus in this space and the scientific and technical challenges for discovering new antimicrobial agents that are effective against bacteria and safe for human use.

With new and innovative antibiotics available and the rapid increase in AMR, attention is being focused on bacteriophages (phages) as promising weapons against AMR.

Phage therapy as a weapon to fight AMR

Phages are viruses that have evolved to be highly selective in infected bacteria, often infecting only a small subset of certain bacterial strains, which is a subset of E. coli, a subset of bacterial species. This specificity for a very specific, limited set of bacteria is one of the greatest benefits of phage therapy and one of the biggest challenges to overcome. This specificity allows the phage to remove only harmful bacteria and not be affected by other beneficial bacteria. However, this means that phage therapy must be carefully matched to a particular bacteria, causing infection and/or the use of cocktails containing multiple different phages, each indicating the specificity of the target bacteria.

Phages are the most abundant organisms on the planet and are found in all natural environments. Phages play an important role in regulating bacterial populations and affecting microbial ecosystems. It is estimated that there are 1,031 phages around the world. This corresponds to one trillion phages present in all grains, equivalent to 200 million tonnes of biomass. As a result, each bacteria has multiple phages that can target it. One.

Roughly, there are two types of phage: lysis and lysis. Lysed phages follow the life cycle, rapidly replicating and rupture from cells, resulting in the death of bacterial cells as shown in Figure 1. In contrast, lysogenic phages do not replicate immediately. Instead, their genetic material is inserted into the host cell’s genome, creating what is known as prophecy. These prophages replicate when host cells grow, but can be triggered to lyse. It is important that only lytic phages are selected for therapeutic purposes and that phages with potential lysogenicity are excluded.

Phages – Possibilities and challenges

Combined with the coevolutionary nature of both phages and bacteria, phage abundance and diversity presents a unique challenge to the deployment and regulation of this class of treatments. In general, one of two options is available when considering phage therapy. 1) an impersonal phage cocktail containing preformed phages for a common infection, or 2) an individualized phage therapy performed in response to a particular infection of an individual.

A recent review of 100 human phage therapy treatments revealed that using personalized phage therapy was more effective than depersonalisation, especially when used in conjunction with antibiotics. After repeated hospitalizations, the patient received two weeks of phage therapy to effectively treat the infection.

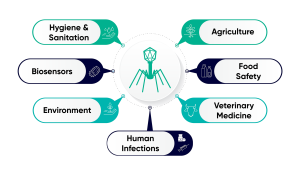

In addition to human health, phages have applications in other industries, from veterinary medicine to hygiene and hygiene (Figure 2). In these areas, a more general approach is for tissues to prepare a cocktail of multiple phages to provide broader efficacy for the target strain or strain. One such example is the “Bafasal +G®” poultry feed additive produced by Proteon Pharmaceuticals SA.

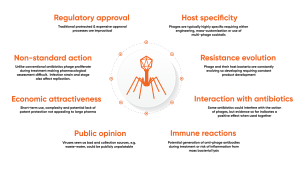

Phage therapy and treatment provide great promise to improve the health of humans, animals and crops. However, the widespread adoption of phage therapy is not yet a reality and requires input from a large number of stakeholders across the industry, from regulatory agencies to biopharmaceutical companies and technology providers. The unique and complex nature of the phage host interactions outlined in Figure 3, other biological and social factors, all illustrate challenges.

Despite these challenges, the industry has witnessed a significant increase in the number of successful use cases in clinical settings, the prophylactic use of phages in agricultural settings, and the development of hygienic materials phages contain. This growing interest in phage-based technologies is reflected in the increased production requirements and process control, requiring a transition from small-scale flask-based cultures to bioreactor-based approaches.

Increased production scale poses challenges as phage particles are broad and extremely difficult to remove from the surface. Phage persistence requires bioprocess scientists to employ complex and expensive molecular biology-based methods to validate the washing process to prevent cross-contamination between batches. In addition to complex cleaning verification, reusable bioreactors require long energy-intensive delegation/re-delegation cycles between production batches. Such delays and costs are discordant with the production needs of phage therapy, and should respond quickly to immediate needs and be as cost-effective as possible.

To this end, Cellexus Cellmaker bioreactors are rapidly established as the best bioreactor for tissues considering expanding phage production.

Cell Manufacturer: A reliable bioreactor for phage production

Cell makers allow phages to be produced in greater volumes at less cost and less time than previously possible.

Eliminate cleaning

CellMaker employs a single-use bioreactor bag, removing the need for expensive cleaning and verification procedures required when using traditional bioreactors. Regulatory support manufactured in ISO13485 and FDA 21 CFR 820 is available

Maximizes system uptime

By removing the need for long and expensive cleaning, decommissioning, and recommended steps, you are ready to go again within minutes. Simply put it in a new bag and fill it with media and the system is ready to use. When facilities actually disable downtime, they maximize production capacity, increase team productivity and are always ready to meet their needs.

Can change the amount of culture quickly

CellMaker Systems is “plug and play” and quickly replaces the enclosure and scales culture volumes from 1.5 liters to 50 liters using the same cell maker controller. The dual controller expands this further by being able to control two enclosures independently, providing production capabilities from 100 to 100 liters with 1.5 liters to 100 liters with one controller

Increased phage yield

Cellmaker utilizes fine bubble curtains to achieve both mixing and gas exchange, known as air-fuel mixing, which has been shown to produce significantly higher phages (10-100 times) than other methods. Higher concentrations allow for lower culture volumes, further reducing production time and costs, and positively affecting downstream treatments.

Versatility

It is an enclosed, disposable system that allows for a wide range of cell types to be cultured in aerobic or anaerobic states, allowing cell manufacturers to produce a variety of products and use them in a variety of culture processes.

Cellexus is committed to supporting phage scientists and developing solutions that meet evolving needs across sectors and regions. If you would like to discuss how you can help with your workflow, please contact us.

reference

WHO Website Browning, D. (2025). Bacteriophage: Translation into clinical practice. Industrial Pharmacy 74, 6-10. Chevallereaau, A., Pons, B.J., Van Houte, S. et al. (2022). Interactions between bacteria and phage communities in the natural environment. Nat Rev Microbiol 20, 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41579-021-00602-Y Pinay, JP. , Djebara, S., Steurs, G. et al. Results of individual bacteriophage therapy for 100 consecutive cases: a multicenter, multinational, retrospective observational study. Nat Microbiol 9, 1434–1453 (2024). The Straits Times Proteon Pharmaceuticals SA Website

This article will also be featured in the 22nd edition of Quarterly Publication.

Source link