Our understanding of how our species evolved has improved dramatically since we began analyzing ancient DNA. This year, researchers made impressive discoveries spanning 3 million years of human evolution, most of which relied on DNA, genome, or proteomic analyses.

Here are 10 major discoveries about human ancestors and ancient relatives that scientists will announce in 2025.

1. Two new species closely related to humans have been discovered in Ethiopia.

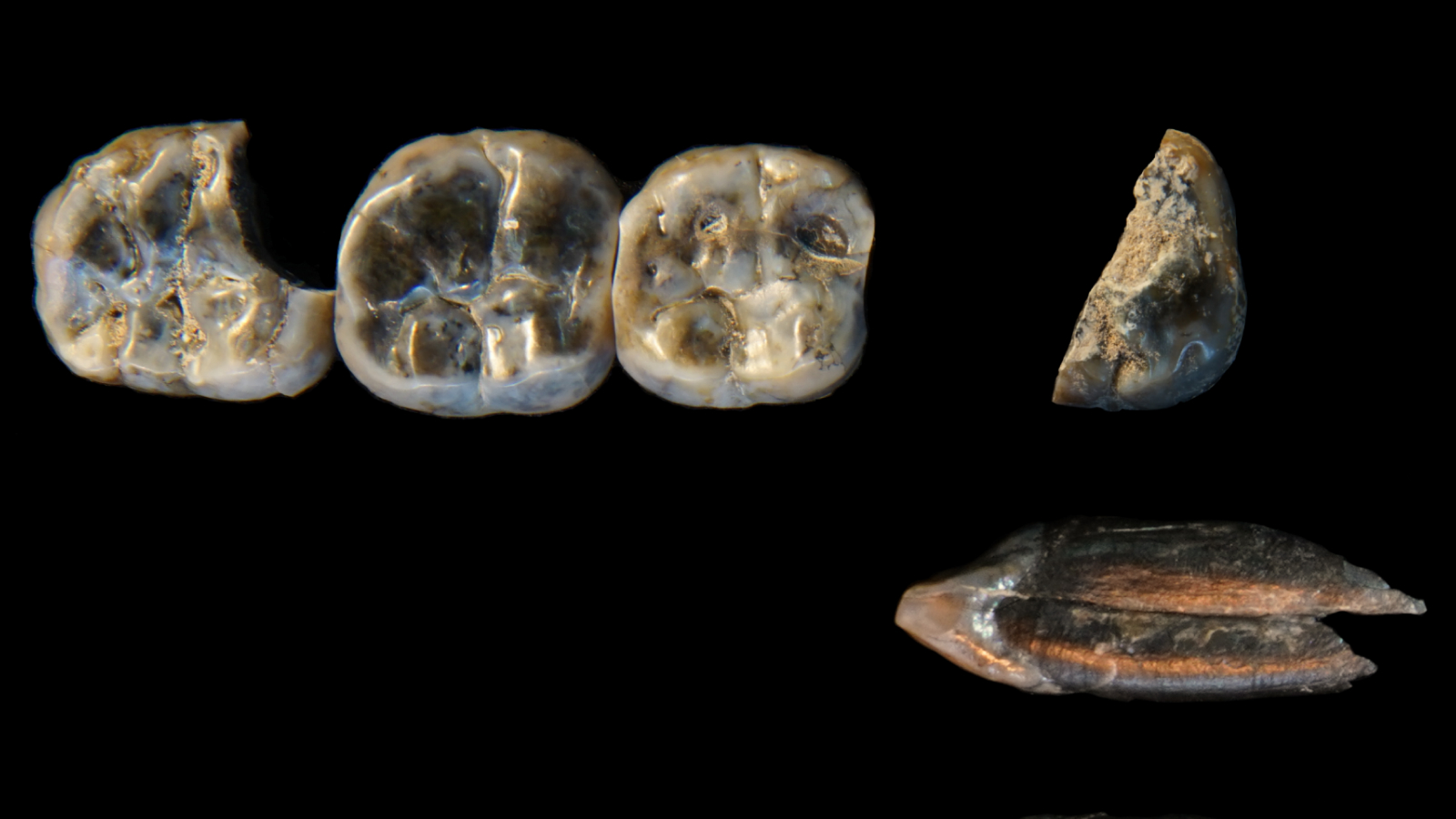

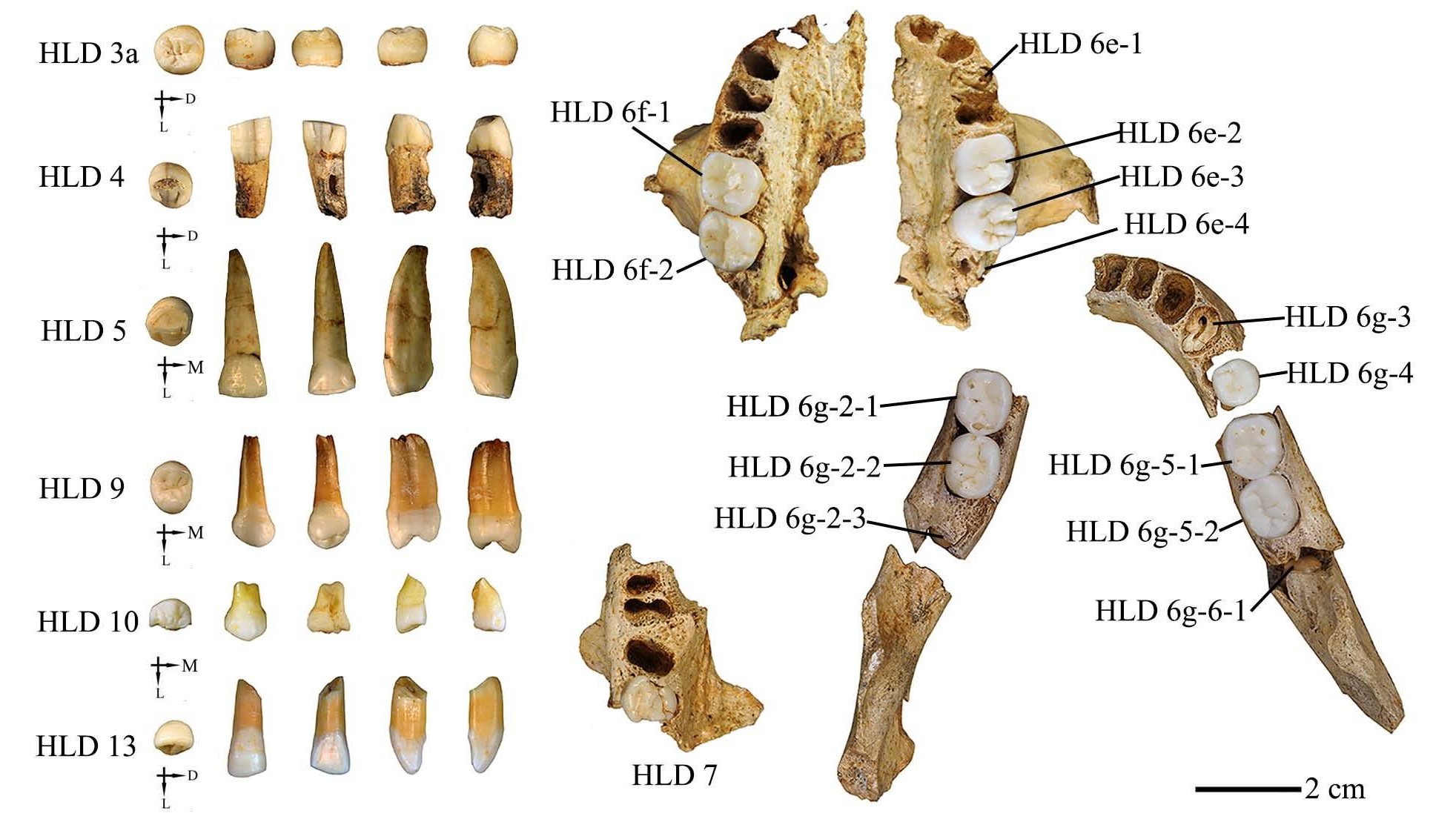

A small number of teeth found at the Lady Gerar site in Ethiopia suggest that a variety of previously unseen human relatives roamed the region 2.6 million years ago.

you may like

In August, researchers announced they had discovered 13 teeth. The 10 specimens are estimated to be 2.63 million years old and do not belong to either Australopithecus afarensis or Australopithecus garhi, the two known species of the genus Australopithecus from the region. The tooth has no unique features and is not found in the skull, so the newly discovered species from which it may have come does not have an official name. Researchers call it Lady Geral Australopithecus.

In the same study, researchers discovered two teeth that were 2.59 million years old and one tooth that was 2.78 million years old. They all appear to belong to the genus Homo, which would make them some of the earliest remains of our own genus.

The discovery of the teeth means that at least three ancient human relatives lived in this region of Ethiopia about 2.5 million years ago.

Hundreds of stone tools discovered in Kenya reveal that our ancient relatives had more advanced plans for the future 600,000 years ago than experts previously thought.

In a study in August, researchers examined more than 400 stone tools from the Nyayanga site dating from 3 million to 2.6 million years ago. This tool was probably not made by our genus. The tools were fairly basic, flakes carved from large stones, but the stones used to make them came from more than 6 miles (9.7 km) away.

The fact that hominins transported stones from great distances to make tools suggests a remarkable ability to plan ahead, long before the genus Homo.

3. Earliest evidence of Homo erectus found in Georgia

In July, researchers announced the discovery of a 1.8-million-year-old Homo erectus jawbone at the Orozmani site in the Republic of Georgia. In 2022, paleoanthropologists discovered a tooth believed to belong to Homo erectus, and a jawbone discovered this year confirmed the identity.

you may like

H. erectus is our direct ancestor and evolved in Africa about 2 million years ago. It was also the first human ancestor to leave Africa and eventually reach parts of Europe, Asia, and Oceania.

To date, the earliest evidence of Homo erectus outside of Africa comes from Orozmani and a second site called Dmanisi in Georgia, suggesting that our ancestors quickly left Africa and settled in the Caucasus region.

4. Mysterious humans arrived in Indonesia 1.5 million years ago.

Stone tools discovered this year on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi suggest that Homo erectus or an unknown human relative arrived in Oceania about 1.5 million years ago. This fits well with previous evidence that Homo erectus arrived on Java about 1.6 million years ago.

But researchers aren’t sure whether the toolmakers were really Homo erectus, as no ancient human bones have yet been found on Sulawesi. Another candidate may be H. floresiensis, a small “hobbit” species found on the neighboring island of Flores. Some researchers believe that hobbits originally came from the island of Sulawesi.

Further excavations on Sulawesi may eventually reveal which species lived on the island.

5. Humans arrived in Australia 60,000 years ago.

Genetic research published in November showed that Homo sapiens likely reached Australia 60,000 years ago via two different routes through the western Pacific Ocean. The discovery appears to settle a long-standing debate about humans reaching the continent, a feat that required watercraft and navigational expertise.

The new DNA evidence supports a “long chronology” of archaeological evidence, including stone tools and pigments on cave walls, that the first arrivals appeared around 60,000 to 65,000 years ago.

But not everyone is convinced. In a July study, researchers used the fact that some indigenous Australians have Neanderthal DNA to suggest that Australia was not settled until about 50,000 years ago, an idea known as the “short chronology.”

Further research into the origins of the earliest Australians will take place in the future.

6. Drought may have doomed the Hobbits.

By 50,000 years ago, H. floresiensis appears to have disappeared from Flores Island. In December, researchers published a study suggesting that drought may have accelerated their demise.

Scientists studying rainfall on the island of Flores have found that between about 76,000 and 61,000 years ago, rainfall decreased significantly, and the population of a species of elephant called the stegodon hunted by the Hobbits disappeared about 50,000 years ago.

Researchers believe that reduced rainfall has caused the Stegodon population to decline, making life more difficult for the hobbits. And if modern humans also reached Flores (perhaps part of the wave of people who eventually settled in Australia), competitive pressure from another species might have wiped out H. floresiensis.

7. Denisovans had faces.

Our extinct relatives, the Denisovans, were first discovered in 2010 based on DNA extracted from tiny finger bones. But until this year, no one knew what Denisovan skulls looked like.

Researchers have debated for years what species this thick jawbone, discovered off the coast of Taiwan in 2000, belonged to, with some suggesting Homo erectus and others Homo sapiens. But in May, researchers announced using paleoproteomic analysis that the jawbone belonged to a Denisovan man.

In June, an ancient protein revealed that a skull called “Dragon Man” discovered in China in 1933 belonged to a Denisovan, finally giving its name. However, although dragonmen are now part of the story of human evolution, it is not yet clear whether this group should be considered a separate species, Homolongi.

And in September, researchers reconstructed a million-year-old crushed skull from China, suggesting it may have been the ancestor of Denisovans, rather than Homo erectus.

These three discoveries offer paleoanthropologists clues about the origins and spread of the mysterious Denisovans. This challenge will certainly continue for years to come.

8. Denisovan DNA helped Native Americans survive.

Researchers announced in August that some people with Native American ancestry carry Denisovan genes, which were likely passed on through Neanderthals who interbred with modern humans.

By examining a gene that codes for a protein called MUC19, scientists found that one in three Mexicans living today has a gene similar to that of Denisovans, which they likely “snipped over” from Neanderthals. Basically, Neanderthals acquired the gene by interbreeding with Denisovans and passed it on when interbreeding with humans. This is the first time scientists have discovered Denisovan genes in humans that came via Neanderthals.

Although it is currently unknown what exactly the Denisovan variant of the MUC19 gene does, researchers believe that its conserved presence in the human genome must have been beneficial to early Americans.

9. Interbreeding was rampant among our ancient relatives.

Since the genomic revolution, the story of human evolution has become astonishingly confusing. DNA and protein analysis has revealed new groups such as Denisovans and interbreeding between Neanderthals, modern humans, and Denisovans. But this year also produced some surprising combinations.

In August, researchers announced that several 300,000-year-old teeth suggest humans and Homo erectus may have interbred in China. The tooth has an unusual combination of ancient features, such as thick molar roots, and modern features, such as small wisdom teeth, which could mean the two different species share genes.

Researchers announced in March that Neanderthals, modern humans, and a mysterious third lineage coexisted with each other in caves in what is now Israel about 130,000 years ago. Homo groups may have been mixing and intermingling for 50,000 years, sharing cultural practices in addition to genetic material.

And in November, DNA research into the arrival of humans in Australia suggested that these early human settlers likely interbred with one or more archaic hominin groups, such as H. longii, Homo luzonensis, or H. floresiensis, along the way.

21st century technology allows us to see genetic differences between these groups, but perhaps our earliest ancestors simply saw Neanderthals, Denisovans, and others as the same human race.

10. Most Europeans had dark skin until 3,000 years ago.

In a study published in July, scientists found that genes for lighter skin, lighter hair, and lighter eyes emerged among Europeans only about 14,000 years ago, and that until 3,000 years ago, most Europeans had dark skin, hair, and eyes.

Researchers identified this in 348 ancient DNA samples taken from archaeological sites across Western Europe and Asia. The first humans to arrive in Europe about 50,000 years ago had genes for dark skin. Once mild traits emerged, they appeared only sporadically in the genetic data until very recently. By around 1000 BC, these lighter features had spread to Europe.

However, it is still unclear whether having bright skin, hair, and eyes conferred any evolutionary advantage on early Europeans.

Source link