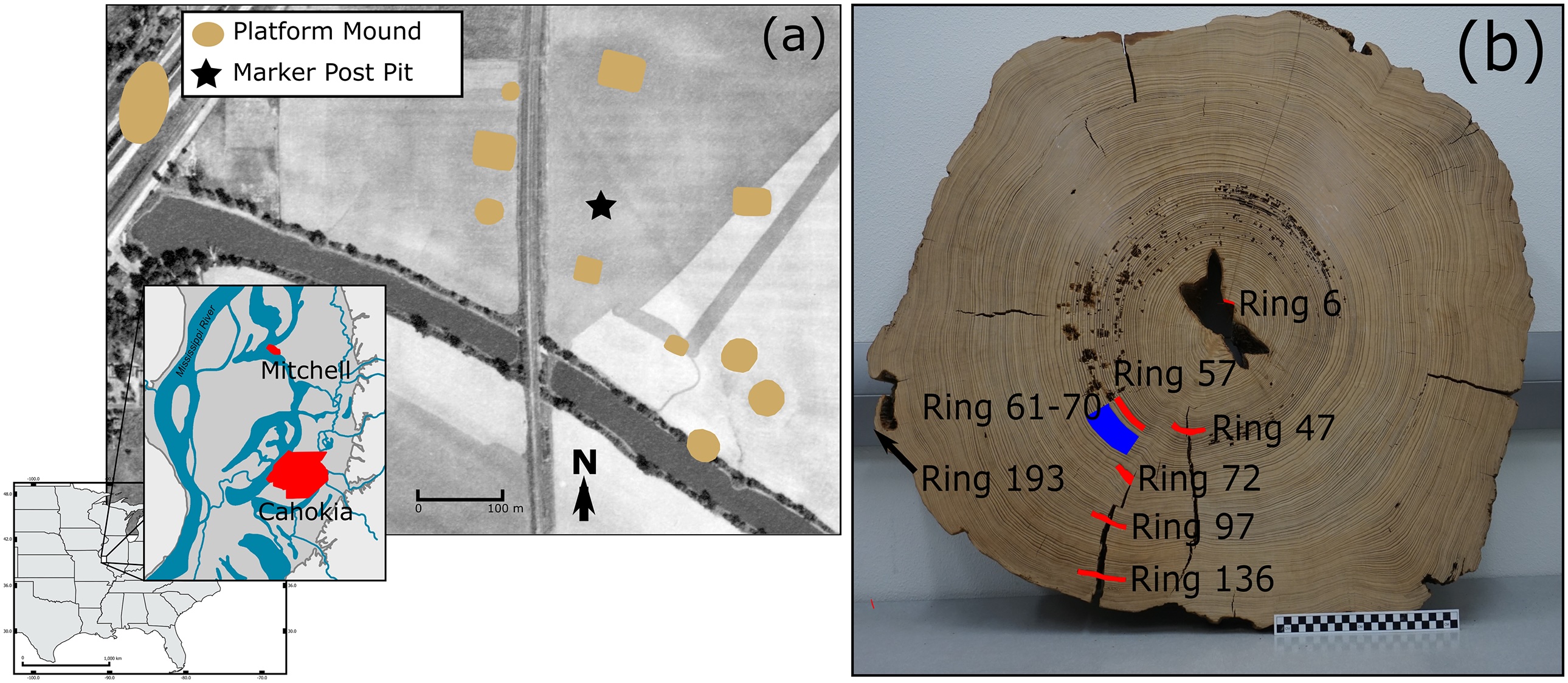

About 900 years ago, the Native American tribes of Cahokia, the largest pre-Columbian city in northern Mexico until colonial times, cut down giant trees and transported them more than 110 miles (180 km) to use as monument markers, a new study finds.

The tree, known as the Mitchell Log, is the largest sign of its kind in what is now known as Cahokia, an earth mound in southwestern Illinois.

you may like

By determining the exact dates when the Mitchell logs were erected and removed, the researchers behind a new study published Oct. 3 in the journal PLOS One have created the most accurate timeline yet of Cahokia’s rise to power and subsequent decline. Additionally, by determining where the poles came from, the researchers raised new questions about the transport of thousands of similar poles during the peak of Cahokia’s influence.

big city

The city of Cahokia had a population of up to 20,000 at its peak between 1050 and 1200.

“Cahokia grew rapidly in the late 11th century, with immigrants accounting for one-third of the population, and reached its peak in the mid-12th century when Cahokia goods, people, and ideas reached from the Gulf Coast to the Great Plains,” said study lead author Nicholas Kessler, assistant professor at the University of Arizona Tree Ring Research Institute, and study co-author Erin Benson, an Eastern anthropologist. forest archaeologists at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign told Live Science via email.

During this period, the Cahokians built large monumental structures called beacon columns. These pillars were hewn from the trunks of giant trees and were usually placed near communal courtyards, atop pyramid mounds, and within prominent buildings.

“In the pre-contact Cahokian world, poles were often placed in special locations (plazas, mounds, temples) where they served as pivots, physically linking the upper, middle, and lower worlds and helping to mediate their powers and people’s relationships with them,” Kessler and Benson said.

However, by 1200, Cahokia’s political, social, and economic influence had waned, and marker posts were no longer erected.

To better understand the Mitchell Log’s timeline and origins, the team radiocarbon-dated the post and investigated its provenance. They did this by looking at the ratio of strontium isotopes, atoms of the element strontium, which have different numbers of neutrons in their nuclei. Strontium occurs naturally in rock and has unique isotopic signatures depending on its location. This imprint acts like a fingerprint, with slight differences, and is passed on to the water and the plants that grow on it. By studying the features found in animals and plants, researchers can determine which bedrock they originally came from.

you may like

Scientists have discovered that the logs, which once stood 59 feet (18 meters) tall and weighed 4.4 to 5.5 tons (4 to 5 tons), were likely sourced from more than 110 miles from southern Illinois.

Kessler and Benson say the Cahokia people likely floated the logs upstream or transported them on rafts. “Alternatively, it could simply have been transported overland, via trails and roads that reliably connected Cahokia to surrounding communities,” the authors said.

With the help of cosmic events recorded in the tree’s growth rings, the felling of the tree was determined to be in 1124, coinciding with the city’s heyday. These cosmic phenomena are characterized by sudden spikes in cosmic radiation, especially radiocarbon, usually caused by solar storms or supernovae. Trees grow one ring each year, which stores radioactive carbon, so sudden spikes like this are recorded in the rings and can be used to pinpoint a particular calendar year.

Assuming the Mitchell log stood for one or two generations before natural decay set in and removal began, the marker likely stood between 1150 and 1175. This period coincides with the time when nearby ceremonial centers were being abandoned as Cahokia’s decline began, and provides greater insight into the timing of this event, the researchers said.

In the late 12th century, Cahokia experienced a variety of changes, including increased drought, changes in the types of exotic goods traded, changes in public space, and the construction of mounds, the researchers explained in their study.

Whether all of Cahokia’s marker posts were sampled during this time remains a question the authors hope to answer in future studies. In any case, the evidence shows that no new markers were erected at Cahokia by 1200. By 1400, the city was abandoned, but archaeologists still don’t know why.

Source link