One of the earliest known human burials, one of the burials of young children, may have been a cross between modern humans and Neanderthals, new research suggests.

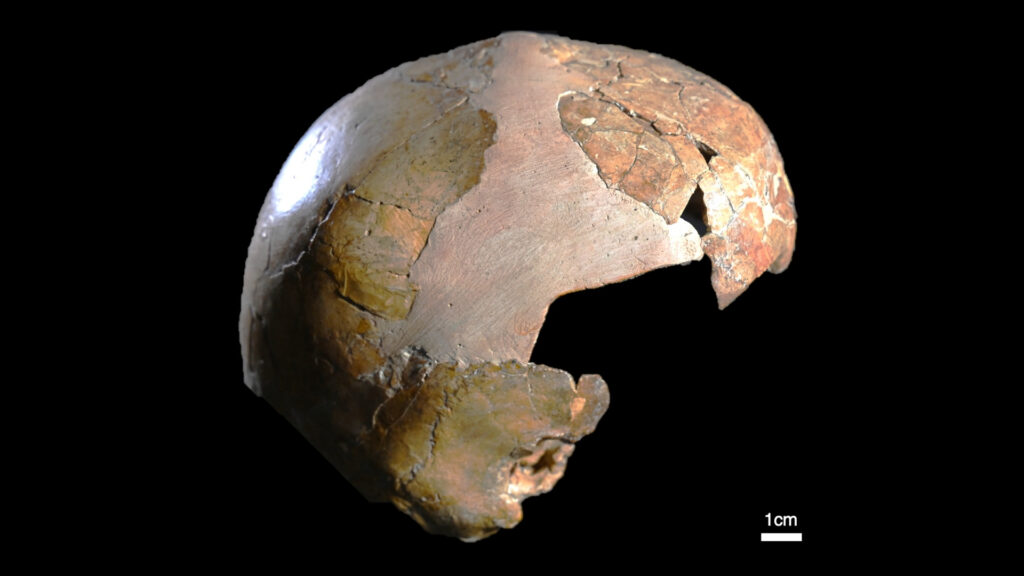

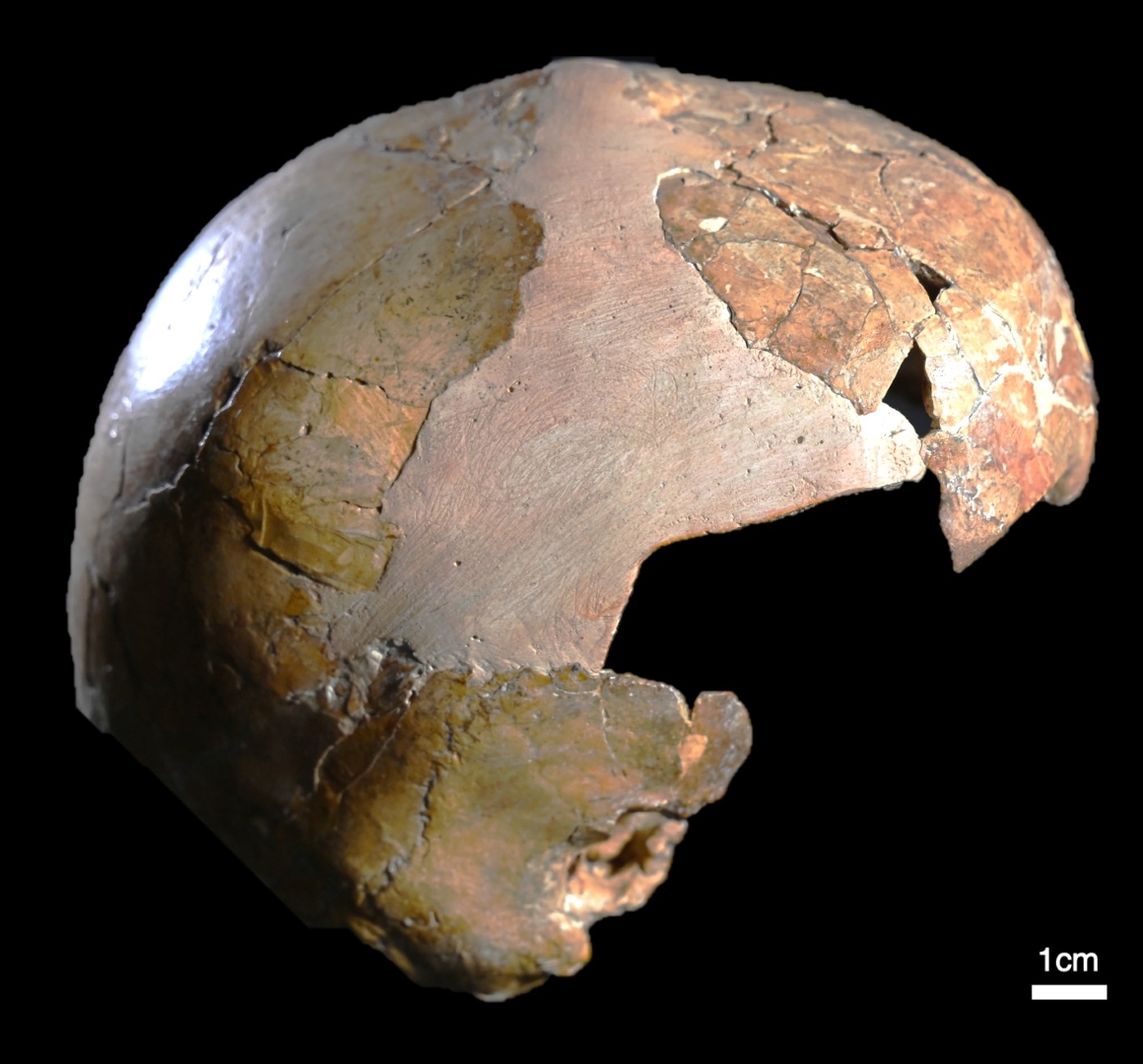

Researchers analyzed a skull found at a burial site 140,000 years ago and concluded that the child it belongs to has both modern human (Homo sapiens) and Neanderthal traits. However, the exact ancestor of a child is still uncertain.

The skull was part of a cache of mysterious human remains at Skhul Cave, Mount Carmel, Israel almost 100 years ago. These fossils have been the subject of many scientific debates since their discovery, but were primarily considered anatomically modern humans.

You might like it

Skhul Cave is the earliest of all known organized human burial sites, so the identity of the remains buried there is important. The authors of the study appeared in the July-August issue of Journal L’Anthropologie and based on their analysis, they argued that the bodies were no longer solely due to Homo Sapiens.

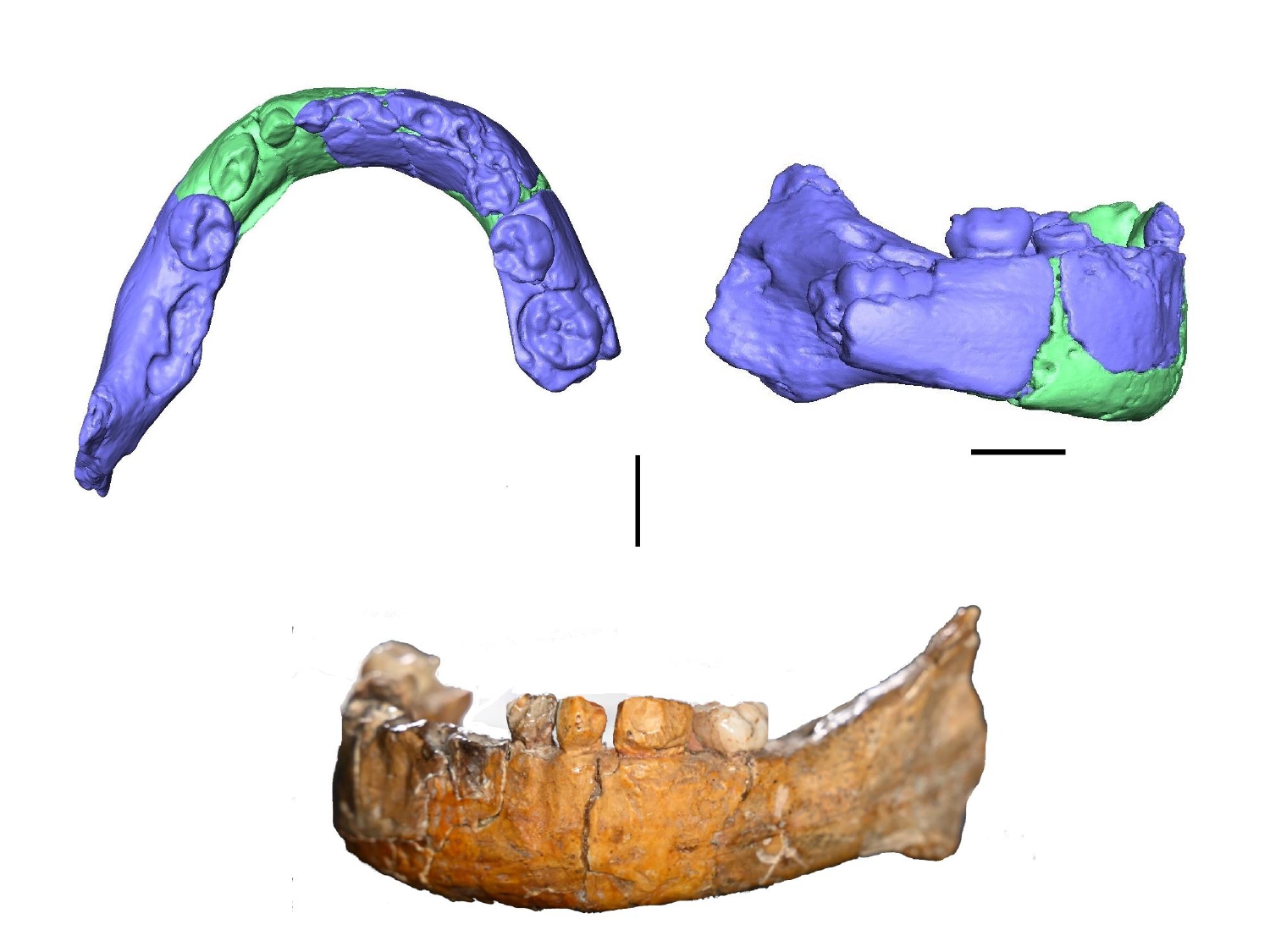

Researchers are using CT scanning techniques to see new details on the child’s skull (Skhul I), which consists of broken brain waves (neurosyndrosis) and jaw (mandibular). Further studies showed brain cases primarily typical of homo sapiens, but studies found that their jaws were Neanderthal-like.

Research co-author Anne Dambricelle Malasse is a paleontologist at the National Centre for Science Research (CNRS) in France, and the French National Museum of Natural History told Live Science via email that the morphology represents the variability of Homo sapiens, and that children are “objectively” hybrids.

However, not everyone thinks the findings are very conclusive. Chris Stringer, a paleontologist at the Museum of Natural History in London, said that although he was not involved in the study, the mandible looked primitive, he thought that, when all the fossils were considered together, he thought it was primarily in line with Homo sapiens. However, Stringer noted that the conclusions of this study are consistent with a 2024 study suggesting that there was a cross-population (or heterologous) gene flow between Neanderthals and humans about 100,000 years ago.

“Even if it’s not a first-generation hybrid, it’s certainly possible that Skhul fossils reflect the flow of genes between the two populations,” Stringer said in an email. “Overall, looking at all the materials, including skeletons, this material is still in my opinion, primarily homo sapiens.”

Related: “Hobbit”, Neanderthal, Reconstructing the stunning face of Homo Erectus

John Hawks, an anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who was not involved in the study, told the new scientist that the study was promoting understanding of the skull, but scientists couldn’t clearly identify children as hybrids without extracting their DNA.

“Human populations vary and there could be a lot of variation in appearance and physical shape without being mixed with ancient groups like the Neanderthals,” Hawks said.

Modern humans, raised by Neanderthals, are the reasons why most people living today carry 1% to 3% of the Neanderthal DNA. However, there is much to learn about this interconfusion and how ancient human family trees are perfect.

Who was this ancient child?

Archaeologists first discovered human remains at Skhul Cave in 1928. The excavation revealed the skeletal structures of seven adults and three children. Bones were initially considered to be a transitional species between Neanderthals and modern humans. The researchers later suggested that it was a hybrid between the two, but the assessment was also rejected, and the study found that they were anatomically classified as modern humans.

Skhul I belonged to a child between 3 and 5 years old, probably a woman. The centre section and most of the base of the skull face were missing, but the rest were dismembered. In the past, archaeologists have tried to restore the skull and integrate fragments with plaster, making it even more difficult for modern researchers to study. A new CT scan allowed researchers to effectively remove the plaster and compare the skull with other specimens.

Modern human features of the skull include the vertical orientation of the bones on the sides of the skull base, while Neanderthal-like features of the jaw include a lack of jaw.

Source link