The major Atlantic currents, which appear to be slowing down due to climate change, may be more resilient to global warming than scientists previously thought. New research shows thanks to a secret backup system.

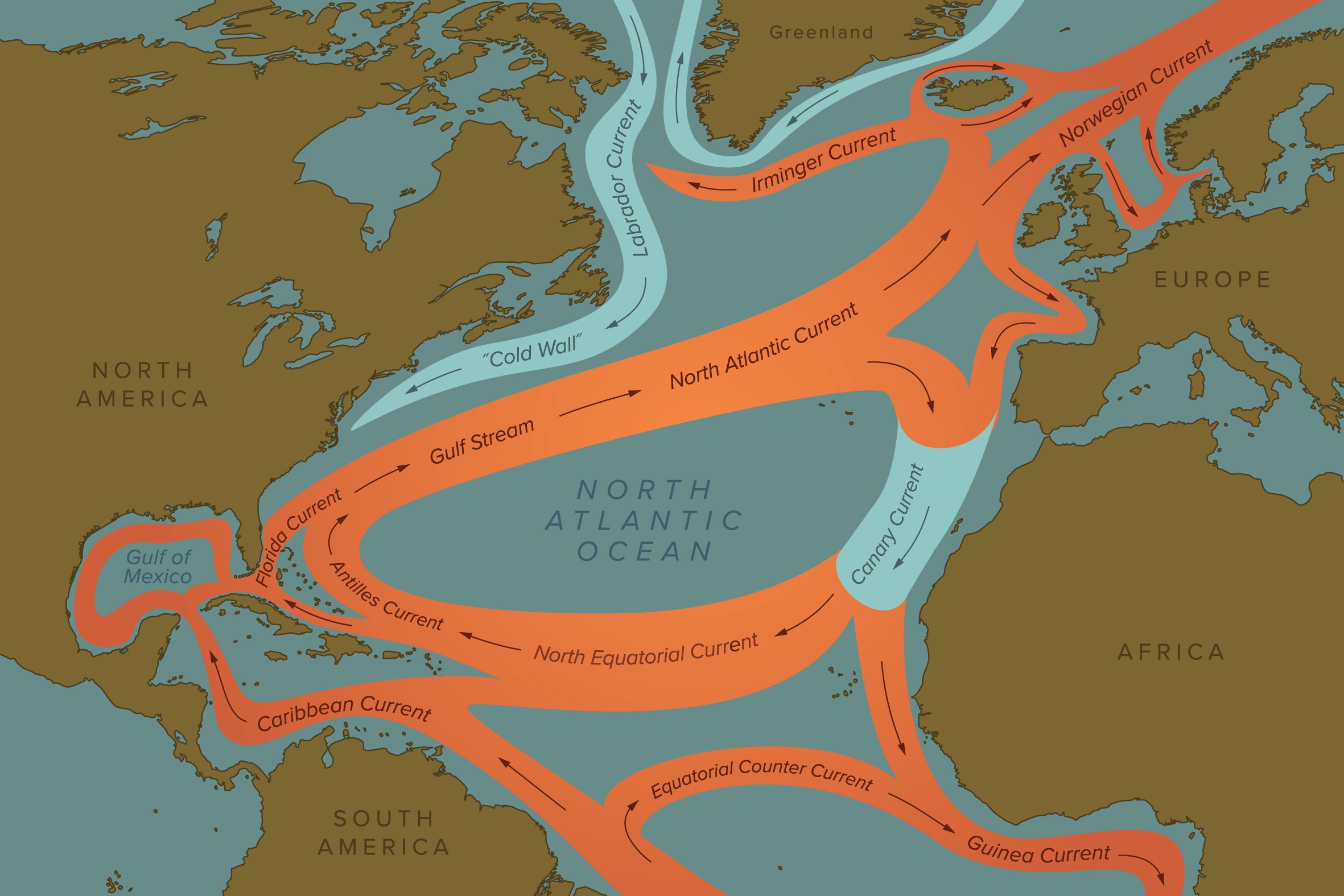

The Atlantic Meridian Surrounding Circulation (AMOC) is a network of currents that loop around the Atlantic Ocean like a giant conveyor belt. The cold, salty waters sink near Greenland and move south along the seabed. Eventually these waters rise back to the surface near the Antarctic, returning north, bringing the Balmier waters to the northern hemisphere. This system is particularly important for warming Europe.

In recent years, experts have repeatedly ring the alarm bell, suggesting a step to completely shut down the watersink, which could lead to a significant drop in temperatures in Northern Europe and exacerbate sea level rise along the US East Coast.

You might like it

Researchers believe this important stage of AMOC is problematic due to the changing formation of dense water, a process in which the top layer of the ocean cascades to the bottom. Cold, salty water is more dense than warm, salty water. Under normal conditions, surface water loses much heat as it travels through the North Atlantic and sinks when it reaches the end of its northbound journey.

This usually takes place in the Nordic seas (Greenland, Norway and Icelandic seas), a physical oceanographer at the University of Bergen at the University of Norway and the lead author of the new study, and was emailed to Live Science.

However, as climate change cooks the planets, the surface waters in the region have not transferred much heat to the air, but the Meltwater rivers also erupt into the ocean from the Arctic and Greenland ice sheets, diluting the salinity of the surface waters and preventing them from sinking.

Related: The Atlantic Current is much faster and weaker than scientists predicted

Since 1993, dense aquatic layers in Scandinavian oceans have been decreasing, writing about problems throughout the Atlantic circulation system. If there is no newly discovered backup system, Årthun said. Researchers published their findings in the journal Science Advances on Friday (July 11th).

“Porporateization” of the Arctic Circle

For this study, Årthun and his colleagues supplied computer models with density measurements from the North Atlantic, Nordic seas and the Arctic ocean. They compared the results with available observations to ensure that simulations in this region accurately reflected the process.

This simulation confirmed that the Arctic Ocean undergoes a process known as “total degree.”

“The governor refers to the Arctic Ocean’s transition from a cold, ice-covered state to a warmer, more ice-free state,” Årthun said.

In recent decades, sea ice has been seen in the Barents Sea, an Arctic region between Scandinavia and Svalbad. “We expect the Barents Sea to be the first ice-free Arctic region,” he said, adding that Atlantic Waters also extends to the Eurasian Basin, north of the Barents Sea.

Aging in the Arctic Ocean means that the area produces more dense water than before, Årthun said.

“I see this decreases [in dense water formation] In Nordic waters, they are compensated by the formation of dense waters north of the Barents Sea and Svalbad,” he said. […]therefore, it increases the area where dense water can be produced. ”

The author believes this backup system will help maintain AMOC. “There’s a process that adds resilience to AMOC and it’s probably going to cause serious weakening or collapse,” Årthun said.

Further research is needed to understand whether this backup system will continue in the global warming world. There are also questions about how well the Arctic Ocean can replace Nordic oceans by forming extremely dense waters, said Nicholas Fuchal, a physical oceanographer and assistant professor at the University of Georgia, was not involved in the study.

Foukal told Live Science that it would be interesting to explore whether the dense water still formed because “the masses of water that historically formed in the Greenland Sea were very dense.”

The Greenland Sea is a very deep ocean basin that is exposed to frigid gusts of wind from the Greenland ice sheet. “There’s no setting of this kind in the Arctic,” Fukal said. “I doubt these really dense waters are forming in the Arctic.”

Source link