A recent publication of the University of Edinburgh’s Race and History Reviews focuses on the “Cannel Room,” a collection of 1,500 human skulls sourced for research in the 19th century.

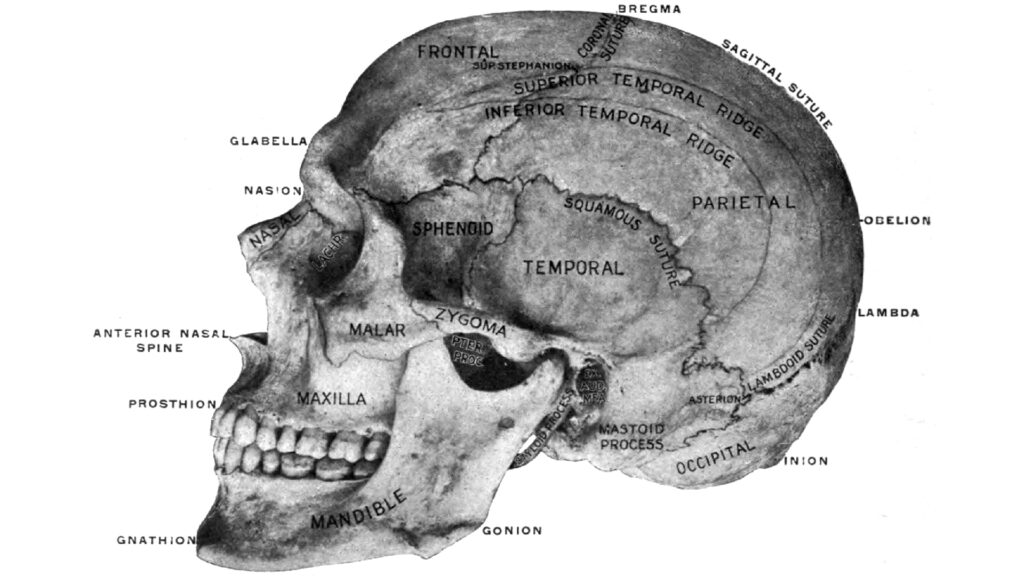

Cranial measurement, a study of skull measurements, was widely taught in medical schools in the UK, Europe and the US from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Today, the harmful and racist foundations of cranial measurements are trusted. Head size and shape have long been proven to be unrelated to the mental and behavioral characteristics of an individual or group.

You might like it

However, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, thousands of skulls gathered to enable research and guidance on scientific racism. The Skull Room in Edinburgh is by no means unique.

Unlike the pleura, a general theory that links personality traits to head collisions, cranial measurements revolved around data collection and statistics, which allowed them to enjoy extensive scientific support in the 19th century.

Related: What is the difference between race and ethnicity?

Craniometricists measured skulls and averaged results from different population groups. This data was used to classify people into races based on head size and shape. Cranial measurement evidence was used to explain why some people seem to have become more civilized and evolved than others.

The enormous accumulation of data drawn from the skull appealed to Victorian scientists who believed in the objectivity of numbers. It was equally useful in examining racial bias by suggesting that differences between people were innately biologically determined.

Medical history

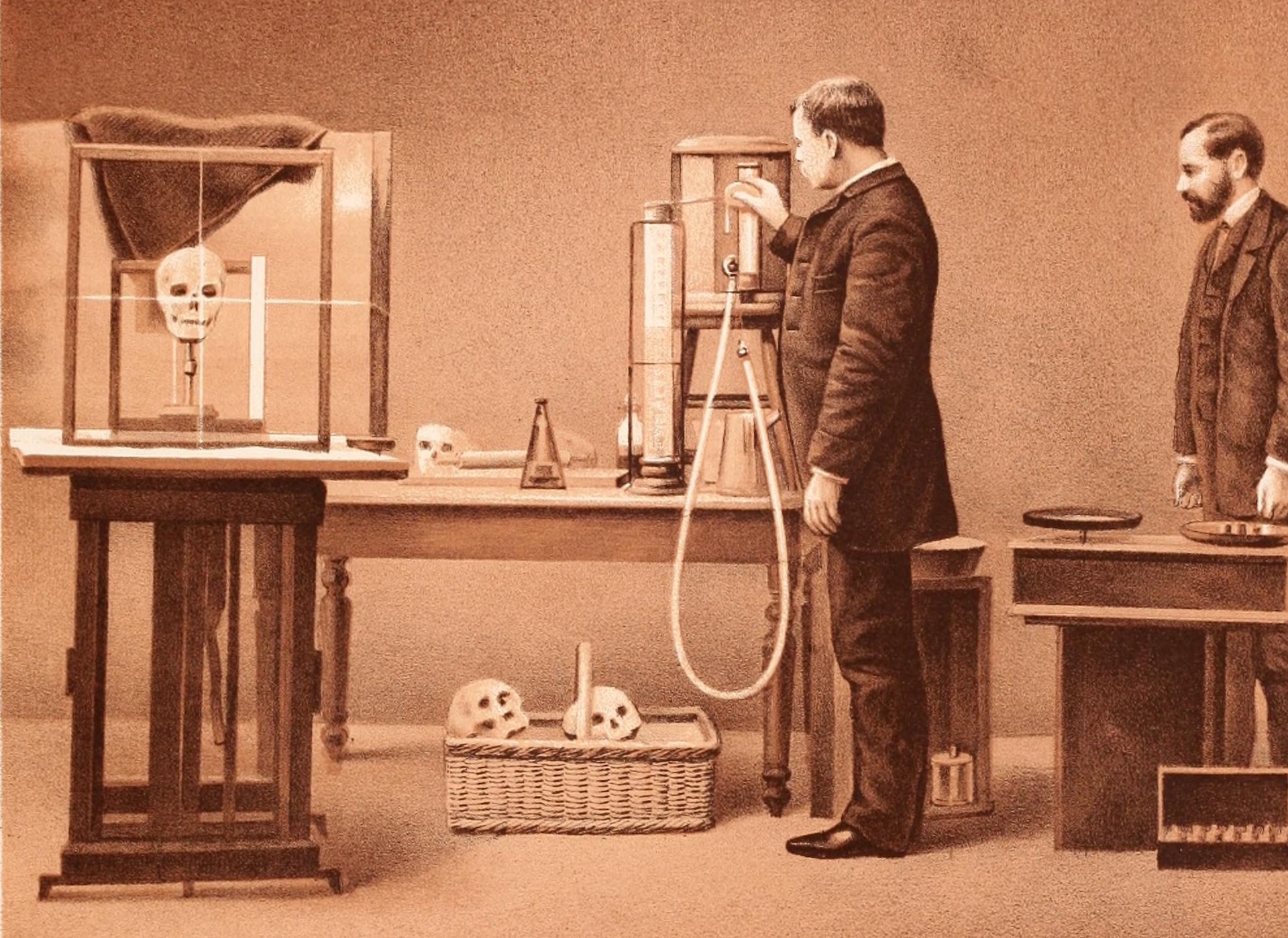

Skull studies were central to the development of anthropology in the 19th century. However, before anthropology was taught at British universities, markers of racism were studied by anatomists who were skilled in identifying tiny differences in skeletons. Skull research entered the university curriculum through medical schools, particularly the school of anatomy.

For example, when Alexander McAllister was appointed professor of anatomy in Cambridge in 1884, some of his first lectures were in “Types of Human Skulls.”

McAllister’s 1892 annual report at the Cambridge University Reporter explains how Cambridge skull strains were increased from 55 to 1,402 specimens. In 1899 he reported donations of more than 1,000 ancient Egyptian skulls from the archaeologist Flinderspetry. Much of Macalister’s skull collection is founded in the Duckworth Laboratory, a university founded in 1945.

As craniometric research gained fame, institutions had to compete for cranial collections when they came onto the market. Statistical accuracy relied on a vast set of cranium measured to produce representative “types.” This has resulted in an increase in demand for human remains.

In 1880, the Royal College of Surjeans purchased 1,539 skulls from Joseph Bernard Davis’ private collection. It was added to the existing cache of 1,018 skulls, creating the UK’s largest skull collection. This collection was largely destroyed in 1941, when university buildings were bombed during World War II. The remaining skulls are no longer held by the Royal College of Surjeans.

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History contained a row of Krania in anatomical exhibitions in the 19th century, as well as the University of Manchester School of Medicine (the School of Medicine is no longer on the same site). This investment in skulls ensured that race researchers have sufficient material for research and use in education.

The catalogs held by universities from the 19th and early 20th centuries reveal not only the size of the skull collection, but also the origins of individual specimens.

Historical trauma

Some medical schools, such as Edinburgh, reused skulls sourced by thoracic society at the beginning of the century to strengthen their holdings. Others, including Oxford, used skulls excavated by archaeologists to conduct racial studies of the country’s past. This study sought to track the movements of Celtic, Norman, Saxon and Scandinavians across the British Isles.

However, skulls from abroad were particularly respected because crannies wanted to capture the full extent of racial variation. A medical alumni from a British university posted to the colony sent foreign bones to an old professor.

My future book study on Skull Collections found that the Cambridge skull register contains skulls sent by former students stationed in India. He picked it from the Bombay crematorium despite the rage of the mourners who gathered. Embracing brave graves and colonial violence was central to the international network that provided the skull room of British universities.

The racist ideology that spurred the skull collection 150 years ago has been fully trusted. However, some anthropologists believe that these bones could still shed light on human origin, relationships and movement.

However, ethical factors now form equally institutional policies for human remains. The Pit Rivers Museum in Oxford displayed the infamous “Shrinked Head” in 2020.

Increasingly, universities and museums have faced historical injustice and intergenerational trauma that has been perpetuated by the maintenance of human remains. Since the 1970s, indigenous groups around the world have launched campaigns to repatriate their ancestor bones. Research institutions are becoming increasingly sensitive to these requirements.

In London, the Royal Surgeons Museum no longer displays the skeletons of Charles Byrne, the so-called “Irish giant.” Byrne had expressly denied his consent that his body would be dissected and mounted before he died in 1783.

The skulls of British universities are evidence of the vast theft of human bodies from almost every territory on Earth. However, if their discriminatory history is recognized and corrected through their return, they could become a powerful symbol of reconciliation.

A spokesman for the Duckworth Institute at Cambridge University said:

“We, like many institutions in the UK, address the legacy and past unethical practices of gathering our collections of care, and through respect and equal partnerships, the Duckworth Collection is actively expanding in archived documents and essentially improving its databases.

This edited article will be republished from the conversation under a Creative Commons license. Please read the original article.

Source link