Protein-based qubits could be key to accelerating biological research at a minimal scale thanks to new scientific breakthroughs.

Researchers at the University of Chicago have discovered ways to turn fluorescent proteins into biological qubits that can be made directly within the cell, and use them as a way to detect magnetic and electrical signals within the cell. This breakthrough is explained in detail in a paper published in the Nature Journal on August 20th.

“Our findings not only enable new methods of quantum sensing within living systems, but also introduce a fundamentally different approach to the design of quantum materials,” Peter Maurer, co-investigator and assistant professor of molecular engineering at Uchicago, said in a statement. “Specifically, we are now able to begin using natural unique evolution and self-organizing tools to overcome some of the obstacles faced by current spin-based quantum technologies.”

You might like it

By developing biological qubits that can be deployed within cells using existing proteins already in use in microscopes, this study bypasses the need to modify existing quantum devices to operate in biological systems. This could ultimately lead to quantum sensors that do not require the extreme cooling and separation required for quantum technology.

Fluorescent findings

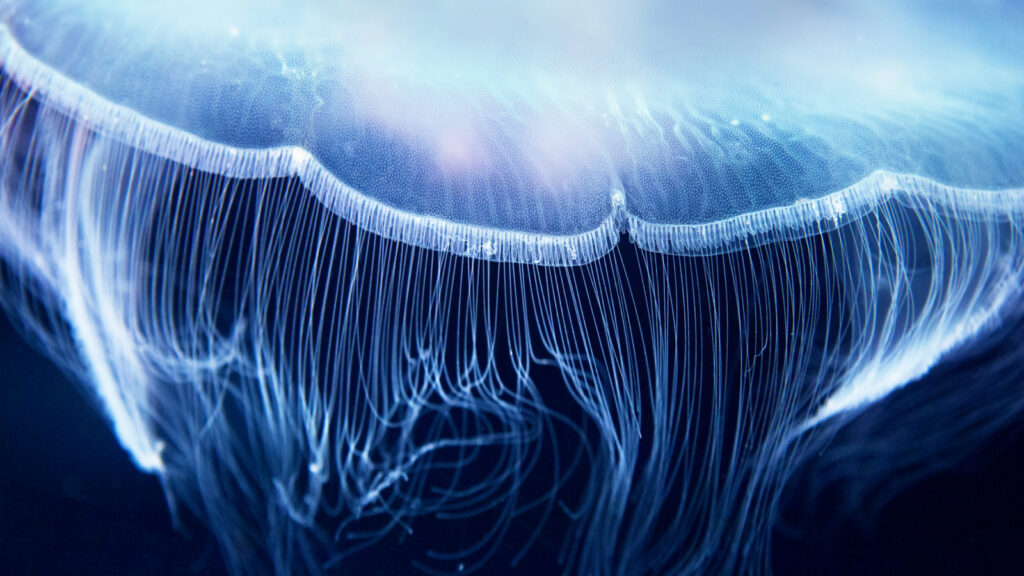

Fluorescent proteins found in various marine organisms absorb light at one wavelength and emit it at another. For example, this gives some jellyfish the ability to shine. Therefore, they are used by biologists and tagged cells via protein fusion via genetic codes.

Researchers have discovered that the fluorophores of these proteins, which allow light closure, can be used as qubits due to their ability to have a metastable triplet state. This is where the molecule absorbs light and transitions to an excited state with two highest energy electrons at parallel spins. This lasts for a short period of time before it becomes corrupted. In quantum mechanical terms, molecules superimpose multiple states at once until they are directly observed or destroyed by external interference.

Related: Small cryogenic devices reduce quantum computer heat emissions by 10,000 times and could be released in 2026

To capitalize on this, researchers have developed a custom confocal microscope, an optical system containing a series of lenses and mirrors that use laser light to generate high-resolution images of biological samples, addressing the spin state of enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) and used as a Qubit for purified protein.

Laser microscopy initially induced the spin state into the EYFP using a 488 nanometer light pulse. The near-infrared laser pulse then triggered readings of the triplet spin state with “up to 20% spin contrast.” In other words, researchers could see enough difference to use proteins as Qubit in their spin state as operating Qubit.

Once the spin was initialized, the researchers used microwaves to keep the spin coherent oscillations between the two levels. Therefore, the protein acted as qubits of approximately 16 microseconds before the triplet state collapsed.

You might like it

Biological breakthrough

Observe how electron pulses from when an electron hits the laser can use biological qubits as quantum sensors to pick up what is happening within the cell.

This could provide insight into biological functions at the nanoscale, including protein folding, tracking cell biochemical reactions, and monitoring how drugs bind to target cells and proteins, scientists said in their study. It could also lead to advances in medical imaging and early detection of disease pathways.

Biological qubits can shake up biological sensing and open up new ways to create quantum sensors, but there are still hurdles to overcome.

Effective manipulation of the spin state of fluorescent proteins required maintaining it at liquid nitrogen temperature. And although biological qubits proved to be effective in complex environments (most of the breakthrough) of mammalian cells, they had to be cooled to a temperature of 175 Kelvin (–98.15 degrees). At room temperature, the technique still works in bacterial cells, and researchers detect magnetic resonance optically, but only at a contrast of up to 8% there is a rapid depletion of the EYFP spin state.

The sensitivity of biological quantum sensors is lagging behind solid-state sensors, such as those made from diamond defects. So, before intracellular biological qubits and quantum sensors become practical tools for use in biology and medicine, there is still work to do about stability and sensitivity.

However, this is a breakthrough beyond the proof-of-concept stage, and encoding Qubit directly into a cell opens up new means of quantum technology where the boundaries between quantum physics and biology are blurred.

Source link