Three million years ago, today’s great penguins, the extinct relatives of the emperor and king, lived in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

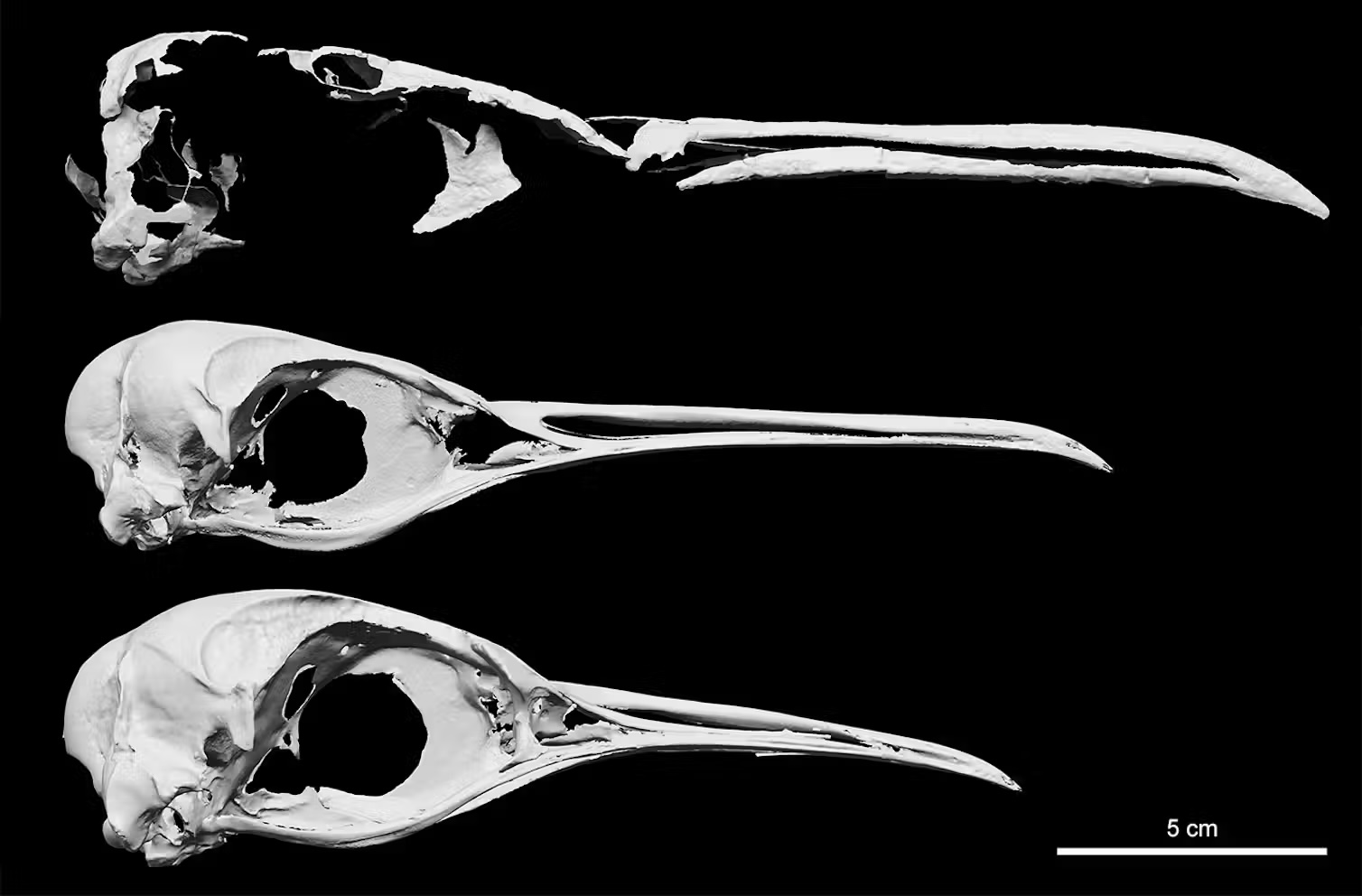

We know this because our new study explains the spectacular fossil skulls of great penguins found along the Taranaki coast.

You might like it

However, compared to the emperor penguins, the Taranaki’s great penguins were much stronger and had a longer beak. It probably looked like the penguin king (aptenodytes patagonicus), but only looked much larger.

At that time, the world was warmer than it is today. However, when the climate cooled, the penguin disappeared.

We argue that the cold was not responsible as New Zealand crested and small penguins survived the same change. The great penguins have moved south and today live in frozen waste in Antarctica. So what drove their ancients against extinction?

The sediments currently forming beachside cliffs in South Taranaki were deposited when they were above about 3°C global temperatures in the pre-industrial era. Fossils of this era have changed our understanding of how biodiversity responds to rising temperatures.

For example, the Aotearoa is home to boxfish and monk seals, both of which are today’s (sub)tropical species. In a strange contradiction, they coexisted with the great penguins in ancient New Zealand, which are now only seen in much colder climates.

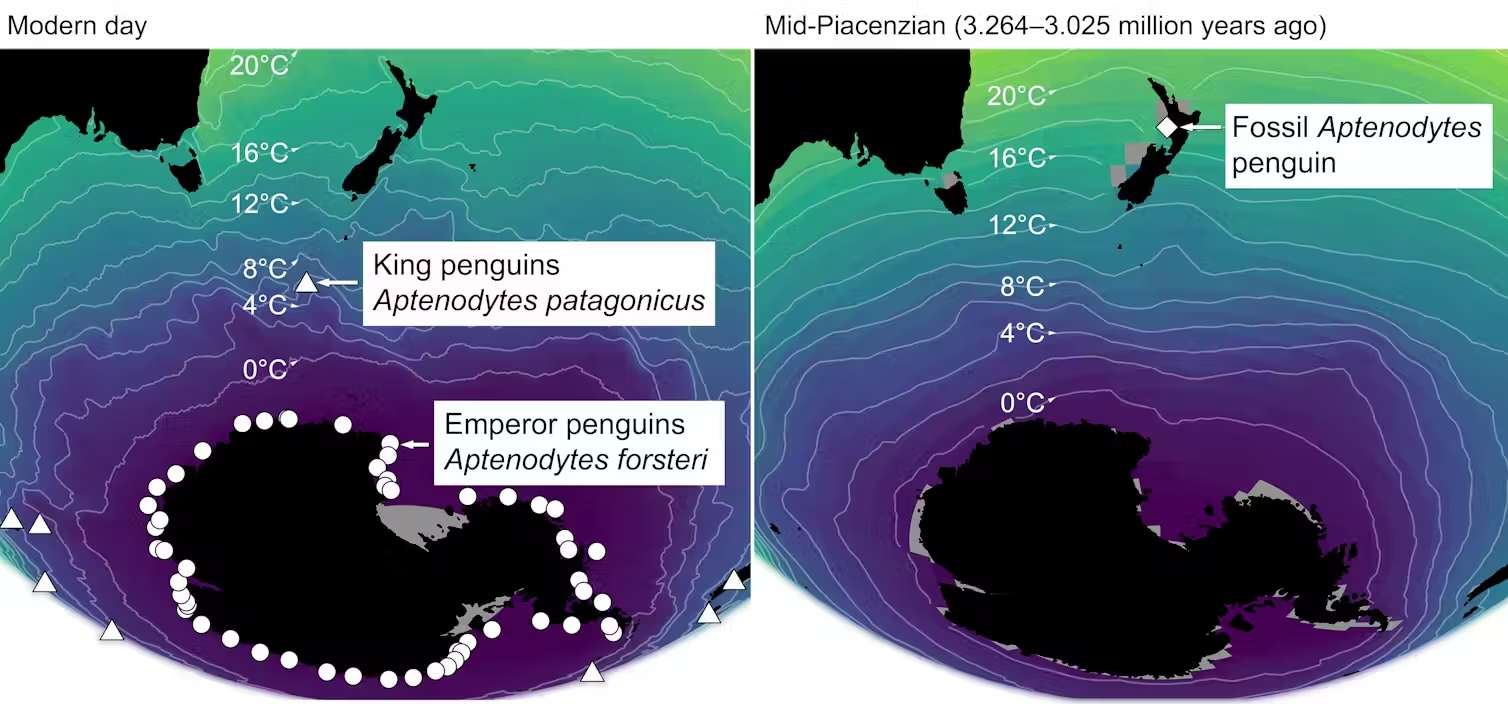

Today’s northernmost breeding colony of King Penguins is around 46.1° latitude on the sub-Antarctic Closet Island, where sea temperatures reach 3-10°C. From there, it only gets colder towards the higher latitudes where the emperor penguins live.

Three million years ago, the great penguins of Aotearoa had extended to 40.5°S, 40.5°S, where Southern Taranaki is located. They foraged in 20°C waters, much warmer than our relatives’ experience today.

You might like it

This refreshing presence ended with Pleistocene ice, about 2.58 million years ago. The temperature fluctuated and eventually ratcheted downwards, causing a shift in ice range and sea level back and forth. But why does this cooling eradicate the giant penguins that are thriving today in the polar regions from New Zealand?

Giant Aerial Predator

Fossil evidence of the giant penguins of Aotearoa is limited, and the exact reason for their ending mise remains unknown. Yet their pure presence suggests that sea surface temperatures are less constrained than previously thought. There must be another mechanism at work.

Until about 500 years ago, Aotearoa was a hunting ground for the giant hearst eagle and the giant Forbes Harrier. These were large birds of prey. They included big birds like MOA in their diet. Their ancestors have arrived from Australia within the last 3 million years.

Based on what we saw with the great penguins we live in, the Taranaki Great Penguins almost certainly formed large exposed colonies along the coast. These could have been easy targets for giant eagles and hunting from the air.

In contrast, the small penguins still seen in today’s Aotearoa have more inexplicable breeding behaviors. They tend to nest in dens, natural gaps, dense vegetation and cross the beach at night.

However, predation on the land is just one hypothesis that it helps explain why these penguins have been extinct in the region and yet others survived. Other possibilities include changes in the marine environment.

We know that a decline in food availability can be devastating for penguins, but it’s hard to see why this picks out great penguins.

Importantly, our research provides new insights into the resistance of great penguin habitats. Today, both kings and emperor penguins can withstand temperatures up to 20°C more than what they normally forage.

Three million years ago, their relatives experienced such warmth. It is important to remember that as the world continues to warm, the geographical range of species can change as circumstances change.

The marine ecosystem of Aotearoa has moved into habitable zones of many new species, making the final warm period more important than ever.

We would like to thank Dan Ksepka of the Blues Museum, the Blues Museum, for discovering the fossils, and Dan Ksepka, co-author of the study, Nagati Ruanui and ngāruahine, for supporting the collection and research of the fossils from Rohe.

This edited article will be republished from the conversation under a Creative Commons license. Please read the original article.

Source link