As humans evolved, our heads became larger and walking upright narrowed our birth canals. This means that in most cases you will need to help with everything from emotional support to intervention and medical assistance for life-threatening conditions such as high blood pressure, uterine rupture, and postpartum hemorrhage. Although depictions of pregnancy and birth rates predate written records, little is known about how pregnancy and birth were viewed and treated.

In this excerpt from “Born: A History of Childbirth” (Pegasus Books, 2025), author and historian Lucy Inglis reveals ancient Egyptian records that show how women’s doctors dealt with “womb” issues, how men responded to periods, and how the first known pregnancy test actually worked.

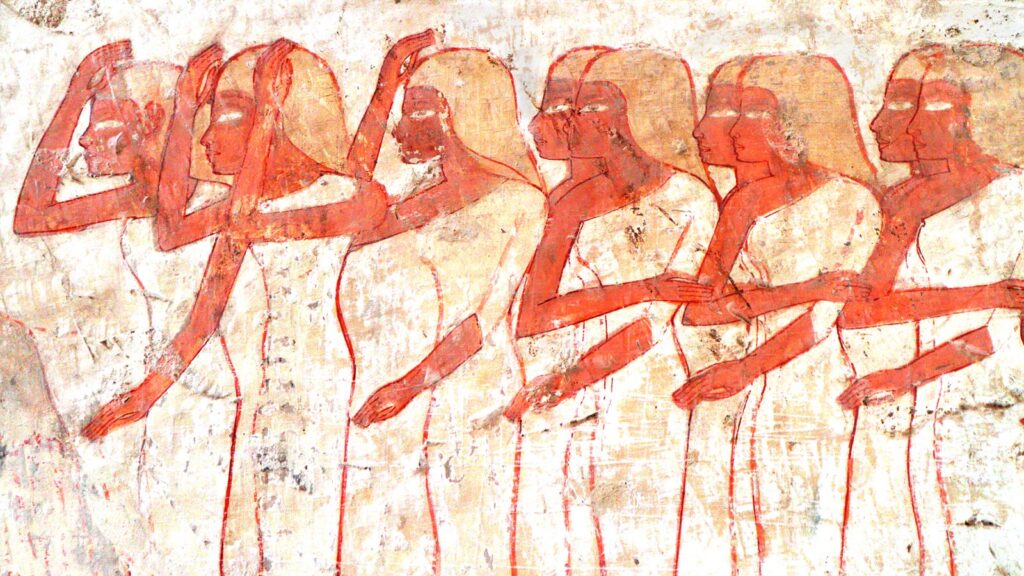

There is one female physician who lived during the construction of the great pyramids around 2500 BC. Her name and occupation are because her name and occupation were recorded on the door of the tomb of the son of Peseshet: Saqqara, the overseer of female doctors.

you may like

Women like Peschetto were respected professionals, not local wise women. Her son Akhetotep was a royal official, so his mother was firmly embedded in the class of literary elite. But at the door of the tomb, there remain as many questions as there are answers.

Who was the female doctor she supervised? Who and what did they deal with? The “professional” middle-class peseshts and tattooed priests also left the world’s first specific gynecological text, the “Kahun Gynecological Papyrus,” dating from 1825 BC. It contains 34 paragraphs of advice that most doctors today do not recommend following, diagnosing almost all women’s complaints as “uterine” complaints.

Examination of a woman with what sounds like a migraine, “on top of the pain in the neck, the eyes hurt until they hurt,” leads to the conclusion that she must have “uterine discharge in her eyes.” This is treated by “fu-steaming her with incense and fresh oil, fumigating her womb, and tempting her eyes with goose-leg fat. You must feed her the liver of fresh ass.”

Seducing her uterus didn’t help, but perhaps the liver at least provided some welcome nourishment.

Only one trial, which sounds like prolapse, correctly points to true involvement of the uterus itself. Which part of the body is not identified, although it is treated with the anointing of oil. Papyrus also recommends placing a clove of garlic in the vagina before bedtime. If your breath smells like garlic the next morning, things are going well for your pregnancy. If not, it’s sick.

However, Papyrus is also notable for the first use of the term “wandering womb”. This is a term that haunts women in various guises for another two thousand years. Deir El-Medina’s workers’ perfect record-keeping also includes an interesting entry for absence, known as HSMN, meaning menstruation.

A set of tablets written during the reign of Ramses II covers 280 days during which 10 prominent workers took “sick days” for the HSMN. This is something of a puzzle because men don’t menstruate. However, this meaning is made clear by the fuller entry of scribe Qenhikhopshef on the 23rd day. He was away because his wife was “having her period.” That winter, Neferhotep, the foreman of the works, also took his daughter’s period off.

you may like

Historians of the past century have concluded that this must mean that the Egyptians considered the menstruating body to be “unclean,” but this is just speculation. There is an ancient Nubian custom still seen in modern-day Ethiopia and Sudan, warning that menstruating or pregnant women should not enter cemeteries. Probably not a dirty woman, but a worker.

Rather than fear that the husbands of menstruating women might bring pollution to the sacred valley of the kings, male workers might have asserted their right not to “take home their work.” Doing so may have brought death into their homes when the women in the family were vulnerable.

The elites of any society leave behind for us monuments, art, literature, the purpose of which is to portray their patrons as somewhat superhuman, but the poor rarely leave any trace of their existence at all. Only relatively recently have their lives begun to be recorded for statistical purposes. It’s no surprise, then, that it is from the written records of the ancient Egyptian middle class that we learned about the first known pregnancy test, written around 1350 BC in a medical text known as the Berlin Papyrus.

It says: “Barley [and] Wheat, let’s add water to the woman [them] Every day her urine has a date [and] Sand, in two bags. in their case [both] Growing up, she endures. If the barley grows, it means a male child. If the wheat grows, it means a female child. If both of them don’t grow, she can’t stand it at all. ”

Amazingly, this theory was tested in 1963 and was found to be accurate in 70% of cases, although no success in gender determination was recorded. The test has since been repeated at various intervals through 2018, correctly identifying 70-85% of pregnant participants.

Excerpt from Birth: A History of Childbirth by Lucy Inglis. Published by Pegasus Books on October 7, 2025.

Source link