Quantum computing has long promised to revolutionize technology, but key obstacles have prevented it from reaching its full potential. That is, qubits, the basic units of quantum information, quickly lose data.

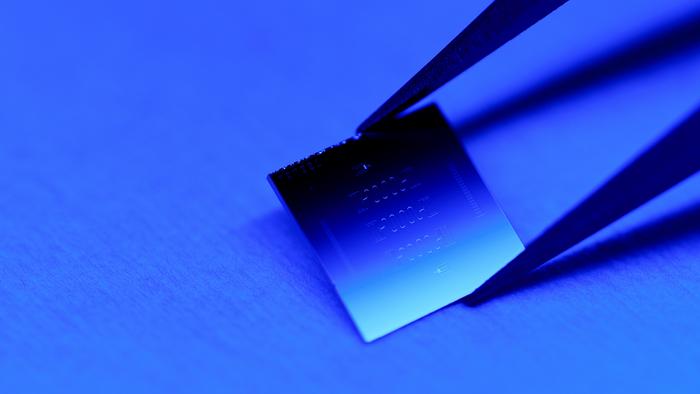

Now, engineers at Princeton University have built a quantum chip with qubits that last three times longer than any previous laboratory record.

This breakthrough dramatically improves the stability of quantum processors and brings practical large-scale quantum computing one step closer to reality.

The challenge of building a practical quantum computer

Quantum computers are expected to be able to solve problems that are currently impossible with conventional computers.

However, this technology is still in its infancy. One major limitation is the short lifetime of qubits. In current systems, qubits often lose coherence (essentially stored information) before completing any meaningful computation.

Extending the coherence time of qubits is important for performing complex operations, reducing errors, and scaling up quantum processors.

Princeton University’s latest results represent the most significant improvement in qubit lifetimes in more than a decade, raising hopes for more reliable and scalable quantum machines.

record quantum chip

A team at Princeton University reported that qubits maintain coherence for more than 1 millisecond. This is three times longer than previous laboratory records and nearly 15 times longer than the standard for commercial processors.

To demonstrate that potential, engineers built a fully functional quantum chip incorporating a new qubit and demonstrated that it can handle real-world operations, clearing a key hurdle for industrial-scale quantum computing.

The new qubit design is compatible with existing architectures used by leading technology companies.

Experts suggest that integrating Princeton’s qubits into processors like Google’s Willow could dramatically improve performance and make calculations 1,000 times more reliable.

As more qubits are added, the benefits grow exponentially, highlighting the long-term potential of this design.

Tantalum benefits

The Princeton team employed a two-pronged materials strategy to extend the lifetime of their qubits.

First, they used tantalum, a metal that is extremely robust and not prone to energy-trapping surface defects. These defects are common in metals such as aluminum and are a major source of qubit errors.

By minimizing them, tantalum allows qubits to store energy more efficiently, significantly extending coherence time.

The second key innovation was the replacement of standard sapphire substrates with high-purity silicon, the backbone of modern computing. The uniformity and availability of silicon makes it ideal for scaling quantum chips to industrial levels.

Growing tantalum directly on silicon required overcoming technical challenges related to its unique material properties, but the team was successful, unlocking unprecedented qubit performance.

Major advances in transmon qubit technology

The qubit design is built on the transmon architecture, a superconducting circuit widely used by companies such as Google and IBM.

Although transmon qubits operate at temperatures close to absolute zero and are relatively immune to external interference, improving coherence time has historically proven difficult.

By combining tantalum and silicon, the Princeton team achieved the largest single improvement in transmon performance in more than a decade.

This approach not only extends the lifetime of qubits, but also prepares the design of larger, industrial-scale quantum chips.

The resulting enhancements could scale exponentially, and a hypothetical 1,000-qubit processor using Princeton’s design could run roughly a billion times more efficiently than current systems.

The future impact of quantum computing

This breakthrough represents more than just a laboratory record. Princeton’s quantum chips address two key challenges in quantum computing: error correction and scalability by increasing the durability of individual qubits.

Longer qubit lifetimes reduce computational errors, making it possible to assemble larger qubit arrays without exponentially compounding mistakes.

Additionally, the use of silicon as the substrate will lead to industrial adoption of this technology. Silicon’s wide availability and compatibility with conventional electronics manufacturing could help bridge the gap between laboratory prototypes and commercially viable quantum systems.

These advances could finally bring quantum computers closer to solving real-world problems that remain beyond the reach of classical machines, from cryptography and drug discovery to complex simulations in physics and finance.

Princeton’s quantum chip demonstrates that hardware breakthroughs can directly translate into practical computing power, bringing the field one step closer to functional large-scale quantum computing.

Source link