Time crystals could help create quantum computing data storage that lasts minutes, new research shows. This significantly improves the millisecond duration of existing quantum data storage.

In the new study, scientists conducted experiments on how time crystals interact with mechanical waves. Although time crystals are widely considered to be extremely fragile, researchers have shown that they can be coupled to mechanical surface waves without destroying the time crystal.

“This is the most interesting part for me,” study co-author Jere Mäkinen, an Academy Research Fellow at Aalto University in Finland, told Live Science. “It means we can couple time crystals to other systems in important ways and take advantage of the inherent robustness of time crystals.”

you may like

The researchers described their findings in a study published October 16 in the journal Nature Communications.

Making waves in time crystal research

While traditional crystal structures have atoms or molecules arranged regularly in space, time crystals return to a specific state after a certain period of time. This is different from, for example, the oscillating frequency of a pendulum, which only reflects the frequency of the downward oscillating force, since gravity competes with the change in direction of the tension force. In the case of time crystals, they actually require an initial prompt to start working, but the periodicity is acquired spontaneously without driving anything at that frequency.

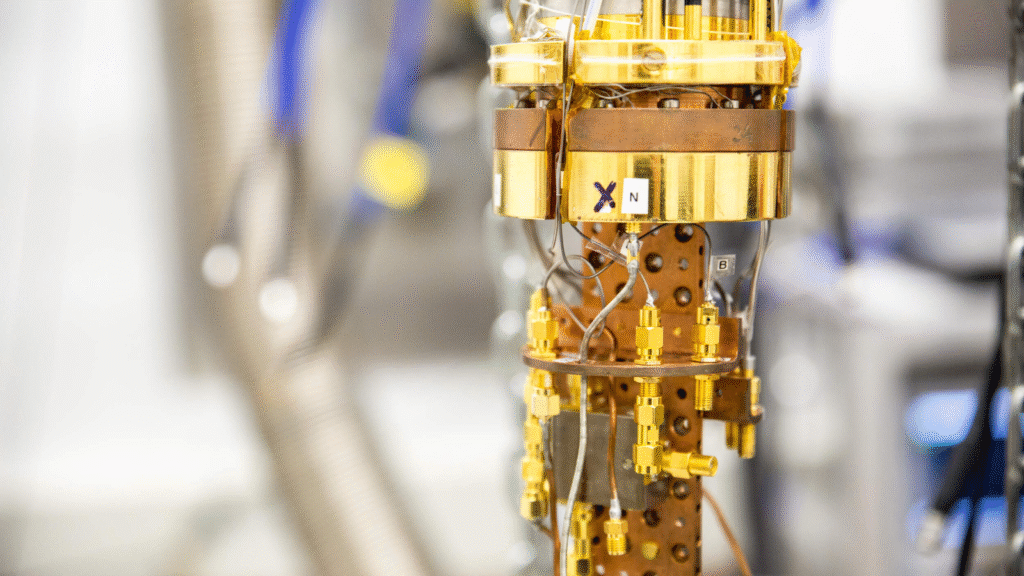

Since it was first proposed in 2012, various settings have been reported to act as time crystals. Mäkinen and his collaborators are based on quasiparticles called magnons, which are collective waves in the value of a quantum property known as spin. They created magnons in “superfluid helium-3,” or helium in which the nucleus has only two protons and one neutron, and the rotation of the particles in the nucleus does not cancel out.

They cool the helium-3 to extremely low temperatures, where atomic mechanics weakly but effectively attract each other to reorganize it into quasiparticles known as Cooper pairs. As Cooper pairs, these quasiparticles limit the available quantum states to only one, thus eliminating fluid viscosity.

We find that sloshing superfluid helium-3 back and forth with mechanical surface waves has an interesting effect: the surface influence on the spin and orbital angular momentum of Cooper pairs. These effects are properties used to characterize superfluids. To visualize this, consider the effect of a wall on the possible trajectory of a ball spinning at the end of a string. In free space, the ball’s trajectory can take any direction in three dimensions, but when it approaches a wall, some of these trajectories become impossible.

Mäkinen and his collaborators realized that this affects the period of the magnon time crystal. Their experiments show that time crystals can withstand interactions of up to several minutes. This suggests that data from a quantum computer could be coupled and stored in a time crystal through similar interactions.

In quantum computers, each qubit can superpose two binary states at once, which is the basis for theoretically higher processing power. Therefore, the memory of a quantum computer must store data that preserves the infinite quality of this qubit state.

you may like

Today’s quantum computer memory technologies commonly use spin orientation to store data, but these spin states are easily disrupted by environmental disturbances such as thermal noise. These disturbances induce the data into one of the possible states, and the quantum nature of the stored data is lost. Therefore, spin quantum memory lasts only a few milliseconds.

In contrast, the magnons created by Mäkinen and his collaborators persisted for several minutes even in the presence of mechanical surface wave disturbances. Surface waves leave traces in the magnon time crystal frequency and can therefore be used to “write” quantum data to be stored. Longer quantum memories enable more complex tasks because more quantum processing operations can be implemented on the data before it degrades.

Textbook analogy

After examining the experimental data, the team also found some similarities with optomechanics, where optical and mechanical resonators interact. An example is the barely perceptible impact of a photon hitting a mirror attached to a spring. In this case, as photons bounce off the mirror, the spring gains or loses energy.

Comparing time crystals and optomechanics reveals theories from the established field of optomechanics that can be applied to time crystals affected by mechanical waves, potentially giving us a head start in understanding these interactions.

“Optomechanics is a very common topic in many fields of physics, so it can be used in a wide variety of systems,” Mäkinen said.

Nikolai Zherdev, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Southampton who also researches time crystals and optomechanics but was not involved in the study, called the work “interesting” and told Live Science via email that it “opens up directions for research in the physics of nonequilibrium systems with potential implications for advances in quantum sensing and quantum control.”

Mäkinen said he is keen to explore different types of setups that mechanically couple to time crystals, such as nanofabricated electromechanical resonators, which have much lower masses than superfluid surface waves. “The obvious idea is to actually go towards the quantum limit and see how far we can push it,” he said.

Source link