Eruptions of some mid-ocean volcanoes may be echoes of the breakup of supercontinents that lasted tens of millions of years after the Earth’s surface was rearranged, a new study suggests.

A new study suggests that long after the continents broke apart, mantle instability caused by the breakup continues to erode the bases of the continents, stripping away their crust and supplying oceanic volcanoes with abnormal magma.

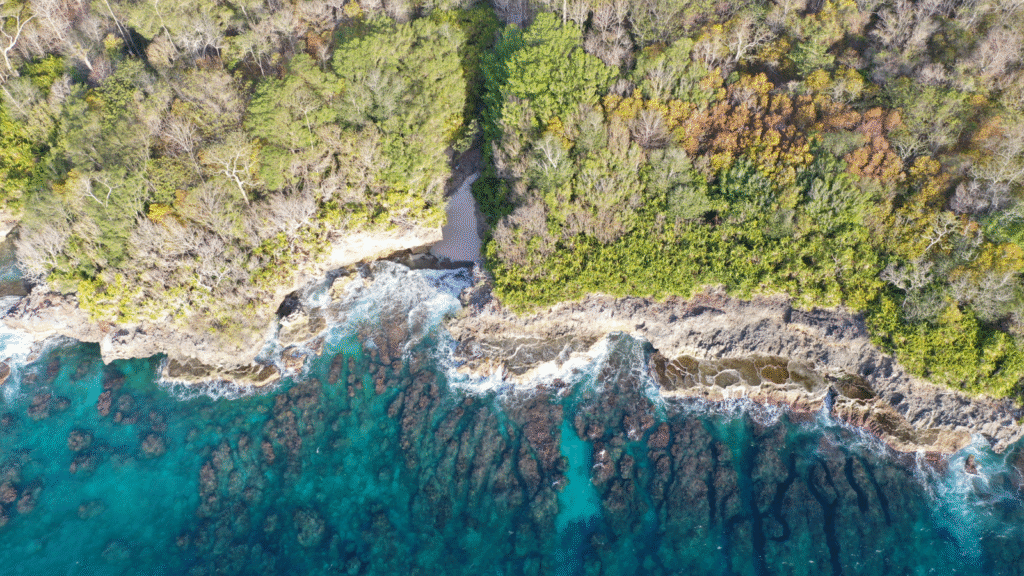

This phenomenon could explain why these volcanoes exist and form oceanic outposts like the Christmas Island Seamount, a mountain range in the Indian Ocean. One of them, Christmas Island, juts out into the sea. This is a nature reserve famous for its lush rainforest and the annual migration of millions of crabs (Gecarcoidea natalis) that cover the island with their red shells.

you may like

Thomas Garnon, professor of geology at the University of Southampton in the UK and lead author of the new study, said in a statement that the discovery represents a “completely new mechanism” for shaping the composition of the mantle.

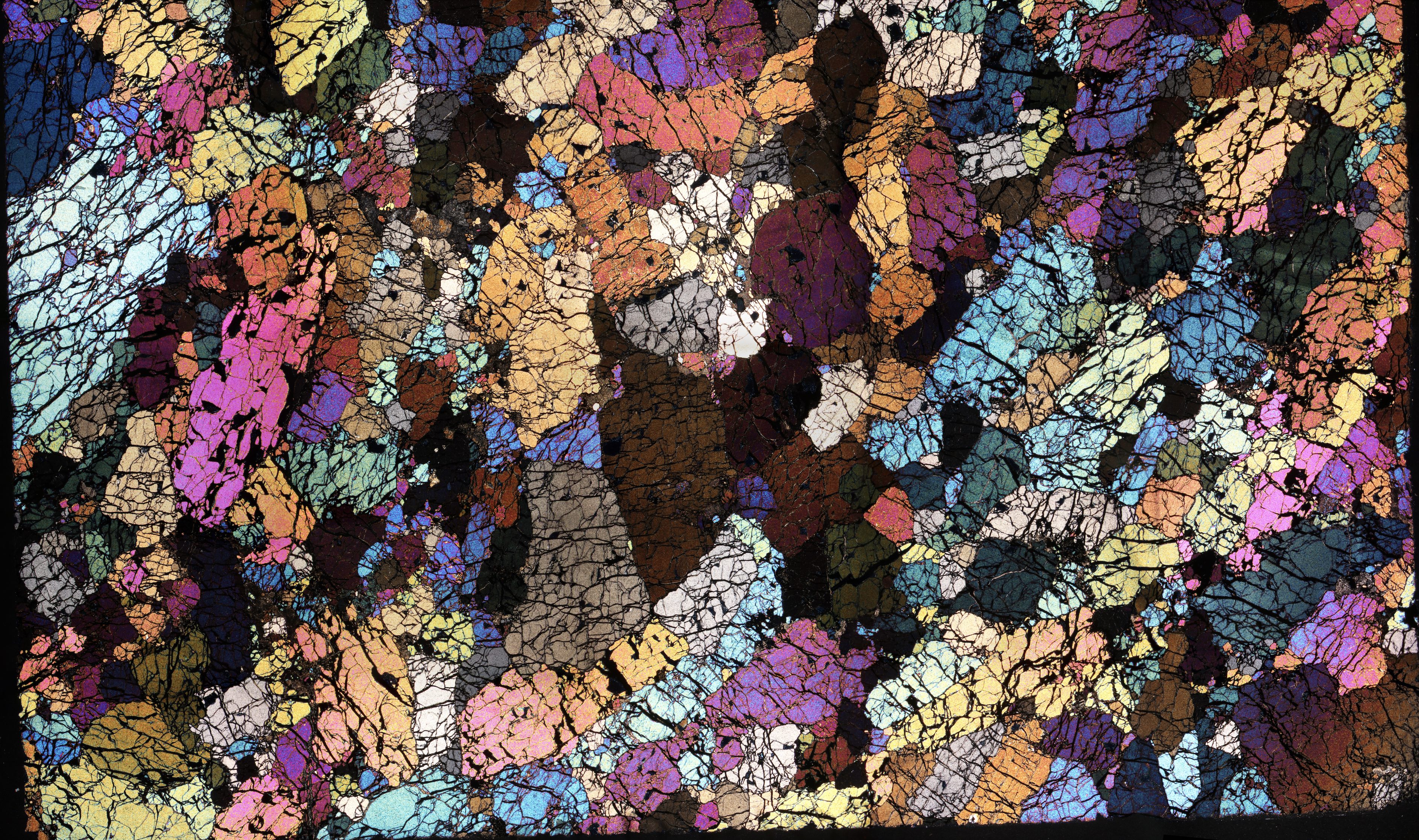

Christmas Island seamounts and similar underwater volcanoes have magma with strange compositions. It contains minerals more similar to continental crust than oceanic crust. Researchers hypothesize that these volcanoes are probably dredging up remnants of oceanic crust that sunk into the mantle long ago, transporting coastal sediments from the continents.

Another idea is that mantle plumes (upwelling of rocks from deep within the mantle) are bringing ancient continental material back to the surface. But anomalous magmas are so different that there may not be a single source that explains them all, Gernon and his colleagues said in a new paper published Nov. 11 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Rather, Gernon and colleagues suggest that these volcanoes may be fed with continental rocks of varying ages and compositions that were shed into the mantle after the continents catastrophically broke apart. They examined the volcanic rocks of Walvis Ridge, an oceanic ridge that begins near northern Namibia and extends far from Africa. These rocks showed a pattern in which older eruptions contained continental-like magmas that gradually transitioned to compositions more similar to oceanic rocks.

Using computer models, researchers found that after a continent breaks apart, a series of rolling waves in the mantle can advance toward the interior of the moving continent, scraping away the underlying continental crust like a potato peeler would peel a potato. Simulations show that this mineral-rich material enters the mantle within a few million years of continental breakup and does not return to the surface for about 5 million to 15 million years. This process supplies tens of millions of years’ worth of continental rock to the mantle, reaching a peak about 50 million years after the continents crack.

To test these ideas in the real world, the researchers next turned to the Christmas Island seamount and again studied the age and composition of the volcanic rocks there. They found a pattern consistent with their simulations. About 116 million years ago, 10 million years after India separated from what would become Antarctica and Australia, the first seamount volcanoes began erupting. The magma was rich in continent-like minerals, a pattern that peaked within 40 to 60 million years of breakup. This enrichment gradually decreased over time, and the magma began to look more like typical oceanic rocks.

The findings show that continental breakup is having long-term effects, the study authors said.

“We show that the mantle is still feeling the effects of continental breakup long after the continents themselves have separated,” study co-author Sacha Brune, a geodynamicist at Germany’s GFZ Potsdam, said in a statement. “As new ocean basins form, this system does not turn off. The mantle continues to move, reorganize, and transport concentrated material far from its place of origin.”

What’s Inside the Earth Quiz: Test your knowledge about Earth’s hidden layers

Source link