The X-Food Research Laboratory uses co-culture fermentation as a platform to develop environmentally friendly packaging materials.

When crustaceans such as lobsters, shrimp, and crabs are processed for human consumption, approximately 45-60% of their total mass becomes waste. Furthermore, only a portion of this waste is used as animal feed or fertilizer, and the rest is often dumped in landfills or oceans, which can be a potential source of pollution. Therefore, shellfish waste management is a critical issue. The inedible exoskeletons of crustaceans such as lobsters and shrimp are rich sources of calcium, protein, and chitin.

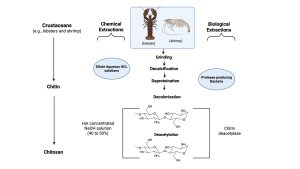

Chitin is a natural polysaccharide that serves as the structural backbone of the exoskeleton of crustaceans. Chitin and its derivative chitosan have exceptional film-forming, antibacterial, and biodegradable properties, making them strong candidates for sustainable packaging materials. Traditional chitin extraction methods involve chemical processes that produce corrosive chemical waste, which poses disposal issues and can cause environmental pollution.

Disadvantages of chemical chitin extraction

Chemical extraction methods include grinding the shells and exposing them to concentrated acids (hydrochloric acid) and alkalis (sodium hydroxide) for demineralization, deproteinization, depigmentation (using acetone or ethanol), deacetylation to form chitosan and depolymerization to form chitosan oligomers. Traditional chemical extraction methods rely on concentrated acids and alkalis, which generate large amounts of hazardous wastewater and reduce the quality of recovered biopolymers. To address these issues, the X-Food Research lab uses microbial fermentation as a more sustainable route to recover chitin with minimal environmental impact.

X food method

X-Food Research Laboratory’s two-step fermentation process mimics natural biodegradation under controlled conditions. In the first step, lactic acid bacteria are introduced into a slurry of finely ground lobster shells, mixed with a carbohydrate substrate and fermented for several hours. During fermentation, these microorganisms produce organic acids, primarily lactic acid, which gradually dissolve the calcium carbonate minerals embedded in the shell. This mild acidification step, known as biological demineralization, effectively softens the shell matrix without the need for harsh chemical reagents.

Once demineralization is complete, the material undergoes the second step of the process, biological deproteinization. In this step, protease-producing bacteria secrete enzymes that degrade protein components that are tightly bound to chitin fibers. This step releases the chitin polymer while allowing the recovery of protein that can be reused for other uses such as animal feed or fertilizer.

The process is streamlined using an approach known as co-culture fermentation, where multiple types of lactic acid bacteria are introduced into the mixture and the microbial species act synergistically during fermentation. Co-fermentation not only reduces processing time but also has the potential to reduce operational costs and simplify downstream purification. At the end of fermentation, the extracted chitin is carefully washed, dried, purified, and its properties evaluated. These analyzes are necessary to better define the critical parameters that influence the functionality of packaging material applications. Purified chitin biopolymers are blended with protein-rich ingredients from other food manufacturing processes, such as soy protein and other plant sources, to develop composite materials suitable for packaging. These blends are cast into thin films and evaluated for tensile strength, flexibility, water vapor permeability, and biodegradability.

Although our preliminary results show that fermentation-derived chitin and chitosan films are promising and that in some respects the films have properties comparable to traditional packaging materials, more work needs to be done to improve the strength and flexibility of the films. The combination of lobster shell waste and protein byproducts provides an example of a circular system, with the potential to convert waste streams into high-value, sustainable materials.

Environmental benefits of microbial processes

Currently, microbial processes require longer processing times than chemical methods, but offer significant environmental benefits, including reduced energy input and chemical waste. Therefore, research beyond the laboratory should focus on exploring the scalability and economic feasibility of fermentation-based chitin extraction. These processes must integrate chitin extraction with protein, pigment, and mineral recovery to maximize the overall resource efficiency of seafood processing. With increasing demand for eco-friendly packaging and increasing regulatory pressure to reduce single-use plastics, microbial co-culture fermentation of shell waste could play a central role in advancing innovation in the sustainable materials sector.

This article will also be published in the quarterly magazine issue 24.

Source link