A research team at Graz University of Technology has developed a new way to improve the efficiency of aircraft engines using an in-house AI-supported model.

With its Flightpath 2050 strategy, the European Commission has outlined a framework for the aviation industry to reduce emissions and fuel and energy consumption, requiring more efficient aircraft engines.

The ARIADNE project has created the basis for achieving the desired efficiency gains more quickly. Researchers combined years of flow data on intermediate turbine ducts with AI and machine learning.

This led to the development of a model that more quickly and efficiently tests the effect of changes to a wide range of geometric parameters on efficiency.

Intermediate turbine ducts offer optimization possibilities

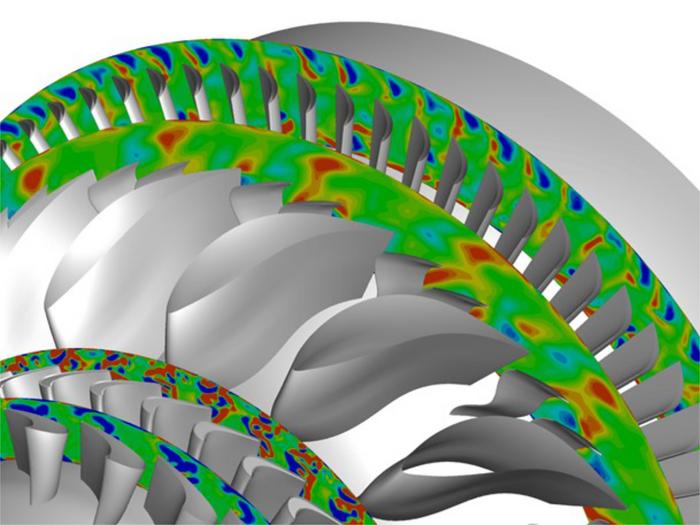

“Intermediate turbine ducts are important components of aircraft engines,” explains Wolfgang Sanz, project manager at the Institute of Thermal Turbomachinery and Mechanical Dynamics at Graz University of Technology.

“They guide the flow between high-pressure and low-pressure turbines operating at different speeds. However, these intermediate ducts are very heavy, so they need to be as short, small and light as possible while achieving high efficiency. There is still a lot of optimization potential here.”

The institute has built an extensive database of measurement data and flow simulations based on original research in collaboration with prominent aircraft engine manufacturers.

To harness this treasure trove of information to optimize components and the engine as a whole, the team, in collaboration with Franz Wotawa’s research group at the Institute of Software Engineering and Artificial Intelligence at the Graz University of Technology, and two corporate partners, pursued three different AI-powered approaches.

Reduced order models are most likely to produce efficient aircraft engines.

Reduced-order models have proven to be the most successful because they search for similarities in the data and use only the most important common features for simulation.

This significantly speeds up the computation, performing several orders of magnitude faster than a full flow simulation. Although these models may come with some loss in accuracy, they can be linked to simulations to predict trends and identify potential optimizations.

Another advantage of the independently developed model is the ability to quickly recognize changes in the performance of an efficient aircraft engine when parameters such as the length of the transition duct change.

In contrast, surrogate models primarily rely on interpolation of existing data and therefore have certain limitations. Outside of the validated flow data, the database was too small and the results were inaccurate.

The project also investigated PINNs (Physics-Informed Neural Networks), which aim to integrate physical differential equations into neural networks.

However, further development is required before it can be used in practice to test more efficient aircraft models.

Next steps: 3D simulation development

The research team is already planning next steps, as the reduced-order model has so far only modeled the intermediate turbine duct in two dimensions.

The extensive database of turbine ducts and low-order models developed in this project will be made available online to other research groups to work on three-dimensional simulation models of aircraft engines.

But for Sanz, leveraging machine learning is already opening up new approaches.

“The results of our machine learning approach allowed us to recognize dependencies and trends that we would never have considered otherwise,” he concluded.

Source link