More than 70 years ago, astronomers at California’s Palomar Observatory captured several star-like flashes that appeared and disappeared within an hour, a few years before the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, was launched into orbit.

A new peer-reviewed study revisiting these midcentury skyplates reports that these fleeting points of light, called transients, appeared on or near the days of Cold War-era nuclear weapons tests, coinciding with a historic spike in UFO reports. Are all of these related? Researchers are trying to find out.

Such flashes can be traced back to natural phenomena such as variable stars, meteors, or instrumental oddities, but some of the Palomar phenomena share unique features, including the shape of several sharp points that appear to be arranged in a straight line, which the authors of the new study say contradicts any known natural or instrumental causes.

you may like

“If before Sputnik it turned out that the transient was a reflective man-made object in orbit, who put it there and why are they interested in nuclear testing?” Brühl added.

However, not all researchers agree on this interpretation of the image. Some experts have noted that technical limitations at the time made this data very difficult to reliably interpret. Michael Garrett, director of the Jodrell Bank Center for Astrophysics at the University of Manchester, UK, who was not involved in the new study, praised Villarroel’s team for their creative use of archival data, but cautioned against taking these results too literally.

“My main concern is not the quality of the research team, but the quality of the data at their disposal,” he says. Villarroel’s team admits that pre-Sputnik data were poor, especially anecdotal reports of UFOs, or unidentified anomalous phenomena (UAPs), that they had not evaluated for plausibility.

light disappearing in the sky

Ephemeral objects are a recurring phenomenon in astronomy. Modern sky surveys such as California’s Zwicky Temporary Facility and Hawaii’s PanSTARRS have already detected thousands of these fleeting phenomena, and the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory is expected to identify millions of them each night over the next decade.

Many of these transients have been successfully linked to known astrophysical processes, such as sudden flares from comets and asteroids, the explosive death of stars, the variability of accreting black holes, and neutron star mergers that produce kilonova afterglows.

you may like

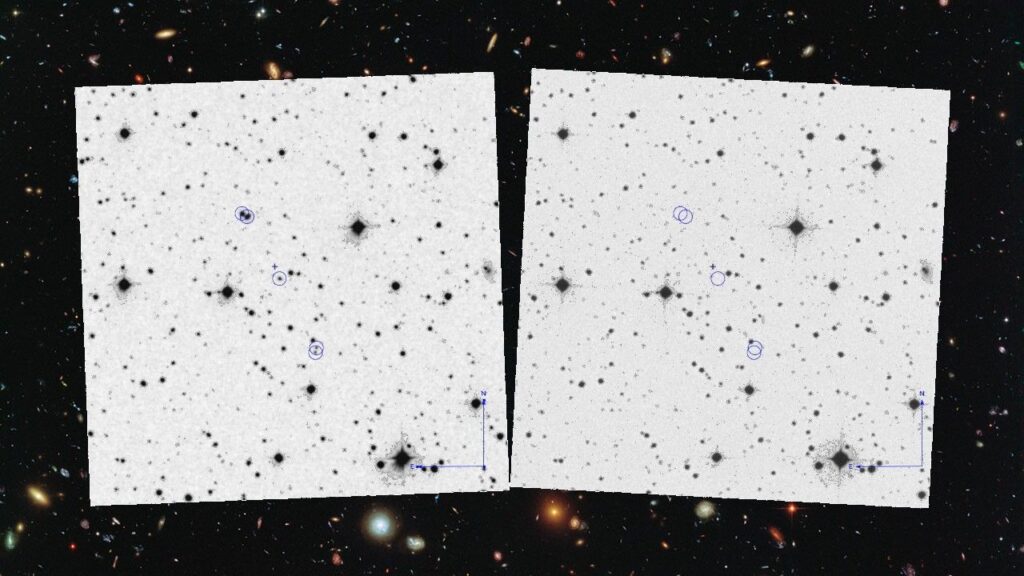

To look for such events in the pre-Space Age skies, the new study examined digitized images from the first Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS-I) conducted between 1949 and 1958. The survey relied on about 2,000 photographic glass plates, each coated with a light-sensitive emulsion that reacted to incoming light and preserved traces of stars, galaxies, and other celestial objects. These were manually loaded into the Samuel Ossin Schmidt telescope for a 50-minute exposure that captured a wide area of the northern sky, and then scanned and converted into a digital archive.

Villarroel’s team examined 2,718 days of survey data and found temporary sky phenomena on 310 nights. The phenomenon, which appeared as many as 4,528 flashes in multiple locations in one day, was absent from images taken immediately before or after the event, and from all subsequent sky surveys.

When compared to the UFOCAT database of historical UFO reports, the researchers found that transients were 45% more likely to occur within 24 hours of a ground-based nuclear test conducted by the United States, Soviet Union, and United Kingdom, and each additional UAP report on a given day corresponded to an 8.5% increase in transients.

The analysis, published Oct. 20 in the journal Scientific Reports, describes these as “more than coincidental connections” between the transients, nuclear tests, and UAP reports. The researchers say the discovery reflects long-standing speculation that extraterrestrial life is attracted to human nuclear activity, but the authors stress that the data does not prove causation.

But what if the opposite were true? A simpler explanation, some experts say, is that the flash, and perhaps some of the reported UFOs, were a byproduct of the nuclear explosion itself. Michael Wisher, a nuclear astrophysicist at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, told Scientific American that such an explosion could inject metal fragments and radioactive dust into the upper atmosphere, which could be seen as short bursts of light, similar to stars, when viewed through a telescope.

Villarroel and Brühl said they were considering that possibility, but countered that radiation glare and fallout contamination would result in diffuse smudges and streaks rather than the star-like dots seen on Palomar’s skyplate. And if the flashes were fragments of bomb casings thrown into orbit, the objects would have to reach about 22,000 miles (35,000 kilometers) above Earth, where modern geostationary satellites exist, to appear stationary in a 50-minute exposure.

Brühl told Live Science that such a scenario seems unlikely “unless a miracle happens.” “There is no simple explanation of what these transients are and why they appear in nuclear tests.”

incomplete past

Some other astronomers have suggested that the mystery probably lies not in the sky but in incomplete photographic plates and error-prone records from the time.

Robert Lupton, an astronomer at Princeton University who develops algorithms to extract meaning from optical data, who was not involved in the paper, said astronomy has a long history of misinterpreting apparent alignment. This includes the early debate over quasars, where astronomers once thought that the apparent pairs in the sky meant they were physically connected, but later discovered that they were just coincidental alignments.

“The hard part is knowing what the anomalies in the data actually are and how many other strange things we might have seen,” Lupton told Live Science. “I thought it would be wise but difficult to use pre-Sputnik data.”

The apparent alignment seen in the Palomar Observatory data could be due to imperfections in the photographic material itself, said Nigel Hanbury, a survey astronomer at the University of Edinburgh in the UK, who investigated the issue in a 2024 paper. False linear features can arise from everyday causes, he said. That is, they are diffraction spikes from bright stars that look like lines, dust, hair, or other debris stuck to an emulsion, mimicking aligned transients. In some cases, such artifacts can also be caused by scratches made during copying or digitization of old photographic plates, he said.

These problems are especially common when researchers work with copies rather than originals, as in Villarroel’s team, Hambly said, because flaws can remain even after generations of reproduction.

A turning point in UFO research?

Researchers interviewed for this article agreed that independent analysis is essential, and several suggested reexamining the same historical data and other archives of scanned plates from observatories active before 1957, ideally in the Northern Hemisphere, using a complete time series of images like those from Palomar Mountain. Hanbly added that reexamining the original Palomar plate itself and performing microscopic “forensic” testing could help determine whether the reported transients really appeared in the original or were introduced later.

Visually inspecting the plate can reveal the difference between genuine detection of emulsion and fake scratches “at a level of detail that is lost in digital scanning, even with very high-resolution imaging,” Hambly said.

Whether these mysterious flashes are evidence of unmanned aerial vehicles, secret military technology, or simply the product of past imaging, the ongoing debate highlights how science investigates the unknown and tests the unusual.

“Ultimately, I think the publication of these results will be looked back upon as a turning point in mainstream acceptance of UFOs as a legitimate research topic worthy of academic scientific investigation and intense media coverage,” David Wint, a research scientist at Columbia University who was not involved in these papers, told Live Science.

Source link