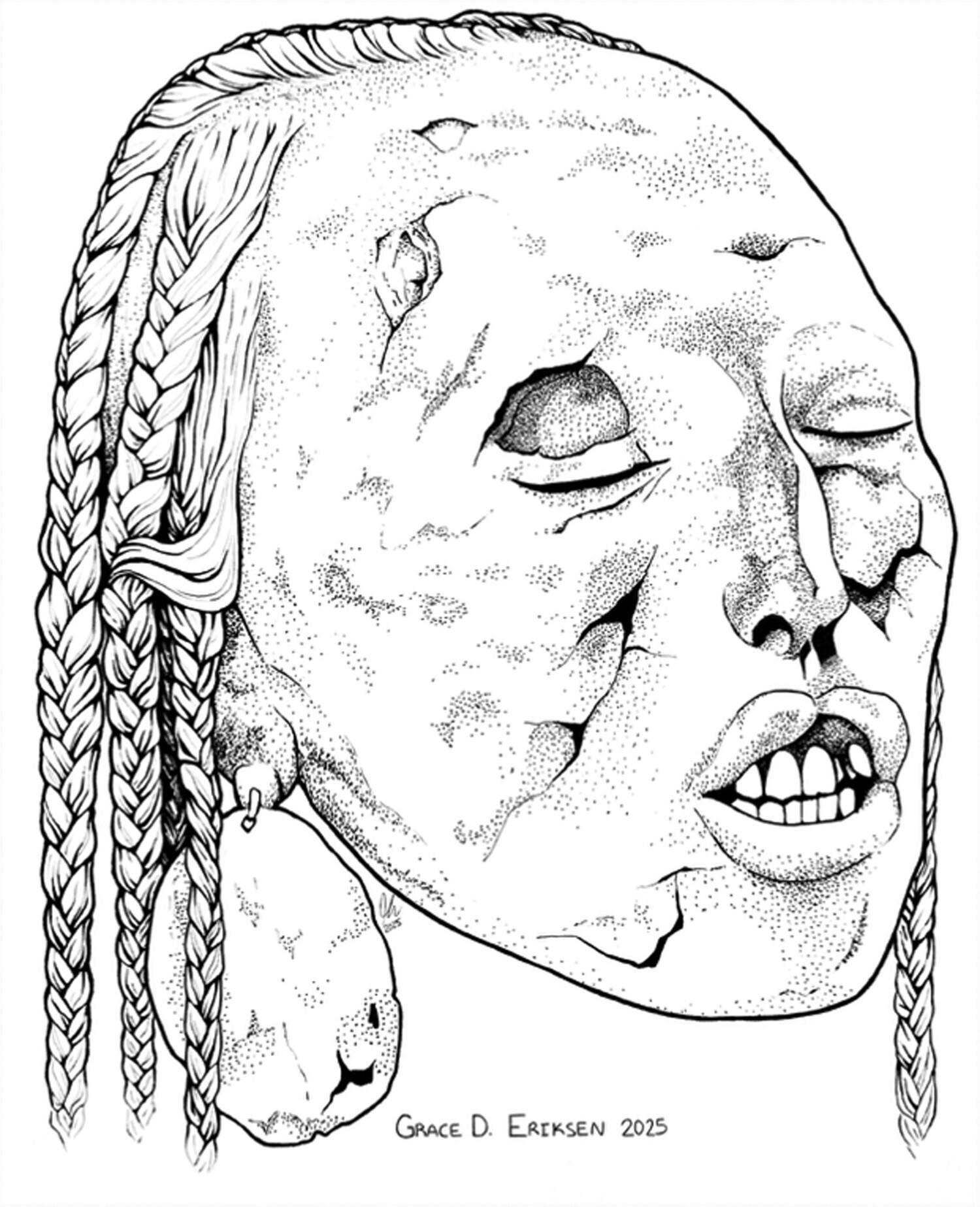

Centuries ago, the heads of decapitated people in Peru were turned into “trophies.” Now, a careful look at this trophy head reveals that it survived into early adulthood despite potentially problematic birth defects.

Beth Scafidi, assistant professor of anthropology and heritage studies at the University of California, Merced, writes in a new study that based on several photos of the head, researchers discovered that the person was born with a cleft lip.

you may like

The latest study, published Nov. 3 in the journal Nyaupa Pacha, is the first time that orofacial clefts have been documented on the heads of Andean trophies, and provides a “unique opportunity” to explore how ancient people in the region viewed such conditions, Scafidi said in the paper.

“This discovery is important because it shows that people survived and even thrived in these conditions in the ancient Andes,” Scafidi told LiveScience via email. “This helps show that what we define as a disability and how we respond to it is determined culturally, not biologically.”

trophy head

For thousands of years, ancient peoples living in and around parts of the Andes Mountains in South America have collected severed heads as trophies and processed them for preservation and display, Scafidi said. The best-known examples date from approximately 300 BC to 800 AD, and many originate near modern-day Nazca, in the Peruvian coastal department of Ica (Peru has 24 departments or regions). Scafidi said the trophy head was likely passed down from generation to generation as a family heirloom.

“Most trophies are naturally mummified in dry desert environments, often with hair and meat preserved,” Scafidi said. “While we still debate whether these heads are the lovingly collected remains of beloved ancestors or mementos of the violent conquest of an enemy, many also show violent wounds sustained before and after death.”

During a research project, Scafidi found an interesting example attributed to the squid department in the catalog of the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Saint-Étienne, France.

Scafidi examined photographs of the mummified head and determined that the person was likely male and a young adult at the time of death. Based on the visible facial structure, she diagnosed the person with cleft lip.

Perhaps the most serious complication of orofacial clefts is difficulty biting while breastfeeding, but these symptoms can also cause respiratory, hearing, and speech problems, she writes in the study. Today, these birth defects are usually treated surgically within the first few months of life, but in the ancient Andean world, they would have posed a significant challenge to mothers and caregivers during their babies’ infancy. For example, the individuals Scafidi studied likely required special care to obtain nutrition during infancy.

you may like

special status

But not only did these individuals survive into early adulthood, but their condition may even have given them special status, Scafidi said. Cultural reactions to orofacial clefts in ancient America ranged from shame to veneration. But especially given what is known about the worldview of ancient Andean people, Scafidi said, it’s likely that this figure was considered sacred and given a high-status role throughout his life and beyond.

In the absence of written or written sources, ancient ceramics from the region, particularly those made by the Moche culture of northern Peru (200-850 AD), provide clues to how congenital diseases were understood at the time.

In his research, Scafidi discovered 30 ceramic representations of orofacial clefts that had already been recorded in the Andean region, 20 of which were from the Moche region. Most of these examples depict men adorned with elite jewelry, head wraps, or performing shamanic or medical activities, suggesting that they were important figures. Other research has shown that birth defects were revered because the Moche believed facial markings protected against supernatural harm.

Previous research has shown that Andean trophy heads were often collected from individuals believed to have supernatural powers, and it was believed that those who obtained the heads could use those powers to benefit their communities.

Scafidi said the collection of this particular subject as a trophy head, even through potentially violent means, is consistent with the idea that orofacial clefts were celebrated by the laureate. Research shows that what is considered a disability today was probably considered a “blessing.”

Source link