Providing nerves with fresh mitochondria may help reduce chronic nerve pain, new research suggests.

The study, conducted in mouse cells, live mice, and human tissue, revealed a previously unknown role for mitochondria, the powerhouses of cells. This shows that supporting cells within the nervous system can transport mitochondria to nerves that respond to pressure, temperature, and pain. However, problems with that transport process can deplete nerve energy stores and cause dysfunction.

you may like

The new study, published in the journal Nature on Wednesday (January 7), points to a potential new way to prevent nerve cell destruction, and one strategy could involve transferring mitochondria directly into nerves.

Fresh mitochondria reduce pain

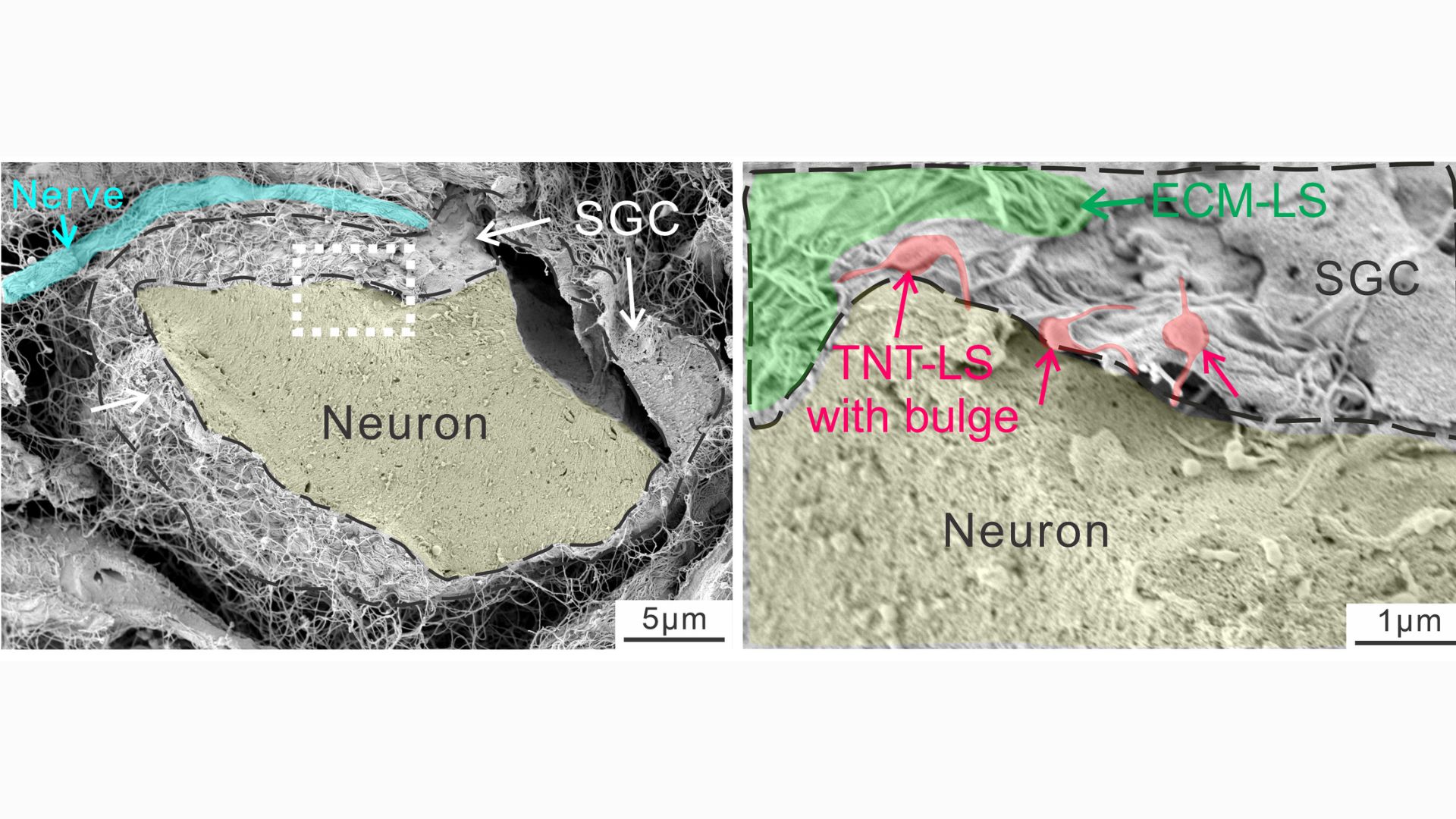

The study focused on satellite glial cells, unique cells that physically wrap around the “roots” of nerve cells located near the spinal cord. The body of these nerve cells is clustered near the spine, and from each cluster long bundles of fibers extend to different parts of the body from head to toe. The longest of these bundles belongs to the sciatic nerve and is just over 3 feet (1 meter) long.

Fiber length poses a “real challenge,” Ji said, because for nerves to function properly, the mitochondria produced in the nerve root must travel to the end of each fiber, which requires energy of its own. This raises the question of how nerves maintain this power-hungry supply chain.

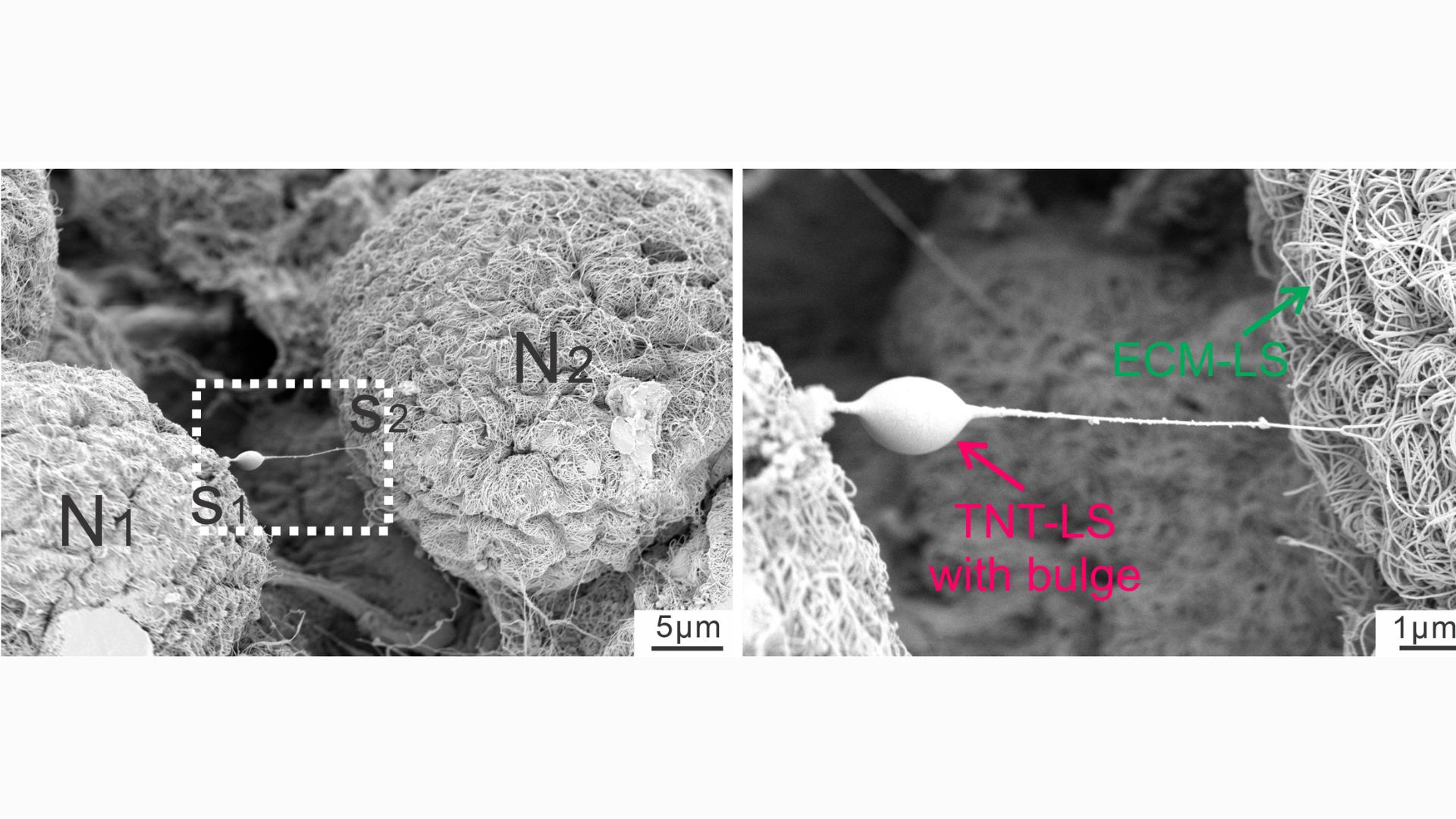

Scientists once thought that every cell had to make its own mitochondria, but in recent years they have discovered evidence that cells exchange mitochondria. This can occur between cells of the same type or between different types of cells, such as stem cells and immune cells. To facilitate this exchange, cells build small structures called tunnel nanotubes through which mitochondria pass. This looks like a saliva ball that slides from one end of the straw to the other.

Ji and his team wondered if satellite glial cells might be able to send mitochondria to the nerve cells they surround. And it turns out it can be done.

“We demonstrated that these cells actually extend the tunnel nanotubes and deliver them to the mitochondria. [finding] “This study is unique,” Ji said.

you may like

In a series of experiments using mouse cells and human tissue, the researchers took snapshots of the tiny tubes that form between glial cells and nerve cells, noting the distinct “bulges” that appear within the tubes as material passes through them. By attaching fluorescent tags to mitochondria, they were able to track cases in which powerful substances from glial cells invade nerves.

Nanotubes are temporary structures that break as soon as a given movement is completed. The experiments showed that a protein called MYO10 is important for tube construction and helps the tubes extend from the glia. But in addition, mitochondria can also be transported without tubes, either inside small bubbles released by glia or through special channels formed between the membranes of donor and recipient cells.

The researchers found that disrupting these different modes of mitochondrial transport in healthy laboratory mice made the mice more sensitive to pain. This is because it accelerated nerve damage and caused abnormal firing.

They also examined mice with different types of nerve damage, including from exposure to chemotherapy drugs and diabetes. These nerve-damaging conditions also disrupted mitochondrial exchange from glia to some extent, which contributed to neuralgia in laboratory mice. However, transplanting healthy glia into mice reduced pain by providing them with a fresh source of healthy mitochondria.

A new perspective on glia

In particular, nerve damage from diabetes or chemotherapy tends to hit the smallest nerve fibers hardest, whereas medium-sized and thick nerve fibers show more resilience. The researchers found that large nerve fibers seemed to receive more mitochondria from glia, while smaller nerve fibers received fewer. In other words, glia appear to “prioritize” lending mitochondria to larger fibers, the study authors wrote.

“It’s still a mystery. We don’t know why that happens,” Gee said. However, this may nevertheless begin to explain why small fibers become more susceptible to damage in these situations, causing symptoms such as numbness, tingling, and burning in the feet and hands.

Further research is needed to fully understand how mitochondria move from glia to neurons during health and disease. The research team believes this basic research could pave the way for future treatments for neuralgia. In theory, treatments could aim to increase the activity of satellite glial cells, allowing them to produce and transmit more mitochondria.

Alternatively, mitochondria could be harvested from cells grown in the lab, purified and injected directly into nerves as a treatment, he added.

Historically, glia were thought of only as the glue of the nervous system, providing structural support to neurons by connecting them together. But scientists have since discovered that glia are involved in processes previously thought to be handled only by neurons, such as memory. And new research suggests that glia may actually be physically connected to neural networks, Ji said.

“If we can transport mitochondria, which are such large organelles, in that tube, why not transport many other things?” he suggested. “This means that neurons and glial cells are much more closely connected than we realized.”

Source link