Scientists have created a new tool to observe plant respiration in real time. The new technology could help identify genetic traits that make crops more resilient to global climate change, the researchers said.

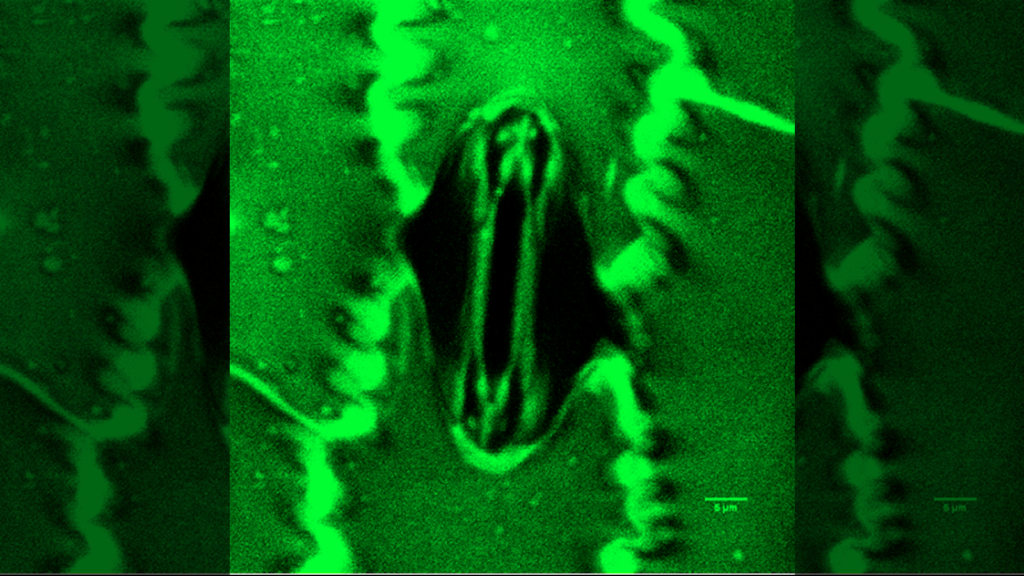

Human food systems rely on tiny holes in plant leaves. These microscopic pores, called stomata (Greek for mouth), control how much carbon dioxide a plant consumes and how much oxygen and water vapor it breathes.

you may like

Specialized cells surround the pore opening and expand and contract to open and close the pore. But scientists still don’t know exactly how individual stomata control what goes in and out of plants.

“Despite the fact that we’ve been studying stomata for a very long time and know a lot about stomata, we’re having a really hard time connecting our understanding of how much oxygen, water, and carbon enters and exits the stomata with the number of stomata, the size of the stomata, and how the stomata open,” Leakey said.

To better understand this process, researchers developed the Stomata In-Sight tool. The tool is described in a study published in the journal Plant Physiology on November 17, 2025. The Stomata In-Sight instrument combines a microscope, a system that measures pore gas flow, and image analysis with machine learning. “We measure the collective activity of thousands of stomata in terms of carbon dioxide and water fluxes,” Leakey said.

To use Stomata In-Sight, Leakey explained, a small piece of leaf is placed in a temperature-controlled chamber the size of a human palm that is connected to a gas exchange system. Researchers can change the conditions inside the chamber to see how the pores respond to changes in temperature, water availability, and other parameters. A microscope is placed outside the chamber, and while peering inside, machine learning analysis identifies pores from the microscope images, speeding up analysis.

It took the team several years to develop the new tool. The big problem is that small vibrations, such as from fans in gas exchange systems, can blur the image. “This actually took about five years and probably three failed prototypes before we arrived at the final solution,” Leakey said.

The research team has already used this system to observe the stomata of corn (Zea Mays) and other crops. They also used insights about stomata to process sorghum (Sorghum bicolor, a type of plant grown for grain) to use less water. They identified genes involved in the density of stomata in sorghum leaves and engineered plants with more widespread stomata.

The technology has been patented by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and although it is not commercially available, Leakey is hopeful that companies may be interested in manufacturing the device for other research groups.

you may like

But not all scientists are convinced. Alistair Hetherington, emeritus professor of botany at the University of Bristol, UK, doubts whether this new tool will revolutionize the study of stomata.

“We have been able to measure changes in stomatal opening using conventional microscopy for over 100 years, confocal microscopy for perhaps 25 years, and so-called gas exchange techniques for 50 years,” he told Live Science. Although the new study brings these techniques together, Hetherington added that researchers are likely to stick with “existing techniques that have proven efficacy.”

Nevertheless, Leakey is considering improving the tool to broaden its usefulness. The main challenge at the moment is that observing stomata “breathing” is very time consuming. “If you look through a microscope, you’ll see on average two to three stomata within a small leaf,” he explained. “But you actually have to measure 40 to 50 pores to account for variability.” This must be done manually.

Also, it may take several minutes for the stomata to respond to changes in conditions. This means scientists must wait until the stomata have finished opening and closing before taking another image.

“This is very labor intensive, but there is potential to use robotics and artificial intelligence to turn it into a production line process,” he said. “The scientific community is very excited about how biological research can be accelerated using these types of tools.”

Source link