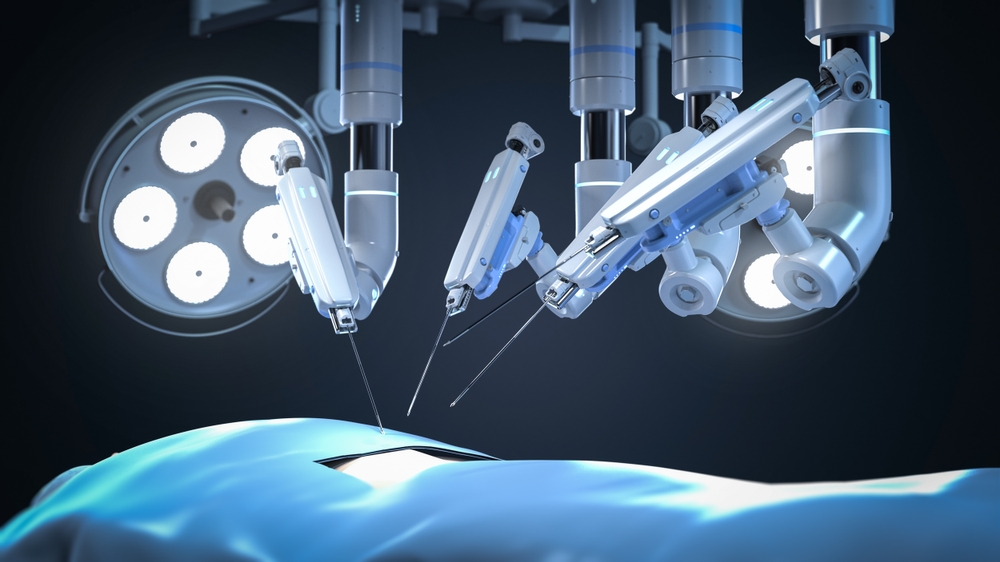

Researchers are developing a robotic “fingertip” that can restore a surgeon’s sense of touch during minimally invasive robotic surgery.

Modern surgery has moved from long incisions to smaller incisions guided by robots and AI. But in the process, surgeons lost something important: the opportunity to feel directly inside the body. Without palpation, it is difficult to detect tissue abnormalities during surgery.

A group of surgeons and technicians across Europe are currently working to restore this important aspect of surgery.

In an EU-funded research collaboration called PALPABLE, they are developing a soft robotic “fingertip” that can sense tissue hardness and softness during minimally invasive robotic surgery. The research will run until the end of 2026, and the first prototype is expected to be tested by surgeons around March 2026.

By combining optical sensing, soft robotics and AI, the team is designing a probe that mimics the way a fingertip presses and feels during surgery. It gently probes the organ and creates a visual map of tissue stiffness that is displayed on the screen to help guide the surgeon during surgery.

lose the surgeon’s touch

For many surgeons, the loss of direct contact has been one of the silent trade-offs of modern surgery.

“We started 30 years ago with open surgery and using fingers,” said Professor Alberto Arezzo of the University of Turin in Italy. He specializes in minimally invasive and robotic surgery, primarily treating colorectal cancer patients.

“Then we moved into the era of keyhole surgery. We started using longer instruments, which reduced tactile feedback,” he said.

Since the 1990s, keyhole surgery has become increasingly common, allowing surgeons to operate through small incisions with the help of cameras. Patients benefited from less trauma, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery.

But this came at the cost of physical contact. Tumors often feel different than healthy tissue, being harder, less flexible, and irregular, so experienced hands can detect important differences.

Find the margins of the tumor

Surgeons have to walk a fine line when operating on cancer. Removing too much tissue can impair function. If too little is removed, cancer may remain and spread again, requiring further surgery.

“We don’t want to do that. We want it to be a one-shot,” said Dr. Gadi Marom of Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem, one of the clinicians involved in the study who specializes in minimally invasive robotic surgery for patients with gastric and esophageal diseases.

This is where sensing technology comes in handy. By converting physical contact into visual information, such as color-coded maps showing softer and harder areas, surgeons can regain the functional equivalent of touch.

“With the new equipment, we hope to be able to determine the margins around the tumor,” Marom said.

What you feel using light

To that end, the team’s engineers are looking to the light.

The probe they are developing has a fiber optic cable embedded in a soft, flexible tip. When pressed against tissue, the tip deforms, changing the light passing through the fiber.

“As the silicone dome presses against the soft tissue, we are able to map both the direction and magnitude of the applied force,” explains Dr. Georgios Violakis of the Hellenic Mediterranean University in Heraklion, Crete.

Small changes in light intensity and wavelength are translated into information about tissue stiffness.

In the lab, partners are contributing to the overall system, and the team has already built and calibrated early versions of the soft membrane and light-based sensors.

Queen Mary University of London (UK) is supporting the membrane design and refinement, Fraunhofer Institute (Germany) is supporting the development of the functional film, and Bendable (Greece), Tech Hive Lab (Greece) and the University of Essex (UK) are developing the software needed to visualize the stiffness and tactile maps.

The prototype will be validated in clinical testing before being used on patients.

Each fiber optic cable is about as wide as a human hair. Similar sensing techniques have been used for years to detect small movements in large structures such as aircraft, skyscrapers, and nuclear reactors. Here it is applied on a much smaller scale to detect subtle differences in human tissues.

Professor Panagiotis Poligerinos, a soft robotics researcher at the Mediterranean University of Greece, said: “To access the internal organs of an anesthetized patient, the device needs to be highly precise and high-resolution.”

“While this could have been possible earlier, the technology was much more expensive and less accurate, making it impractical for clinical use.”

Bring touch to robots

As surgery becomes increasingly robotic, the loss of tactile feedback becomes more pressing, making tactile restoration even more important.

“When operating a robot, you get the benefit of 3D vision,” Marom says. “And you don’t have to stand for the entire procedure.” This is important for long procedures, such as removing a patient’s esophagus, which can last up to eight hours.

Robotic surgery also offers new possibilities. Marom hopes that surgeons may eventually be able to remove small esophageal tumors in carefully selected cases without having to remove the entire organ.

But there are also drawbacks.

“With robotic surgery, there is very little tactile feedback,” Arezzo says. “That’s why this work is so important.”

Both surgeons believe that robotics will continue to expand in the operating room, but only if surgeons are given better sensory information.

“I think sooner or later the majority of surgeries will be done robotically,” Arezzo said.

For Marom, working closely with engineers was essential. “I’m exposed to soft robotics and a lot of new technologies,” he said. “I can see how new equipment is developed.”

“The bottom line is that we will be able to provide better care to our patients,” he added.

The research for this article was funded by the EU’s Horizon program. The views of the interviewees do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

This article was originally published in Horizon, EU Research and Innovation Magazine.

Detailed information

Source link