Physicists have put thousands of atoms into the “Schrödinger’s cat” state, breaking the record for the most macroscopic object observed in a quantum state.

In a new study, researchers observed that nanoparticles made of 7,000 sodium atoms act as cohesive waves, pushing the strange world of quantum mechanics to new limits. Based on this work, future experiments could eventually place biomolecules in quantum states and open new ways to investigate their physical properties.

you may like

here and there

In the quantum realm, particles can be everywhere. This strange phenomenon is known as quantum superposition.

Quantum physicist Erwin Schrödinger likened this to putting a cat inside a sealed box containing a vial of poison that is set to release radioactive material when it decays. This means that the cat can be killed at any time after the box is sealed. This leaves the cat in both a dead and alive state. It is only when you open the box and observe the cat that the superposition breaks down and defines whether the cat is dead or alive.

Incredibly, this is how particles behave at the quantum scale. They can be in multiple places at the same time and act as both particles and waves until they are observed.

This strange world raises the question: where is the boundary between the quantum world and the world we observe every day? At what point do particles start behaving like waves?

The reason we don’t see quantum superpositions around us is because of a process called decoherence. When something in a quantum superposition interacts with its environment, it decoheses and is no longer here or there. Instead, they are forced into one place. Larger objects cannot maintain quantum superposition because they are constantly interacting with their environment. So the real challenge when trying to observe larger particles acting as waves is to separate them so that they remain in a coherent quantum superposition.

looking for interference

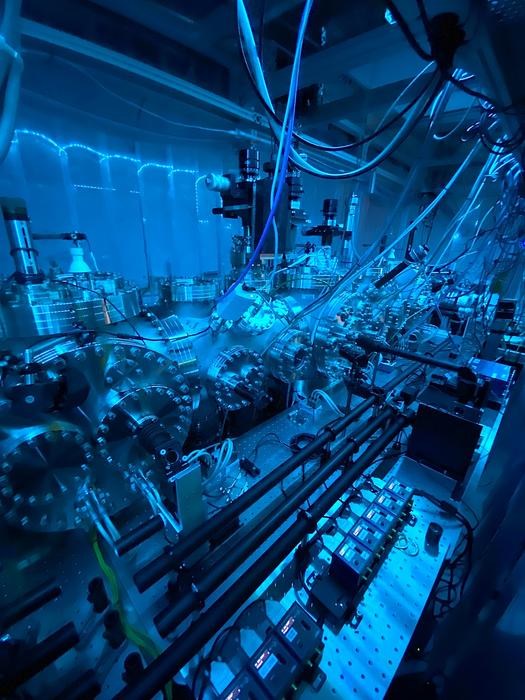

For the new study, Pedalino tried to observe large nanoparticles of sodium in quantum superposition. To do this, he and his team converted several grams of sodium into a beam of nanoparticles and directed it through a narrow slit.

you may like

If the sodium nanoparticles are in a quantum superposition state, it means that they spread out like a wave after passing through the slit. This produces an interference pattern. But if the sodium decohered and started behaving like a normal particle, it would pass straight through the slit and the team would see a flat line.

“For two years, I was looking at flatlining,” Pedalino said. “I tried to look at the interference pattern, but I got a flat line. After all, a flat line is not conclusive, so it’s not very useful.”

Eventually, the single line seen on the detector broadened into an unmistakable interference pattern, meaning the sodium nanoparticles behaved both as particles and waves.

“That moment was unbelievable,” Pedalino said. “It was already late at night, so I called my professor. He came back to the lab and continued measuring until 3 a.m., when the sodium ran out.”

The research team determined that the sodium nanoparticle’s “macroscopicity” (a measure of how far a quantum object is pushed into the classical world) was 15.5, beating the previous record for macroscopicity by an order of magnitude.

This discovery opens the door to future experiments where scientists can realistically observe biological materials such as viruses and proteins in quantum superposition. This experiment represents a major step forward, bringing this strange quantum phenomenon tantalizingly close to the real world.

brandon specter

Space and physics editor

No one wants to think about a dead cat. So why has Schrödinger’s thought experiment endured so long in physics? Partly because superposition reveals a major crack in our understanding of the universe.

Decades of experimentation have shown that while small particles follow one set of rules (quantum mechanics), large structures such as stars, galaxies, and – yes – your cat – follow another set of rules (Einstein’s theory of relativity). Scientists have long been trying to reconcile these two sets of rules into a “theory of everything,” but so far without success. However, recent research suggests that fine-tuning the Schrödinger equation could lead to a solution.

Source link