In recent years, several satellites have made unexplained and disorderly approaches to commercial and military space objects. If a satellite is traveling close to another satellite in orbit around the Earth, how close does it have to be to be “too close”?

In December 2025, a satellite launched from China’s Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center came within 200 meters of SpaceX’s Starlink satellite, which was orbiting at an altitude of 560 kilometers. No collision occurred, but there was no coordination between operators and no shared trajectory data, so the approach could have been avoided. This is not an isolated incident. In mid-2024, another state’s satellite moved within a kilometer of India’s military mapping satellite. Indian authorities described this as an aggressive move to test their capabilities.

In recent years, Russia’s Luchi “Inspector” satellites have continued a pattern of unexplained and chaotic approaches to Western satellites in geostationary orbit. These incidents highlight unresolved and pressing issues for the broader space community. That is, if a satellite is sailing close to another satellite in orbit, how close is too close?

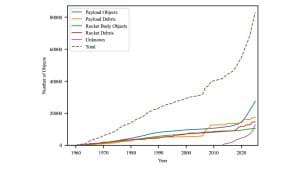

2025 saw record levels of space activity, with more than 300 successful launches and an estimated 4,500 payloads reaching orbit. Earth’s orbit is becoming increasingly crowded, with 13,000 operational satellites sharing space alongside an estimated 141 million debris objects. This growth in in-orbit population coincides with the increasing sophistication of satellites, especially in rendezvous and close operations (RPO). An RPO is an orbital maneuver in which two spacecraft arrive at the same orbit and come into close proximity, followed by a possible docking.

Despite these technological developments, the governance framework governing human activities in space remains frustratingly vague about what constitutes acceptable behavior in this crowded environment. This discussion considers the issues arising from satellites operating in close proximity, particularly non-consensual RPO missions, and asks when operations cross the line from legitimate activity to interference with other space users.

Operations with and without consent

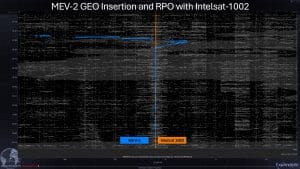

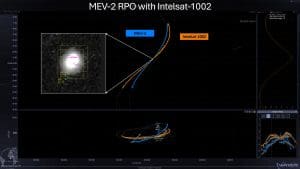

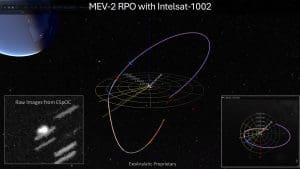

RPO activities can be broadly classified into two categories. Consensus-based operations involve a high degree of coordination based on clear goals and mutual agreement. In 2020, Northrop Grumman’s MEV-1 became the first commercial spacecraft to remotely and robotically dock with another spacecraft in geostationary orbit, extending the operational life of Intelsat 901 through a transparently publicized mission with regulatory approval.

China’s Shijian-21 demonstrated similar technological capabilities in 2022, docking with the defunct Beidou-2 G2 satellite and towing it to graveyard orbit, but without the high degree of transparency that characterizes MEV missions. More recently, RPO has become the centerpiece of Operation Olympic Defender, a multinational coalition coordinating space defense operations between the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, France, Germany, and New Zealand.

Non-consensual operations can be defined as the approach of one satellite to another without notice or declaration of intent. Russia’s Luchi satellite exemplifies this concern. In September 2018, the French defense minister accused the Ruche Olymp spacecraft of espionage after it approached the military communications satellite Athena Fidus.

Luch-2 recently approached various commercial and military satellites in geostationary orbit. Russia describes these as “surveillance” satellites, but a lack of transparency about their mission and purpose turns a potentially legitimate technological development into an act that breeds suspicion and hostility.

The tension between operational transparency and the need to ensure the protection of information for national security creates dangerous unpredictability. If states and commercial actors do not communicate their intentions, uncertainty will increase international tensions and instability.

Why “close” defies a simple definition

To answer the question, “How close is too close?”, a simple numerical threshold would seem to provide attractive certainty. For example, a 10 km radius around each incoming satellite is considered “too close.” Unfortunately, orbital mechanics further complicates this proposition.

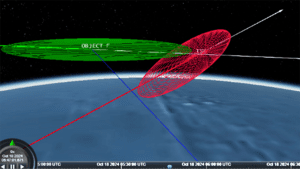

Space Situational Awareness (SSA) providers use radar and optical telescopes to track objects and generate conjunction data messages (CDMs) that predict potential collisions. However, tracking data contains inherent uncertainties that increase over time since the last observation. Orbit determination generates an uncertainty ellipsoid. These are the three-dimensional areas where objects are most likely to reside. If the ellipsoids intersect, the operator measures the “miss distance” to determine the risk of collision.

These calculations do not take into account the physical dimensions of the satellite, so the relative velocity must be taken into account. A 1 km approach at low speed can pose a greater risk to the satellite than a 5 km approach at high speed. This complexity determines how operators define risk thresholds. A study by the Space Data Association found that geostationary orbit operators use miss distance thresholds ranging from 1 to 15 km, while low Earth orbit operators range from 100 m to 1 km, with many relying on collision probability calculations.

Tracking quality depends on altitude and object size. While geostationary orbit benefits from stable optical tracking, low-Earth orbit relies on radar, which is complicated by atmospheric drag, especially for small objects. As mega-constellations proliferate, so do conjunction alerts, with 1,500 CDMs issued in the first few weeks of 2026, more than 80% of which involve low-Earth orbit objects.

Simple boundaries provide only a partial solution because trajectories, risk tolerances, and evaluation strategies differ. Breaking conceptual boundaries is only a problem if there is hostile intent, and intent is not easy to determine.

The question of intent and the dual-use dilemma

The majority of melee operations are routine, necessary and cooperative. Geostationary satellites drift for several kilometers while maintaining their station. Atmospheric drag causes unpredictable convergence in low Earth orbit. However, distinguishing between intentional and malfunctioning operations requires careful analysis of controlled relative movements, planned operational sequences, and stable position maintenance.

These technical indicators can identify behavior, but not motivation. Ground systems track the satellite’s behavior, but depending on the orbital regime and ground capabilities, this is rarely permanent tracking. Additionally, it may be difficult to distinguish between onboard failures, operator decisions, or mission objectives. The most reliable indicators of benign intentions remain advance notice and transparent communication, which is exactly what distinguishes MEV missions from Operation Olympic Defender and Luchi operations.

The technical capabilities of useful commercial RPO are functionally identical to those of adversarial counterspace operations, and this is the fundamental problem. The robotic arm can serve or disable the satellite. Optical sensors can inspect for damage and gather information about vulnerabilities. This dual-use reality means intent, not ability, becomes the key differentiator.

This challenge highlights critical gaps in governance. Without mandatory transparency requirements and established communication mechanisms, legitimate RPO functionality becomes questionable, especially among geopolitical adversaries. Observers cannot distinguish between countries that are developing legitimate capabilities and those that are rehearsing hostile operations. This creates a spiral of suspicion where even benign activities are viewed with hostility.

Addressing governance gaps

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which was drafted before RPO technology existed, provides no details about notification of close operations or mechanisms for distinguishing between commercial and defense operations. The principle of “due consideration” in Article IX provides basic guidance, but it is only enforced by national regulators. Industry associations such as CONFERS (Consortium for the Execution of Rendezvous and Service Operations) are developing best practices. Although they are essential to shaping behavior, they are advisory in nature and non-binding.

Practical transparency measures could transform abstract “due consideration” into concrete norms. This includes steps such as mandatory notification when a satellite maneuvers within specified distances, advance sharing of orbital parameters and operational schedules, and protocols for declaring mission intent. Ultimately, even developing norms around the concept of “innocuous passage” derived from maritime operations may help distinguish temporary approaches from provocative, long-term tailgating.

An enforceable treaty would mandate these requirements and create a presumption of hostility for unannounced operations. Given current geopolitical tensions and legitimate operational security concerns, this is unlikely to happen anytime soon. Countries are reluctant to reveal the capabilities of their national security satellites, which conflicts with the need for transparency for trust-building and verification. Whether norms emerge through UN negotiations, industry standards, or gradual practices, the current ad hoc approach, where close approaches breed mistrust, is unsustainable.

move forward

Space surveillance capabilities continue to improve, which reduces measurement uncertainties. However, despite advances in tracking, operators’ intentions remain subject to geopolitical speculation and hostile suspicions. Without clear mission disclosure and transparency, determining “how close or too close” requires a case-by-case assessment that combines technical data and an assessment of strategic intent. Commercial SSA providers have proven important, enabling transparency and public debate about acceptable orbital behavior that was previously limited to governments.

Industry collaboration to develop concrete codes of conduct is an important first step towards operational ‘rules of the road’. This will ultimately translate abstract proximity issues into actionable requirements for all space users to demonstrate due consideration, promote transparency, and curb inflammatory activities. Broad compliance will highlight malicious actors while distinguishing between legitimate services and hostile tails.

In the current climate of geopolitical instability, an orbital environment where every close encounter arouses suspicion is not in anyone’s interest. Moving forward, all space stakeholders must embrace more transparent and collaborative orbital operations. It is inevitable that technology will continue to advance faster than governance can adapt. The space community must strive to establish transparency measures and codes of conduct that allow RPO technology to fulfill its sustainability promise, rather than becoming a new vector of conflict.

Please note: This is a commercial profile

This article will be published in an upcoming issue of Special Focus Publication.

Source link