Milestone: Discovering the principle of inheritance

Dates: February 8 and March 8, 1865

Location: Brno, now Czech Republic

People: Gregor Mendel

On a cold February day, the Augustinian monk described his experiments in breeding garden varieties of plants, which gave rise to the modern field of genetics.

Gregor Mendel was an Austrian priest who spent eight years cultivating and hybridizing more than 28,000 pea plants (Pisum sativum) in the garden of the Monastery of St. Thomas in Brno (formerly known as Brünn), painstakingly recording the details of the plants’ descendants.

Mendel was actively discouraged from continuing his research. According to a letter from Abbot Cyril Knapp to Mendel in 1859, his bishop chuckled whenever Mendel talked about his scientific experiments.

you may like

“He asked if I thought so. [sic] It looks like someone as intelligent as you is trudging through a pea field, exploring the proclivities of sprouting peas. He suggested that pea breeding was a less curious subject than, say, the writings of the Church Fathers or the doctrine of grace. Dear Brother Mendel, I also sympathize with your research. [sic]We cannot allow the monastery to become the laughing stock of the diocese. ”

However, Mendel was undaunted by his research, not because of his deep-rooted interest in plants, but because he wanted to uncover the principles of heredity.

There were several reasons why he chose to study this humble legume. First, legumes reproduced quickly and well both in pots and in the ground, according to an 1866 monograph he wrote about his research. Second, the hybrid was fully fertile, as it appeared to have distinct characteristics that could be passed on to offspring, such as pink, white, and red flowers.

Finally, he writes, “If an accidental pregnancy with foreign pollen occurred during the experiment and was not recognized, it would lead to completely erroneous conclusions.”

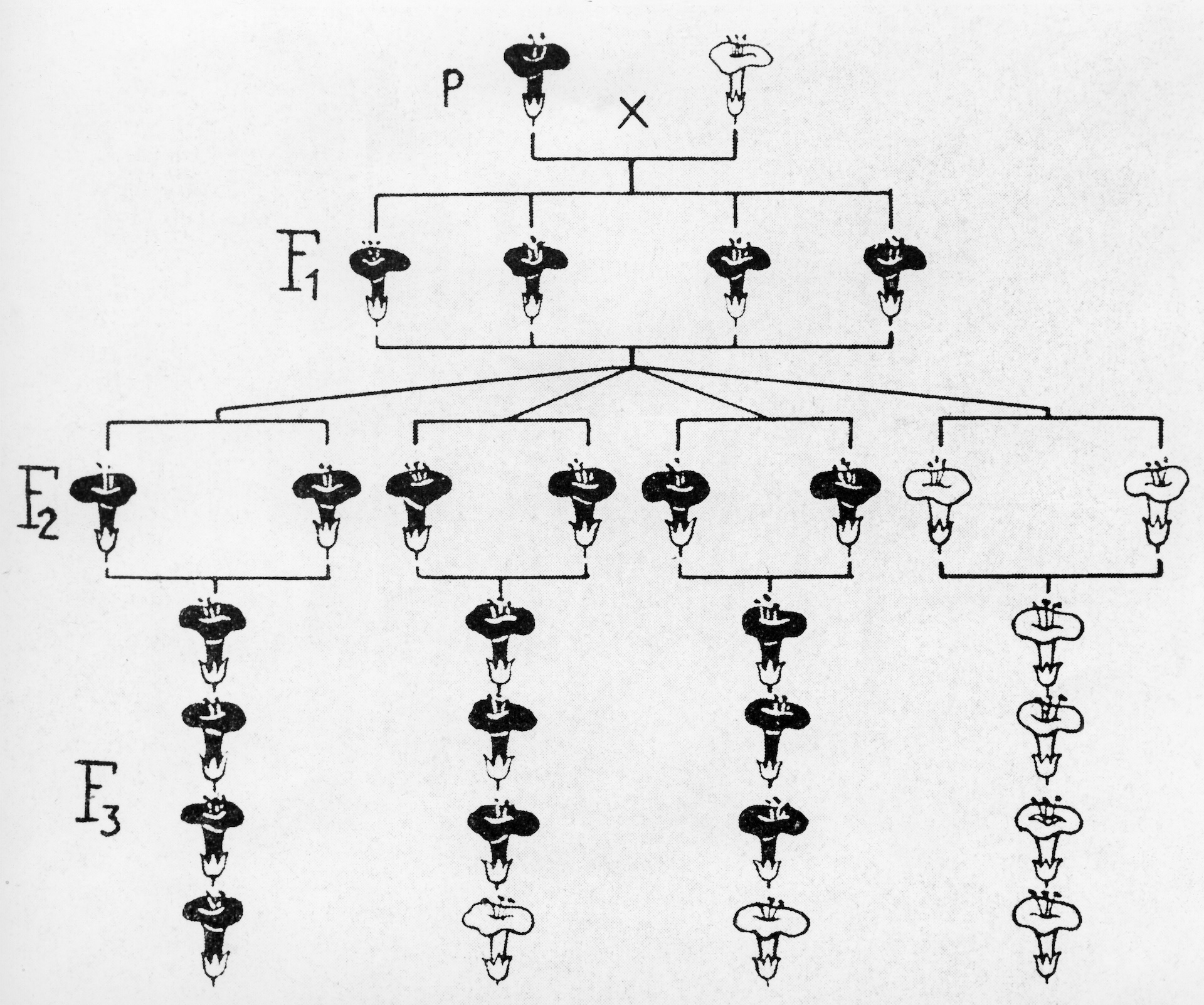

He identified several traits to track, such as the color of peas and their pods, flower location, and stem length, and then crossed them with different traits. They then allowed each different type of plant to “self-propagate” for two years, showing that the traits continued to be passed on to their offspring.

The plants were then crossed and the resulting hybrids were crossed. He painstakingly compiled all the ways in which traits are inherited and labeled the different traits from each parent with simple labels such as Aa, Bb, and Cc.

By analyzing the mathematical patterns of each subsequent generation, he deduced the basic principles of inheritance. First, he noted that some traits are transmitted in discrete units, or “particles.” If you cross a green pea plant with a yellow pea plant, you will not get yellow-green offspring, but green or yellow ones.

you may like

He also concluded that some traits are inherited in a “dominant” pattern. For example, if a plant that has been bred over many generations to have only smooth seeds is crossed with a plant that has wrinkled seeds, the offspring will always have smooth seeds.

When Mendel bred hybrids, he noticed something strange. Most plants appear smooth, but about a quarter appear wrinkled. He speculated that the wrinkled trait was inherited in a rather “recessive” manner, and that the trait actually came from the grandfather plant generation.

Mendel was not satisfied with studying one “particle” at a time. He also crossed plants with two different traits and learned that each trait was transmitted separately. This is now known as the principle of separation.

Mendel’s research was not recognized during his lifetime. Although Mendel is best known as the “father of genetics,” the term “genetics” was not coined until the early 1900s. It was at this time that British biologist William Bateson rediscovered Mendel’s forgotten work and recognized its importance.

Soon after, some argued that Mendel’s data were “too good to be true” and that Mendel must have fabricated his results. A 2020 study put an end to that idea and showed that his results were actually what you expected, given the seeds available at the time, what Mendel knew, and how seeds were classified at the time.

Decades later, research would reveal that heredity was not as simple as Mendel’s pea plant suggested. Some genes are inherited in a sex-related manner, while other traits are imperfectly “penetrant” and are not always expressed in the same way. And in early 2026, research reveals that some disease-causing genes believed to be dominant are not working the way we thought, potentially calling into question some of the basic tenets of Mendelian inheritance.

Source link