Research shows that wildfires on Alaska’s North Slope are occurring more frequently and are more severe now than at any time in the past 3,000 years.

The discovery is based on satellite data as well as soil taken from peatlands that contains ancient charcoal lumps and other signs of wildfires. The researchers say thawing permafrost and tundra “shrubification” are increasing fires, forming a new wildfire regime that is likely to intensify as global temperatures continue to rise.

you may like

Researchers had previously documented an increase in wildfires on Alaska’s North Slope and other parts of the Arctic over recent decades, but the new study contextualized those reports by looking at wildfires over the past several thousand years.

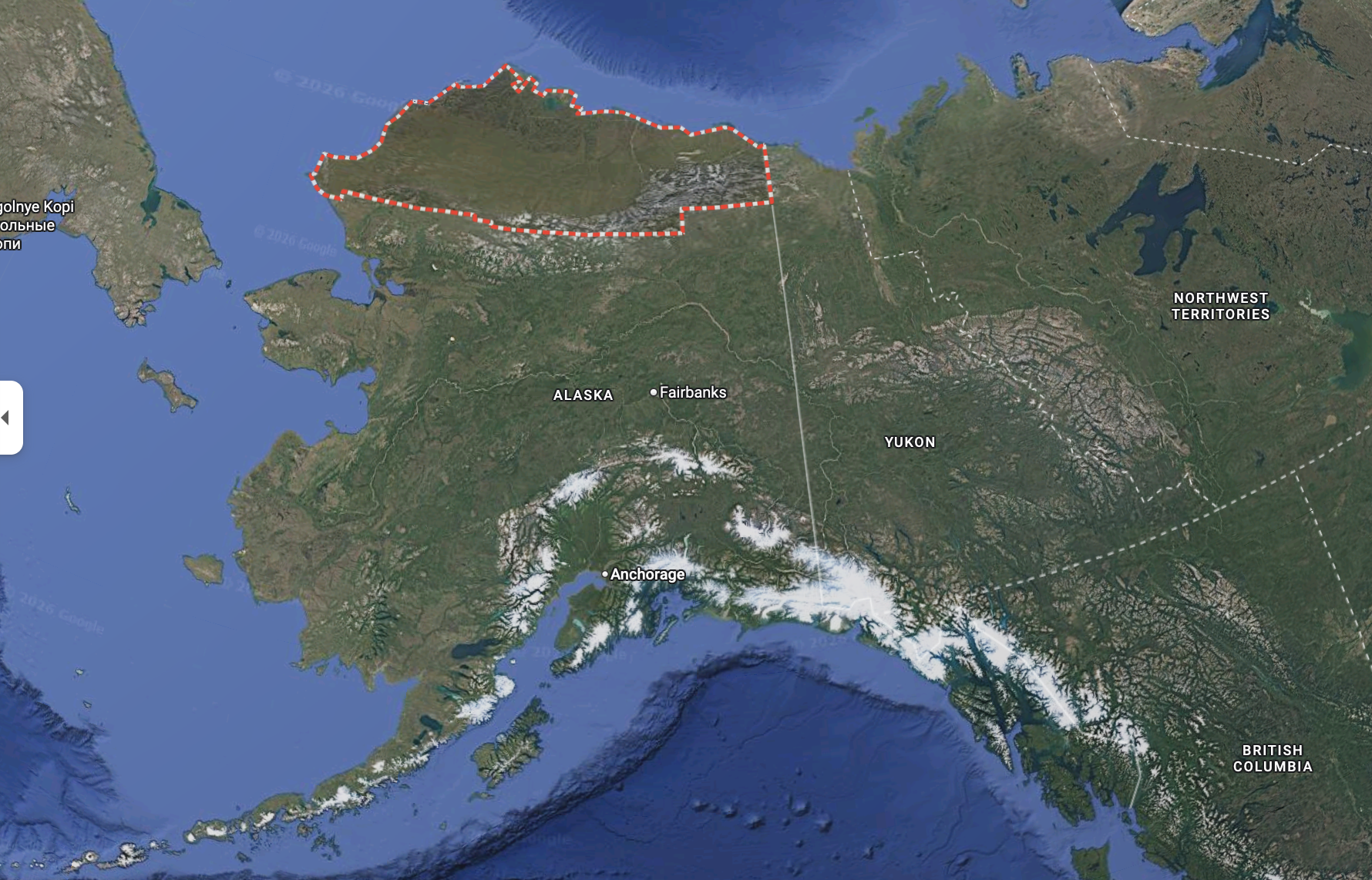

The study, published Nov. 10, 2025, in the journal Biogeosciences, reveals that the current peak in wildfire activity in northern Alaska began in the mid-20th century and significantly exceeds wildfire activity recorded as charcoal in local peatlands since around 1000 BC. Global warming is behind the increase, the authors say, as rising temperatures create drier conditions on land and moisture in the atmosphere, increasing the risk of lightning strikes, a major ignition source. Alaska.

Soil samples for the study were collected from nine peatlands located between the Brooks Range and the Arctic Ocean. Many of these peatlands are covered with small shrubs and sphagnum moss (also known as peat moss), which has only recently become widespread on Alaska’s northern slopes, where it has replaced grass-forming sedges such as Eriophorum vagitum. Sphagnum moss can absorb moisture from the air, which is why it can grow despite dry conditions, Ferdian said. Sedges, on the other hand, require access to moisture in the soil to survive.

The sample was a core about 1.6 feet (0.5 meters) long that contained the past 3,000 years of time. The researchers analyzed the samples to reconstruct changes in vegetation, soil moisture, and wildfire activity over time. Specifically, they tested for pollen and other plant debris. Shards of charcoal. And small, single-celled organisms called testate amoeba are good indicators of water table levels.

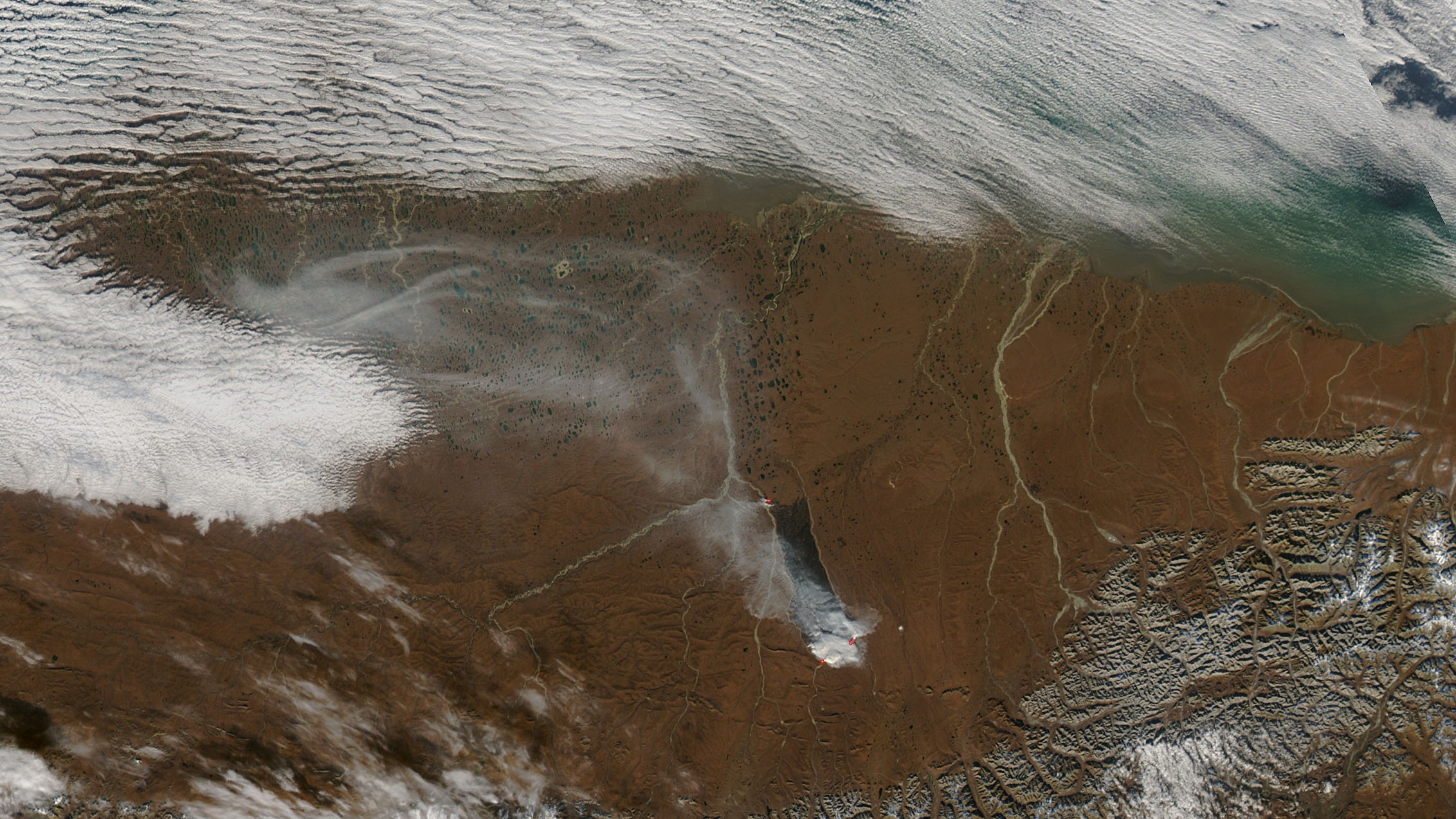

The researchers also analyzed satellite images of wildfires in the northern Brooks Range from 1969 to 2023. When they combined these images with charcoal data to reconstruct fire frequency and severity, they found large discrepancies in the 2000s. Satellites detected a large fire at the time, but evidence of charcoal was minimal.

One explanation is that these fires were hotter than 930 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees Celsius), Ferdian said. Above this temperature, the charcoal turns into ash. If so, the discrepancy in data over the past 20 years suggests that very intense fires have increased, she said.

Overall, the results showed that soil moisture has declined dramatically since around 1950 due to accelerated permafrost thaw and surface water sinking underground. Plants that rely on shallow soil moisture, such as sedges and certain mosses, have been replaced by shrubs, especially those in the heather family (Ericaceae) and sphagnum moss, leading to an explosion in plant fuels for wildfires.

Combined with rising temperatures and lightning strikes, these effects have caused the most severe wildfire activity in the past 3,000 years, Ferdian said.

Alaska’s North Slope is likely a model for what’s happening throughout the Arctic tundra ecosystem, Ferdian added, and wildfires are expected to get worse if warming continues.

“Warmer temperatures increase shrub cover and flammable biomass, which increases fires,” she says. “Fires will continue to become more frequent and severe.”

Article source: Feurdean, A., Fulweber, R., Diacnu, A., Swindles, GT, and Gałka, M. (2025). Fire activity in the Arctic tundra has exceeded late Holocene levels due to increasing aridity and shrub expansion. Biogeosciences, 22(21), 6651–6667. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-22-6651-2025

Source link