An award-winning team of scientists has successfully recreated cosmic processes in a laboratory environment and confirmed phenomena that explain the formation of stars and planets. Editor Georgie Purcell spoke to one of the lead researchers, Hantao Ji, to find out more.

Imagine being able to watch stars and planets form before your eyes. After decades of research, scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) and Princeton University have succeeded in accomplishing just that.

For more than two decades, PPPL’s Magnetorotational Instability (MRI) experiment has studied how swirling matter forms stars, planets, and supermassive black holes. In a recent discovery that won the prestigious John Dawson Prize in plasma physics, a research team has formally confirmed a phenomenon called MRI that explains the formation of planets and stars, and the falling of matter into neutron stars and black holes.

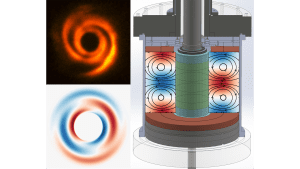

The experiment consists of understanding and reproducing an MRI process that involves an accretion disk of matter swirling in a wobbling universe in a very specific way. This process causes turbulence that spirals matter inward, eventually forming giant objects in space. This is only possible due to the presence of plasma and magnetic fields, which combine to create the wobble.

Using experimental ingenuity, theoretical insights, and advanced computational modeling, the team focused their research on MRI-induced nonuniform wobble. The theory that this kind of wobble could form planets and stars has long been floated, but it has never been confirmed in a real-world environment. For the first time, the research team studied it theoretically and recreated the process in a laboratory setting.

To learn more about the experiment, the challenges encountered along the way, and the significance of the discovery, Georgie Purcell spoke with Hantao Ji, professor of astrophysical sciences at Princeton University and PPPL fellow.

Could you please elaborate on the background of your research and the main purpose of your experiments?

In astronomy, it is usually difficult to observe and try to understand what is happening far away. Typical research models include theory and numerical simulations. But our work is focused on bringing what’s happening in the sky right in front of our eyes. This is an important new way to conduct research and opens up new possibilities for everyone.

Magnetorotational instability experiments focus on reproducing the process of star formation. To form stars, material must move to the center of the molecular cloud. However, this is not easy because the finite angular momentum prevents movement toward the center. Just as the Earth moves around the Sun, angular momentum prevents the Earth from falling into the Sun. Reaching the center requires a process like magnetorotational instability. The key is not to destroy angular momentum, but to give a large portion (say 99%) of the angular momentum to a small amount of mass (say 1%). 1% of the mass has 100% of the angular momentum, while 99% of the mass has no angular momentum. So 99% of this will move to the center and 1% will stay outside. In this sense, 1% becomes the planet and 99% becomes the sun. In summary, the trick with this MRI is to redistribute. Angular momentum must be transferred from the substance that wants to go to the center to the substance that does not want to go to the center.

To achieve this movement, a magnetic field and a plasma, an electrically conductive fluid, must be coupled. This experiment used liquid metal instead of plasma. In the lab, we spin liquid metal to create an “accretion disk.” A magnetic field is then applied to trigger the MRI and transfer angular momentum from one part of the liquid metal to another.

Did anything surprising happen during the experiment?

The main surprise was that things turned out to be much more difficult than I originally thought. I was hoping that MRI would be very easy to perform. We know we can build rotating drums and apply magnetic fields. It’s simple. However, the surprise was in the edge effect.

In an ideal drum, the cylinder would be infinitely long. This is not a problem in theory, as the problem can be theorized by assuming that the cylinder goes infinitely. However, if you want to reproduce this in a lab environment, space is limited and must be finite. For finite lengths, edge effects become important.

In astrophysics, the same problem is not obvious because when an accretion disk is floating in the sky, it has free boundaries because gravity helps bind matter. Unfortunately, labs require caps to prevent liquid metal from falling. The cap is the problem.

We need to rotate liquid metal, but that rotation is not the rotation of a solid. We need differential rotation, faster on the inside and slower on the outside. Much like Venus rotates around the Sun much faster than Earth. This is easy to achieve because different rotations are possible in liquids. But a solid cap cannot have different angular velocities at different radii. The entire cap should only rotate at one speed. This does not match the differential rotation of liquid metal and is problematic. It took 20 years to overcome this mechanical challenge.

Why such a long process?

That’s mainly because I realized that my first theory didn’t work, I had to figure out why it didn’t work, and devise a solution to make it right. Next, we had to test our new ideas to make sure they worked. This was a complex process, with each step taking several years to complete.

Apart from the cap challenge, what other challenges did you face and how did you overcome them?

There are three challenges. Overcoming technical challenges, securing resources, and battling inner doubts.

On the technical side, we are lucky to have a good team. We originally nominated a team of 20 people for the John Dawson Award, but had to narrow it down to five. Over the past 20 years, we have built a community of students and visiting scientists. They have worked with us and made significant contributions to the project. The expertise of our team members and community helped us overcome the technical challenges we faced.

Financially, we had to send numerous funding proposals to funding agencies: the National Science Foundation (NSF), NASA, and the U.S. Department of Energy for support. Although these proposals sometimes failed, we were able to secure funding at each stage. Additionally, the lab here at PPPL is also very supportive.

The third challenge is more psychological. Over the years, we have asked ourselves many times about this experiment. Is it really worth the effort, time, and money? Is it the right question to focus on? We had to make a value judgment and endure.

What does it mean to you to be recognized with the John Dawson Award?

It is a great honor to have our efforts recognized by the scientific community. It is a great honor to be selected to receive this award, as thousands of scientists around the world work day and night in this field. Our group is very small compared to the community as a whole, so we’re really grateful that our contributions have been recognized. After all, small does not mean unimportant, and we hope that there will be some impact from our work.

Winning this award also highlighted the importance of not giving up. You have to be persistent and patient with yourself and your colleagues. It may take some time to see results, but if you give up, you could be missing out on a big opportunity.

Is there a final message you would like to emphasize?

I would like to emphasize the importance of supporting basic research. Basic research allows us to deepen our understanding of the universe and things around us. Each small project is a building block towards tomorrow’s technology. The world of commerce wants results today, but it’s important to support years of research to make tomorrow better.

This article will also be published in the quarterly magazine issue 25.

Source link