In a worst-case scenario, Earth-orbiting satellites could start colliding with each other within three days, setting off a runaway cascade that could render low Earth orbit (LEO) unusable, a new preprint study warns. According to the researchers’ new CRASH Clock, this is 125 days earlier than it would have been in an emergency just seven years ago.

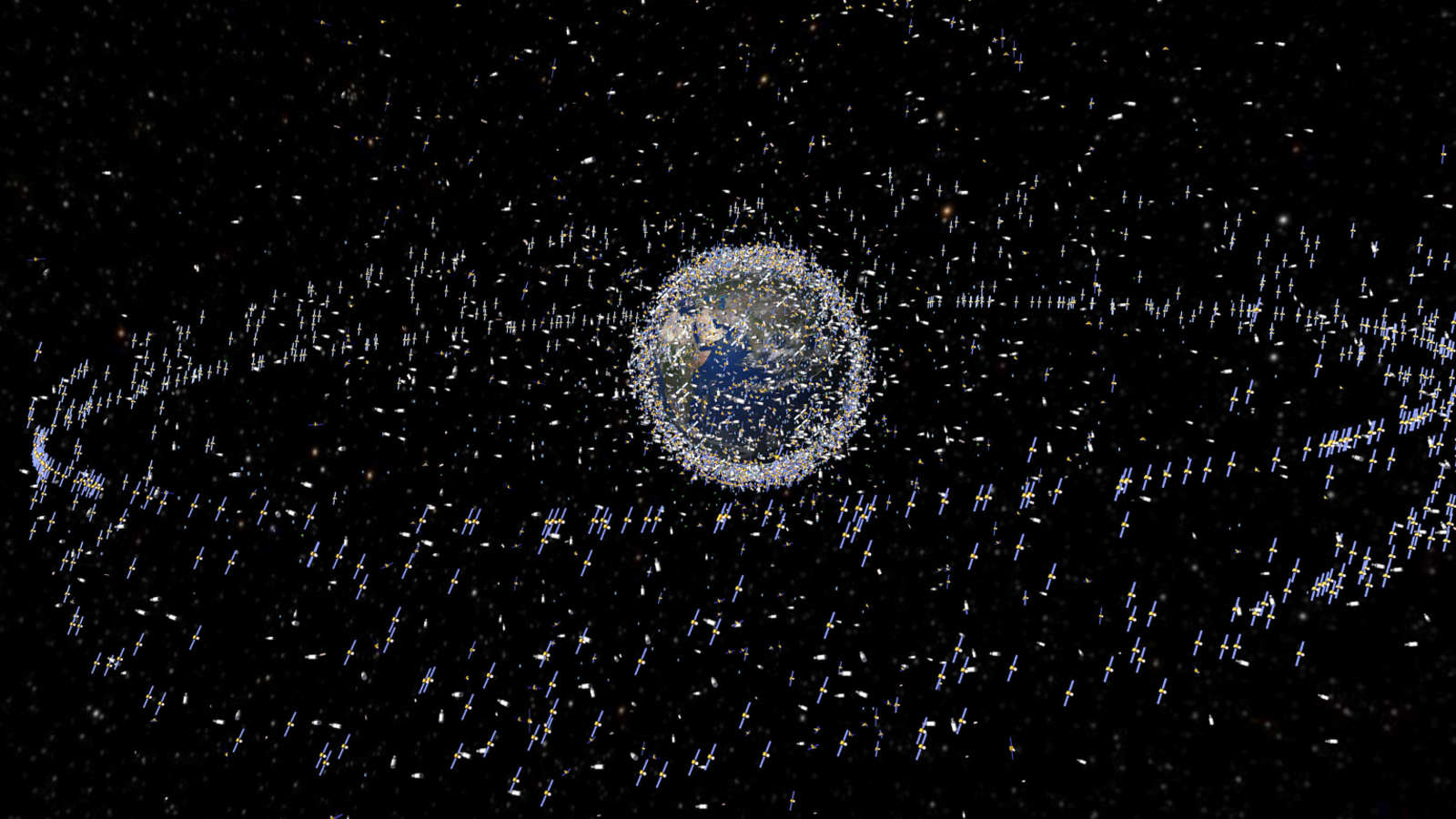

The number of spacecraft orbiting Earth is rapidly increasing thanks to the rise of satellite “megaconsets” such as SpaceX’s Starlink network. As of May 2025, there are at least 11,700 active satellites around Earth, most of them in LEO, or in the atmosphere up to 1,200 miles (2,000 km) above Earth. This represents a 485% increase in LEO’s approximately 2,000 satellites at the end of 2018, before Starlink’s first launch in 2019. And all signs suggest this is just the beginning.

you may like

In a new study uploaded to the preprint server arXiv on December 10, researchers proposed a new way to measure the risk of a collision occurring if all spacecraft were rendered inoperable by one of these worst-case scenarios. The team named this metric the Collision Realization and Serious Hazard (CRASH) Clock. By modeling the distribution of spacecraft in LEO, CRASH Clock shows how long it takes for the first collision to occur. (This is similar to how the infamous “Doomsday Clock” shows how far we are from a hypothetical global Armageddon.)

“The impact clock is a statistical measurement of the expected timescale for an approach that could cause a collision,” study co-author Aaron Boley, an astronomer at the University of British Columbia, told Live Science in an email. “The idea is that it can be used as an environmental indicator to help assess the overall health of an orbital region, while also allowing people to conceptualize how much or how little margin of error there is.”

In a new paper, the researchers calculate that the collision clock by the end of 2025 is approximately 2.8 days, with a 30% chance of a collision occurring within 24 hours of an emergency event that would render the satellite inoperable. This is much shorter than what was predicted on the clock in 2018 (estimated at 128 days) and would have given operators much more time to recover their assets.

These findings have not yet been peer-reviewed, and the research team now believes they slightly overestimated how short the CRASH clock actually was, Boley told Live Science. However, regardless of the exact values, the rate of change in these time frames is what concerns us the most. (New, more reliable values for the CRASH clock may be published later this year.)

“If you look at the difference, [in values] “This was one of the motivations for us to further develop the CRASH clock,” Boley said, adding that the fact that the value has already decreased significantly is as good an “indicator of in-orbit stress” as the CRASH clock itself.

As more satellites are deployed, the value of CRASH clocks is likely to continue to decline further in the coming years. For example, Space News recently reported that there will be 324 orbital launches in 2025, a new record and a 25% increase compared to 2024.

Researchers do not predict exactly how much the CRASH clock will change over the next few years. But they suspect current trends will continue. “Whether the crash clock decreases will depend on the continued approach to industrializing Earth orbit,” Boley said. “If the orbital shell continues to become denser, it could continue to get shorter.”

A “crash clock” scenario would most likely develop due to a major solar storm that could temporarily disrupt satellite systems with large amounts of radiation, study lead author Sara Thiel, an astrophysicist at Princeton University, recently told Live Science’s sister site Space.com. When such an event occurs, “it becomes impossible to estimate where the object will be in the future,” she added.

If a satellite remains offline for longer than the crash clock value, multiple collisions may occur, potentially bringing it dangerously close to the Kessler syndrome threshold. Kessler syndrome is a theoretical scenario in which a cascading collision in a LEO trigger causes an exponential increase in space junk, in which nothing can safely operate.

Researchers are reluctant to predict the timing of this scenario. That’s because there are too many variables surrounding the ensuing satellite collision, and no one really knows at what point Kessler syndrome will be triggered, Boley said. But he warned that if we are not careful, we could soon be “in the early stages” of a series of irreversible conflicts.

Source link