The catastrophic collision that formed the moon and was one of the most significant events in Earth’s early history may have been caused not by a distant invader, but by a brother world growing up right next door, a new study reveals.

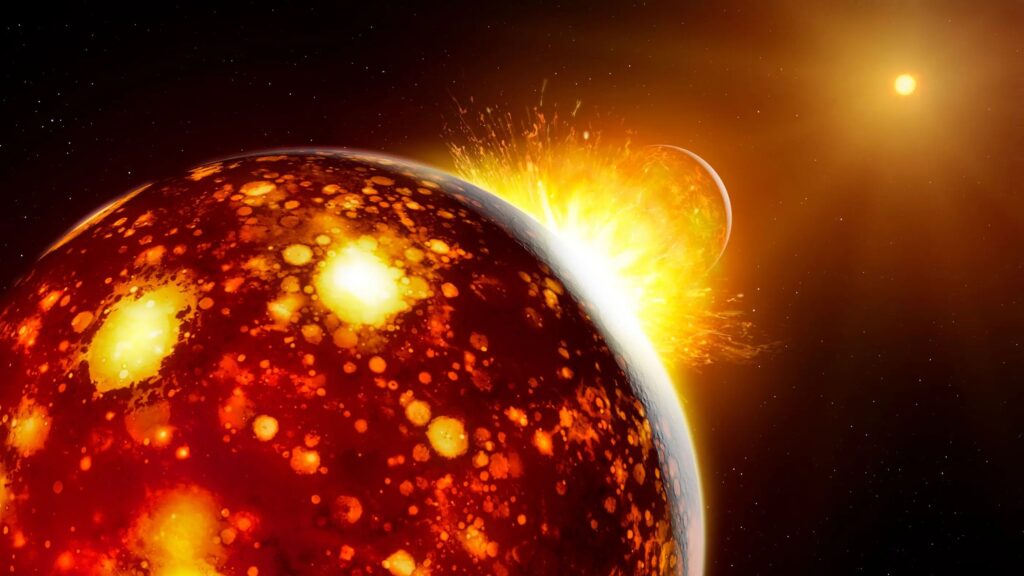

About 4.5 billion years ago, a world the size of Mars collided with young Earth with such great force that it melted vast areas of Earth’s mantle and blasted a disk of molten debris into orbit. Its debris eventually came together to form the moon we know today. Scientists have long favored this “Giant Impact” origin story, but where the long-lost world called Theia came from and what it’s made of remains a mystery.

you may like

violent youth of the planet

During the Sun’s turbulent first 100 million years, the inner solar system was packed with dozens to hundreds of planetary embryos (worlds the size of the Moon to Mars) that frequently collided, merged, or were kicked into new orbits by the gravitational chaos of early planet formation and Jupiter’s massive gravitational pull.

“Theia was one of dozens to hundreds of planetary embryos from which our planet formed,” Hopp said. But lunar samples taken during the Apollo mission show that Earth and the moon are nearly chemically identical, scientists say, making it extremely difficult to pinpoint Theia’s birthplace.

To investigate, Hopf and his colleagues looked for tiny chemical clues left behind by the impact on Earth’s mantle, traces of elements such as iron and molybdenum that would have sunk into Earth’s core if they had been present early in the planet’s formation. Their survival in mantle rocks today suggests that these elements arrived later, perhaps brought by Theia during a giant impact, and therefore contain valuable information about the composition of the lost planet, the researchers say.

clues from the moon

The researchers analyzed six lunar samples taken by the Apollo 12 and 17 missions alongside 15 terrestrial rocks, including specimens from Hawaii’s Kilauea volcano and meteorites recovered in Antarctica and housed in major museum collections.

you may like

Focusing on extremely subtle differences in iron isotopes (different versions of the element), the researchers found in a recent study that they could pinpoint exactly where material formed relative to the Sun. They combined these iron measurements with molybdenum and zirconium isotopic signatures and compared the results to known meteorite compositions to estimate what type of planetary “building blocks” may have formed Theia.

Across hundreds of modeled scenarios, ranging from small impactors to objects nearly half the mass of Earth, the only configuration that successfully reproduced the chemistry of Earth and the moon was the one in which Theia formed in the inner solar system, the study says. Theia was probably a rocky, metal-centered world containing about 5% to 10% of Earth’s mass, the researchers said.

The model also revealed that both proto-Earth and Theia contain material from “unsampled” inner solar system reservoirs, a type of material not present in known meteorite collections. This mysterious component likely formed in a region so close to the Sun that earlier material was swallowed by Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Theia, or failed to survive as a floating object that could become a meteorite.

“It may just be sample bias,” Hopp acknowledged. Samples from Venus or Mercury could one day reveal a larger portion of this missing material, which could ultimately “confirm or reject our conclusions,” he added.

The study reveals that Earth and Theia are likely local siblings, but Hopp said it remains an open question how the giant impact mixed the two worlds so thoroughly that their chemical identity became almost indistinguishable.

Unraveling its mysteries could reveal the final lost chapter of the moon’s violent origin story, and it could be the key to fully understanding how the moon and Earth came to be.

Source link