Four early Anglo-Saxon swords, discovered during a recent archaeological excavation I participated in, each tell a story about how weapons were viewed at the time. There was also the surprising discovery of a child buried with a spear and shield. Was the kid an underage fighter? Or were weapons for them more than just instruments of war?

Weapons have values embedded in them. For example, would a Jedi knight in the Star Wars series have the same nobility if he were armed with a knife instead of a lightsaber? Today, modern militaries fight remotely using missiles and drones, and mechanically with guns and armor. However, in many countries police officers still carry ceremonial swords, and wearing them incorrectly can even reveal you as an impostor.

The excavation that archaeologist Andrew Richardson and I conducted focused on an early medieval cemetery, and our sword was discovered in the grave. Our teams from Lancashire University and Isle Heritage University excavated around 40 graves in total. The discovery can be seen on BBC2’s Digging for Britain.

you may like

One of the swords we found was decorated with a silver pommel (back of the hilt) and a ring fixed to the hilt. It is a beautiful and noble 6th century object housed in a sheath lined with beaver fur. The other sword has a small silver hilt and a wide ribbed gold-plated scabbard, combining two elements from different art styles and different eras into one weapon.

This mixture was also found in the Staffordshire hoard (discovered in 2009), which featured 78 pommel heads and 100 pommel collars, dating from various dates from the 5th to the 7th century AD.

In the Middle Ages, swords and their parts were carefully selected by their owners, and old swords were valued more highly than new ones.

The Old English poem “Beowulf” (probably composed between the 8th and early 11th centuries) describes an old sword (“Aarsweld”), an ancient sword (“Gomelsweed”), and an heirloom (“Ilfelafe”). Similarly, he described “weapons hardened by wounds” as “Weapen wonders heard.”

The Exeter Book, a large collection of poems written down in the 10th century, contains two riddles of the sword (although the text within it may describe earlier attitudes). In Riddle 80, the sword describes itself as “I am a warrior’s companion.” This is an interesting way of saying it, considering the discovery in the 6th century. In each case the hilt rested on the shoulder, and the deceased’s arm appeared to be cradling the weapon.

A similar embrace was also seen at a burial in Dover Buckland, Kent. There were two in Blacknall Field, Wiltshire, and one in West Garth Gardens, Suffolk. However, it is unusual to see four people buried in one cemetery like this, and interestingly, they were found so close together.

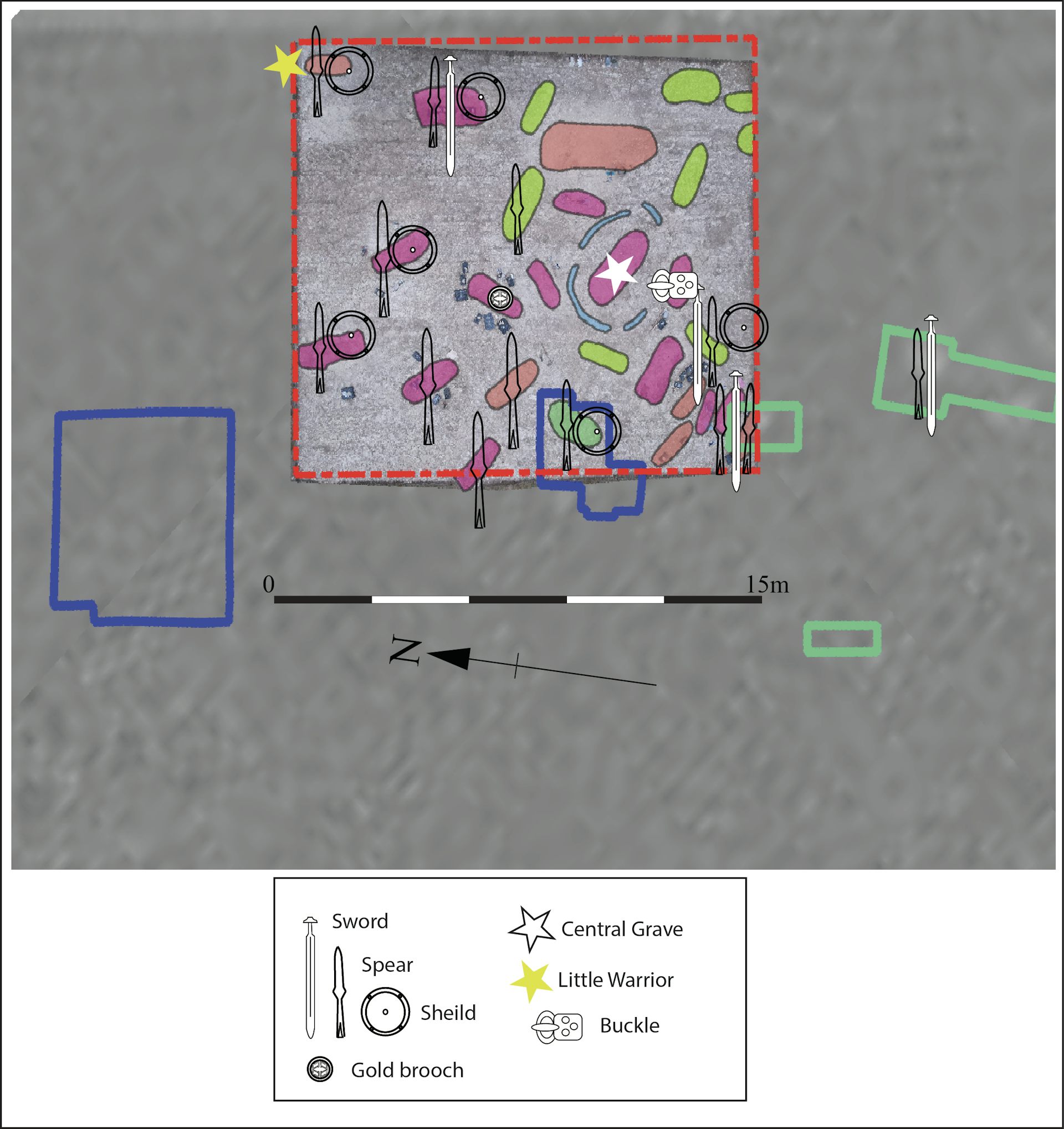

The part of the cemetery we excavated contains several weapon burials placed around deep graves surrounded by a ring ditch. A small mound of earth would have been built over the grave to mark the boundaries of the grave.

you may like

This oldest tomb (the one that the other weapons graves used to mark their location) contained metal artifacts and men without weapons. Weapon graves were popular in both generations from the mid-6th century onwards, so this figure may have been buried before the fashion for dressing the dead with weapons was established. This is probably because during the tumultuous late 5th and early 6th centuries, weapons were highly valued for protecting the living.

The situation was further deepened by the discovery of more graves of children aged 10-12 with spears and shields. Since the child’s spine was curved, it was unlikely that he would be able to use these weapons comfortably.

The second grave of a young child contained a large silver belt buckle. This was probably too big for a 2 or 3 year old boy to wear. Graves with such items are usually of adult males, and large buckles were symbols of office in late Roman and early medieval contexts, such as the fine gold example at Sutton Hoo.

So why were these items found in graves? Recent DNA results point to the importance of relationships, especially within the Y chromosome, which indicates male ancestry.

In West Helsterton, East Yorkshire, DNA tests showed a biological relationship between men buried nearby. Many of these men were armed, some with swords and two spears. Many of the other male graves were placed around heavily armed ancestors.

We are not saying that ancient weapons were purely ceremonial. Dents on shields and wear on bladed weapons speak of training and conflict. The injuries and early deaths seen on skeletons testify to the use of weapons in early medieval societies, and early English poetry speaks as much of grief and loss as heroism.

As Beowulf shows, the display of dead men and their weapons was associated with a sense of loss and anxiety about the future.

The people of Giath built a crematorium for Beowulf and held a funeral for him.

I stacked them up and decorated them until they were square.

Hanging with a helmet and heavy shield

And shining armor as he commanded.

Then his warriors placed him in their midst,

We are mourning a distant, famous and beloved monarch.

The weapons in our graves were physical expressions of strength, masculinity, and the male family, as well as expressions of loss and grief. Ancient, battle-hardened warriors wept and buried their dead with sword-like weapons that told stories.

Spears, shields and buckles found in small graves told what became of these children in the future.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source link