Cuts on dozens of dog skeletons discovered at an archaeological site in Bulgaria suggest that people were eating dog meat 2,500 years ago. It wasn’t just because they had no other choice.

“These sites were rich in livestock, the main source of protein, so there was no need to eat dog meat out of poverty,” Stella Nikolova, a zooarchaeologist at the National Archaeological Institute of the Museum of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and author of a study published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology in December, told Live Science. “Evidence shows that dog meat was associated with some tradition involving communal feasting.”

Eating dog meat (sometimes called sinophagy) is considered taboo in modern European society, but this wasn’t always the case. Historical accounts mention that ancient Greeks sometimes ate dog meat, and archaeological analysis of dog skeletons from Greece confirmed those stories.

you may like

During the Iron Age (5th to 1st century BC), a cultural group known as the Thracians lived northeast of the Greeks in what is now Bulgaria. The Greeks and Romans considered the Thracians to be uncivilized and warlike, and in the mid-1st century AD Thrace became a province of the Roman Empire. Like the Greeks, the Thracians are said to have eaten dog meat.

To investigate the question of whether Thracians ate dogs, Nikolova examined human remains from 10 Iron Age sites across Bulgaria and previously published data. She found that most dogs had medium-sized snouts and medium- to large-sized withers, and were about the same size as modern German shepherds.

But many of the bones showed signs of slaughter, making it clear that dogs are not man’s best friend. “There are a lot of livestock at the scene, so it was most likely kept as a guard dog,” Nikolova said. “I don’t think they were seen as pets in the modern sense.”

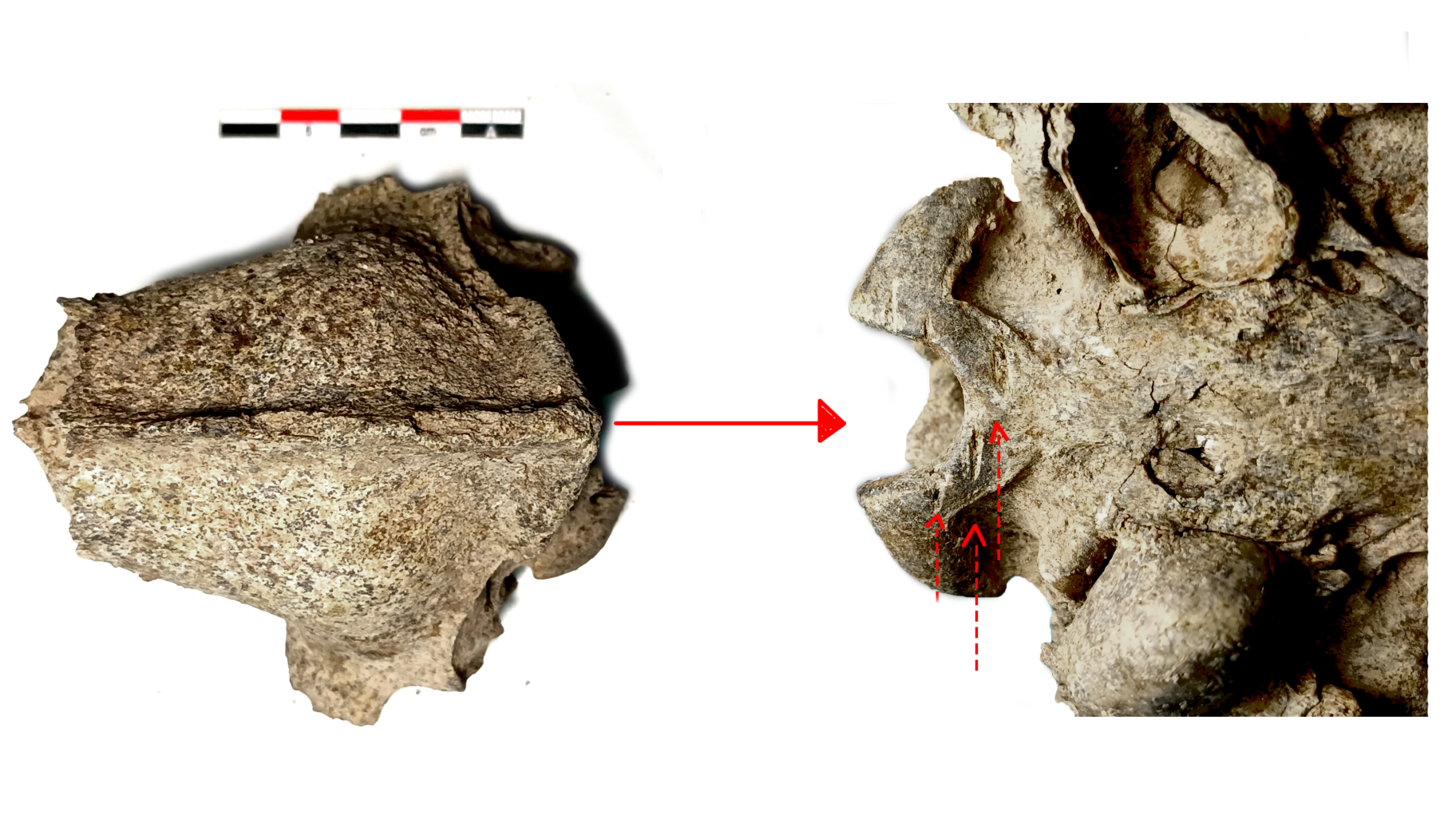

At the site of Emporion Pistilos, an Iron Age trading center in inland Thrace, archaeologists discovered more than 80,000 animal bones, 2% of which were dogs. When Nikolova took a closer look at the Pistilos dog bones, she found that nearly 20% of them had signs of slaughter made with metal tools. The dog’s two lower jaws also had burnt teeth, possibly indicating that someone had burned the animal to remove hair and fur before slaughtering and cooking.

“The highest number of amputations and fragmentations occurs in the area where the musculature is most dense – the upper quarter of the hindlimb,” Nikolova said. “In the case of dogs, you can hardly get any meat, but there are also cuts in the ribs.” The cuts Nikolova found on the dogs followed a similar pattern to the cuts on sheep and cows at the scene, suggesting that all the animals were slaughtered in a similar manner.

Nikolova doesn’t think the Thracians ate dogs as a last resort, since they had many other animals traditionally associated with carnivory, such as pigs, birds, fish, and wild mammals.

In Pistilos, the bones of butchered dogs were found in the remains of feasts and in piles of household garbage, Nikolova said, suggesting that dog meat could have been consumed in a variety of ways. “That is, it was an occasional ‘delicacy,’ tied to a particular tradition but not limited to that title,” she said.

Several other Bulgarian sites examined by Nikolova, as well as sites in Greece and Romania, showed evidence of cutting and burning dog bones, meaning that “the consumption of dog meat cannot be classified as unique to ancient Thrace, but was a practice that occurred with some regularity in the first millennium BC in the northeastern Mediterranean,” Nikolova said in her study.

Nikolova plans to further investigate the role of dogs in pistilos as part of the Corpus Animalium Thracicorum project. She said the dogs slaughtered at Pistilos date back to the early Iron Age, but then people there began burying intact dogs, so she said she wanted to determine whether there had been a change in people’s attitudes over time, making dogs a less acceptable food source.

Nikolova, S. (2025). Dog meat in Late Iron Age Bulgaria: a necessity, a delicacy, or part of a broader cross-cultural tradition? International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.70062

Animal Quiz: Test yourself with these fun animal trivia questions

Source link