Have you ever stopped by a grocery store on your way to a dinner party and grabbed a bottle of wine? Have you grabbed what you saw first, or have you considered the available choices and deliberated where your gifts would like to come from?

People who lived in western Iran 11,000 years ago had the same idea, but in reality they looked a little different. In our latest study, my colleagues and I studied the ruins of the ancient east feast in Asiabu, in the Zagros Mountains, where people gathered for a joint celebration.

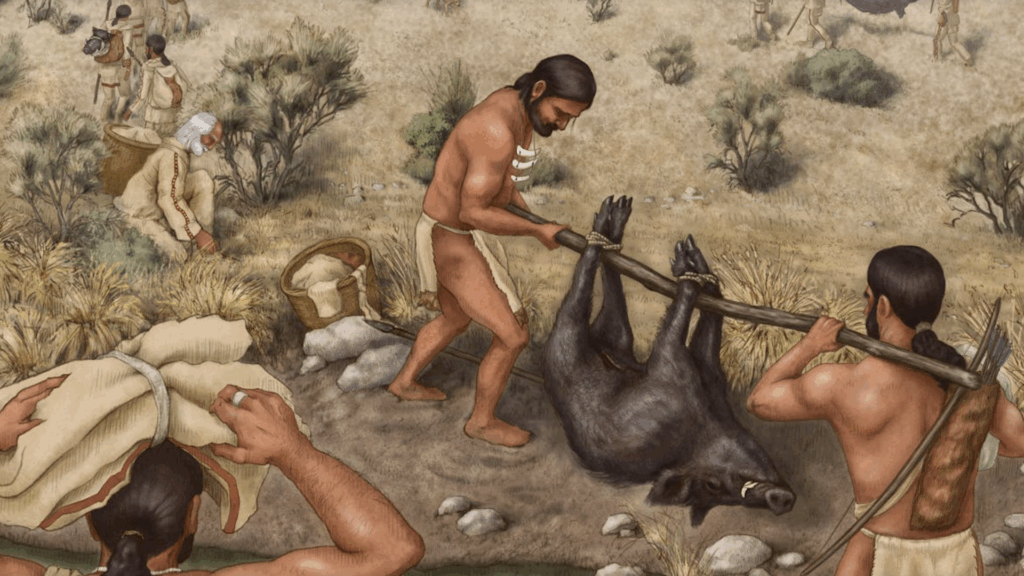

The fairer left behind the skulls of 19 wild boars. They were neatly stuffed together and sealed inside a hole in a round building. The butcher mark on the boar skull indicates that the animals were used for feasts, but up until now we had no idea where the animals came from.

You might like it

By examining the microscopic growth patterns and chemical characteristics within the enamel of five of these boars, we found that at least some were transported to difficult mountainous regions and brought to the site at a considerable distance. Bringing these boars to the east feast – when other boars become available locally, they will make a huge effort.

A big east feast from before the dawn of agriculture

Feasting activities are widely documented in archaeological records from communities that rely primarily on agriculture to generate food surplus. In fact, this theory has been widely debated, but suggests that it may have been a driving force behind the adoption of agriculture.

Evidence after agriculture is abundant from all areas around the world, but pre-farming evidence is more sparse.

The special feature of the Asiab east feast is that it brought together people from a wider range of the region, not just in the early days. The fact that the people who attended this East Feast invested a considerable amount of effort, and that their contributions included elements of geographical symbolism.

Related: “cornhead” skull from Iran was beaten 6, 200 years ago, but no one knows why

Food and Culture

Food and long-standing culinary traditions form an integral part of cultures around the world. This is why holidays, festivals and other socially meaningful events generally include food.

For example, you can’t imagine Passover without Christmas without Christmas meals or without food gifts.

Plus, the food makes a very appreciated gift. The more food is associated with a particular country or location, the better it becomes. For this reason, French cheese, Australian crocodile jerky, and Korean black chicken make good currency in the world of gift gifts.

Just like today, people who lived in the past realized the importance of reciprocity and the place and formulated customs to celebrate them publicly.

For example, at the ancient East Feast of Stonehenge, studies show that people ate pigs brought from a wide range of England. Our new findings provide the first glimpse into similar behaviors in pre-agricultural contexts.

How to read teeth

Did you know that teeth grow like trees? Just like trees and their annual growth rings, teeth deposit a visible layer of enamel and dentin during their growth.

These growth layers track daily patterns of development and changes in dietary intake for specific chemical elements. In our study, we sliced boar teeth from Asiana so that these daily growth layers can be counted under a microscope.

This information was then used to measure the composition of enamel secreted almost weekly intervals. The variation in isotopic ratios we measured suggests that at least some of the wild boars used in the east feast of Asiab came from a considerable distance: perhaps from a trip of at least 70 km, or more than two days.

The most likely explanation is that they were hunted further in the area and transported to the site as a contribution to the east feast.

Reciprocity is at the heart of social interaction. As with today’s thoughtfully chosen bottles of wine, wild boars brought from afar may have helped to commemorate places, events and social ties by giving gifts.

This edited article will be republished from the conversation under a Creative Commons license. Please read the original article.

Source link