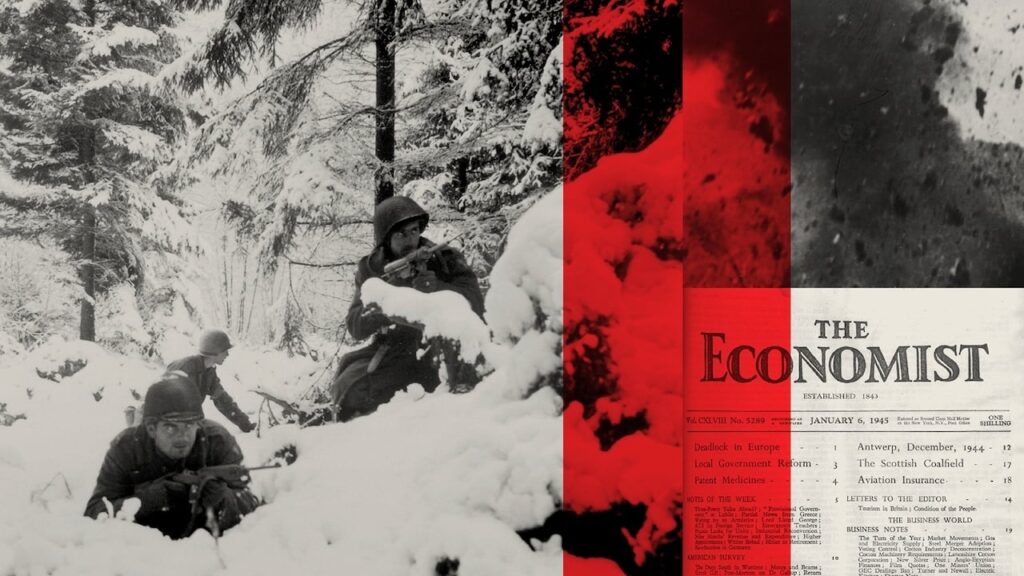

How The Economist reported on the final year of the second world war, week by week

In January 1945, 80 years ago, the second world war was entering its seventh year. Fighting raged in Europe, as Allied armies liberated large parts of France and Belgium from Nazi control. The Red Army was pushing from the Soviet Union into Poland, squeezing German forces from the east. Meanwhile the Allies’ campaign in the Pacific was gathering momentum, and America was planning for an invasion of Japan. The outcome of the war would transform the international balance of power, politics and the global economy in ways that still shape the world.

January 3

By January 6th 1945, when we published our first issue of the year, the conflict in Europe was in its last stages. We wrote that, late in 1944, “it was not only ordinary men and women who said, ‘It will all be over by Christmas.’” But the speed of the Allies’ advance into Nazi-occupied parts of Europe had slowed. Germany’s Rundstedt offensive (now better known as the Battle of the Bulge) had put the Allies on the back foot in Belgium and Luxembourg. The British were still fighting in Greece. Poland’s communists, known as the Lublin Committee, were at loggerheads with the Polish government-in-exile in London over who would control the country.

The mood in Britain was grim. Although the Nazis were still being squeezed on both sides of the continent, The Economist declared “Deadlock in Europe”:

“The year 1945 is opening gloomily for the Allies. Fighting still goes on in Athens. The Lublin Committee has added another twist to the tangled knot of Polish politics by declaring itself the provisional government of Poland. Across the Atlantic, American criticism of Britain and distrust of Russia show but little sign of abating. Militarily, too, the outlook is disappointing. The Rundstedt offensive has been checked, but that it should have succeeded at all grievously contradicts the high hopes of last summer.”

It was not that victory felt distant to Britons—in fact it looked all but assured. But “military deadlock and political disunity” had delayed the Nazis’ defeat. Disagreements over how Germany would be treated after the war were a problem. The Nazis, we wrote, were hoping “that the coalition against them will, after all, collapse”. And a proposal for post-war Germany to cede its industrial heartlands, advanced by France and the Soviet Union, was giving Germans a stronger will to fight on.

Britain had reason to feel glum beyond the battlefield, too. Running a war economy had taken a heavy toll on its people. The Economist had recently received one of the first big releases of statistical data since the beginning of the war (though we explained that “reasons of security still demand that some remain secret until the defeat of both Germany and Japan”). War had transformed the British economy. It wasn’t just that the government had hiked taxes to pay for the war effort. Spending on consumer goods had plummeted, even if fuel and light sold well during the Blitz—as we illustrated in this chart:

“No motor-cars, refrigerators, pianos, vacuum cleaners, tennis or golf balls have been produced since 1942, and only very few radios, bicycles, watches and fountain pens.”

Rumours had swirled in 1944 that Adolf Hitler had died, gone mad or been confined by Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS (the Nazis’ main paramilitary group). But Hitler’s New Year address, we wrote, showed that he was “alive, no more insane than usual, and not dramatically imprisoned”:

“His talk was full of the German myth, the rebuilding of bigger and better German towns, the failure of the bourgeois world and the new dawn of National Socialist principles…He appears to have passed beyond even a remote interference in the strategy of the war and to be now little beyond the focus for the despairing nationalism of the German people.”

Still, with the Nazis being pressed by the Allies in the west and the Soviet Union in the east, the dictator’s appeals to nationalism were ringing hollow. Rather, his message smacked of bluster and desperation. ■

January 10

While the Allies squeezed the Nazis in Europe, American forces in the Pacific put pressure on Japan. It had bombed Pearl Harbour, a naval base in Hawaii, on December 7th 1941, killing nearly 2,500 people. The next day President Franklin Roosevelt went to war in Asia. As 1945 began, America had checked the expansion of Japan’s empire and was making advances in the Philippines, which had been under Japanese occupation since 1941:

“The landing on Luzon, the largest of the Philippine Islands, has begun. Great American forces have already established four bridgeheads, and although tough fighting lies ahead, there can be no doubt that the last phase in the recapture of the Philippines has begun and that the end is in sight.”

The Economist turned next to China. America had been supporting it against Japan since 1940 with loans and weapons. In 1941 it sent military advisers and established air bases on the mainland. It had a strong interest in helping China end Japan’s occupation—not only to weaken Japan, but to strengthen China as a major power that would help enforce peace in Asia after the war.

This was no easy task. China was then run by a patchwork of rival governments. Outside the areas under Japan’s control, some of the country was led by the Kuomintang, a nationalist group led by Chiang Kai-shek, with a base in Chongqing, in central China; another area was controlled by the Communists, led by Mao Zedong, with a stronghold in Yan’an, a city in the north. Japan’s defeat could cause a situation “of the greatest confusion” in China, we wrote. Though the country’s two rival powers had fought alongside each other against the Japanese, they had also “been for some years in a state of actual or latent civil war”.

The civil wars that had broken out in liberated countries in Europe seemed to augur ill for China:

“In face of this situation—a potential Greece of the Far East, on a vaster and even more damaging scale—what policy ought the allies to pursue? China’s allies suffer from this grave disadvantage, that foreign intervention is always unpopular, and interference, if pressed too far, may end in nothing but violent dislike for those who have done the interfering…It is therefore with the utmost patience and tact that the Allies must press on both sides in China the need for unity.”

But unity, we noted, would be hard. Chiang seemed motivated “more by the desire to maintain and reinforce power than by any wish to share power in some new administration with the Communists”. The Communists were determined “to maintain power in their own areas and spread it where they can”. Though we argued that a government of national unity would be best for China, it was hard to see how it was to be “brought into being”. ■

January 17

By the beginning of 1945 most of France had been liberated. The previous August, the Allies had wrested Paris from German control and Charles de Gaulle, who had led a provisional government in exile from London and Algiers, returned to the capital. Occupation had taken its toll. On January 20th 1945, The Economist wrote:

“France has been allowed to drift into a position from which it must be speedily rescued. The population of Paris and of many other towns is shivering from lack of coal; during the first week of this month daily deliveries to Paris averaged little more than 10,000 metric tons, a mere fraction of normal requirements and barely enough to meet the urgent need of hospitals, schools and essential public services.”

Bread was rationed at 13 ounces (370g) a day, and cheese at 0.75 ounces (20g) a week. Even then, there was “no guarantee that even these meagre rations can be supplied”.

French industry was in a woeful state, too: “The evil of unemployment—in Paris alone some 400,000 persons are unemployed—has been added to the hardships caused by the lack of heat, food and clothing in the industrial centres of France.” With that came fears of political instability. We warned that there would be “a limit to French patience. And that limit is in sight…Faced with a growing volume of discontent, the government’s position might be weakened.” It was in everyone’s interest that “France should not become the neglected ally.”

Video: Getty Images

Britain and America, we argued, should treat France as an equal partner in the war effort, “not only in the formulation of strategy, but also in the allocation of resources”. America, with its abundant natural resources, could boost supplies to France. But Britain should also play its part—even if it “can contribute only pence to America’s pounds”.

Meanwhile a very different picture of liberation was emerging in eastern Europe, where the Nazis had been pushed out by the Soviet Union:

“A complete veil of secrecy has fallen over Russian-occupied Europe. Odd hints and pieces of information point to some political tension here and there, and to some extent armed clashes between Russians and local forces. But secrecy has made it almost impossible to gauge the scope and importance of these disturbances. Whatever its policy in the occupied territories, the Russian Government is not handicapped by the exacting demands of democratic opinion and parliamentary control.”

There did seem to be differences between the governments that formed under Soviet influence. In some countries the communists were in fact not intent on destroying all that remained of the old order. Bulgaria did not depose its king after the communists took power in September 1944; King Michael of Romania even received praise from the country’s communists, who wanted to show moderation (though both countries later became republics: Bulgaria in 1946, and Romania in 1947). In Poland, however, political divisions were much sharper. The Soviet-backed Lublin government wanted to abolish Poland’s 1935 constitution (they would eventually succeed), and fighting broke out between partisans and Russian soldiers.

What policy, we debated, would the Soviet Union choose to pursue in the territories it had helped liberate? On one hand, it might “decide to exercise control in such a manner that the national sovereignty of each small state is seriously impaired”. That would mean “ideological Gleichschaltung”—a term the Nazis used to describe taking total control of society. On the other hand, it might choose to exercise its influence in the region indirectly. In January 1945, it was hard to say which direction the Soviet Union would go in. ■

January 24

By late January, the Red Army was pushing through central Europe and advancing steadily towards Berlin, Germany’s capital. Ukraine, which the Nazis had seized in 1941 in order to control its wealth of natural resources, including wheat and iron ore, had been retaken by the Soviet Union in 1944. Meanwhile, in Poland, the Red Army had pushed into the cities of Warsaw and Krakow.

The German-controlled areas farther south were coming under attack, too. One such region was Upper Silesia, now situated mostly in southern Poland. An industrial heartland rich in coal and other commodities, it had become one of the main engines of Germany’s war economy (see the map below that we published in our January 27th issue). It was also the site of some of the Nazis’ largest forced-labour and concentration camps, including those that made up Auschwitz.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, parts of Upper Silesia had been held by imperial Germany, Austria-Hungary, Tsarist Russia, Poland and Czechoslovakia. These came under full German control after the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939. The region stretched across 8,000 square miles (21,000 square km) and was home to 4.5m people. “Within this region,” we wrote, “there are the richest coal deposits of the whole Continent”. Upper Silesia’s zinc deposits were also thought to be “the largest in the world”. The region’s coal made it vital for the production of chemicals, as well as electricity: “A dense gas and electricity grid, reaching as far as Breslau, depends on Upper Silesian coal.”

Upper Silesia was an industrial laggard compared with the Ruhr, a region in western Germany best known for producing coal and steel. Upper Silesia’s steel production was small by comparison, partly because it had too few local mines for iron ore. Yet this region had become central to the Nazi war machine, especially after the Allies began bombing the Ruhr heavily in 1943:

“It cannot be doubted, therefore, that during the last two years Upper Silesia has developed numerous new industries. Apart from new chemical plants, large factories for all kinds of war material have sprung up all over the area, usually being situated away from inhabited places and well camouflaged by forests and hills.”

After Allied bombing intensified, the Nazis relocated some of their heavy industry from the Ruhr to Upper Silesia. “There is no doubt,” we wrote, “that the most vital war factories have been built underground.” Everything from cement and fertiliser to trains and railway tracks were being produced there. By 1945, the railways of eastern Germany were dependent on the region’s coal. And so the loss of Upper Silesia, The Economist wrote, “would be a very severe blow to Germany’s war industry”.

It would also mean liberation for thousands of prisoners. On January 27th, the same day as The Economist’s article on Upper Silesia went to press, the Red Army seized control of Auschwitz from the Nazis. This was the Nazis’ biggest concentration camp; more than 1m Jews, Poles, Roma and others were killed there during the Holocaust. As the Red Army’s advance continued, the extent of the atrocities perpetrated by the Nazis in occupied Poland and elsewhere would become clearer still. ■

January 31

The second world war was tough on Britain’s firms. Many of the goods they had sold before the war were no longer being produced, as the country redirected resources to supporting the armed forces. Admen felt this keenly. “Brand goodwill,” wrote the Advertising Association in 1940, “is a capital asset of almost unlimited value: difficult to build; only too easy to lose.” “Let us guard our brand names during this economic upheaval,” it exhorted companies.

Not only did they have fewer products to hawk; they were also up against a vigorous campaign against profligacy. The Squander Bug, a cartoon menace dreamed up by the government who lured shoppers into wasting money rather than investing in war bonds, appeared repeatedly in propaganda. The bug was described as “Hitler’s pal”.

And yet, throughout the war, British brands managed to keep themselves at the front of consumers’ minds. Leafing through the ads we printed early in 1945 reveals a lot about life on the home front. The makers of Bovril, a meat-extract paste that can be brewed into a beefy drink, touted the “warmth and cheeriness” it could offer Britons in the dead of winter. Crookes, a drug company, marketed halibut oil as “an essential of wartime diet”, especially “during this sixth winter of war”.

Ads for the finer stuff appeared in our pages, too—with a twist. Whisky production had collapsed in the early 1940s, as grain supplies were funnelled towards food, before slowly starting up again in 1944. White Horse, a distiller, tried to capitalise on that shift by advertising its stock of “pre-war whisky”, which had been “growing old when this war was young”. An ad for Black Magic (a brand still sold today, now owned by Nestlé) promised that chocolates which had long been out of production would soon be back on sale: “Come Peace, come Black Magic.”

Other firms used their ads to demonstrate their role in the war effort. Daimler and Singer, two carmakers, sought to win over The Economist’s readers by showing off the kit they had provided to secure Britain’s power in the air, on land and by sea. Daimler built armoured vehicles for infantry; both firms made aircraft parts. Kodak, an American company, made cameras for Allied soldiers and bomber teams, who used them to record their position over an enemy target when a bomb was released.

Companies had used ad space in this way since the beginning of the war. But by January 1945, they were looking ahead to its end. Singer promised that the skill of its engineers, “heightened by five years’ devotion to the nation’s cause”, would “turn to the making of the future’s finest cars”. So did Lanchester, another carmaker. “The post-war Lanchester,” it promised, really would turn out to be a car “well worth waiting for”. ■

Keep reading

Images: Bridgeman; Getty Images

Video: Getty Images; The Economist

Source link