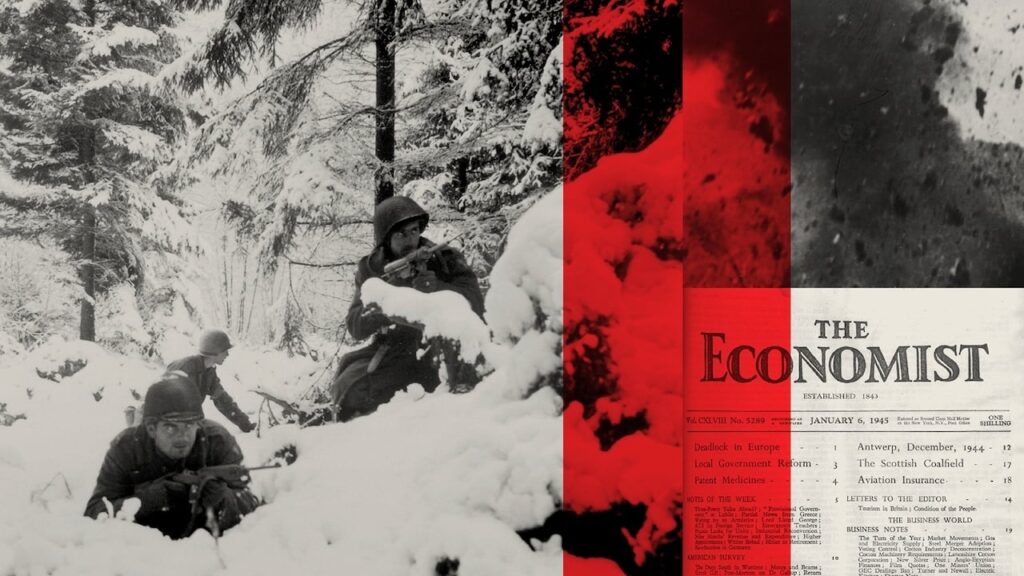

How The Economist reported on the final year of the second world war, week by week

In January 1945, 80 years ago, the second world war was entering its seventh year. Fighting raged in Europe, as Allied armies liberated large parts of France and Belgium from Nazi control. The Red Army was pushing from the Soviet Union into Poland, squeezing German forces from the east. Meanwhile the Allies’ campaign in the Pacific was gathering momentum, and America was planning for an invasion of Japan. The outcome of the war would transform the international balance of power, politics and the global economy in ways that still shape the world.

January 3

By January 6th 1945, when we published our first issue of the year, the conflict in Europe was in its last stages. We wrote that, late in 1944, “it was not only ordinary men and women who said, ‘It will all be over by Christmas.’” But the speed of the Allies’ advance into Nazi-occupied parts of Europe had slowed. Germany’s Rundstedt offensive (now better known as the Battle of the Bulge) had put the Allies on the back foot in Belgium and Luxembourg. The British were still fighting in Greece. Poland’s communists, known as the Lublin Committee, were at loggerheads with the Polish government-in-exile in London over who would control the country.

The mood in Britain was grim. Although the Nazis were still being squeezed on both sides of the continent, The Economist declared “Deadlock in Europe”:

“The year 1945 is opening gloomily for the Allies. Fighting still goes on in Athens. The Lublin Committee has added another twist to the tangled knot of Polish politics by declaring itself the provisional government of Poland. Across the Atlantic, American criticism of Britain and distrust of Russia show but little sign of abating. Militarily, too, the outlook is disappointing. The Rundstedt offensive has been checked, but that it should have succeeded at all grievously contradicts the high hopes of last summer.”

It was not that victory felt distant to Britons—in fact it looked all but assured. But “military deadlock and political disunity” had delayed the Nazis’ defeat. Disagreements over how Germany would be treated after the war were a problem. The Nazis, we wrote, were hoping “that the coalition against them will, after all, collapse”. And a proposal for post-war Germany to cede its industrial heartlands, advanced by France and the Soviet Union, was giving Germans a stronger will to fight on.

Britain had reason to feel glum beyond the battlefield, too. Running a war economy had taken a heavy toll on its people. The Economist had recently received one of the first big releases of statistical data since the beginning of the war (though we explained that “reasons of security still demand that some remain secret until the defeat of both Germany and Japan”). War had transformed the British economy. It wasn’t just that the government had hiked taxes to pay for the war effort. Spending on consumer goods had plummeted, even if fuel and light sold well during the Blitz—as we illustrated in this chart:

“No motor-cars, refrigerators, pianos, vacuum cleaners, tennis or golf balls have been produced since 1942, and only very few radios, bicycles, watches and fountain pens.”

Rumours had swirled in 1944 that Adolf Hitler had died, gone mad or been confined by Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS (the Nazis’ main paramilitary group). But Hitler’s New Year address, we wrote, showed that he was “alive, no more insane than usual, and not dramatically imprisoned”:

“His talk was full of the German myth, the rebuilding of bigger and better German towns, the failure of the bourgeois world and the new dawn of National Socialist principles…He appears to have passed beyond even a remote interference in the strategy of the war and to be now little beyond the focus for the despairing nationalism of the German people.”

Still, with the Nazis being pressed by the Allies in the west and the Soviet Union in the east, the dictator’s appeals to nationalism were ringing hollow. Rather, his message smacked of bluster and desperation. ■

January 10

While the Allies squeezed the Nazis in Europe, American forces in the Pacific put pressure on Japan. It had bombed Pearl Harbour, a naval base in Hawaii, on December 7th 1941, killing nearly 2,500 people. The next day President Franklin Roosevelt went to war in Asia. As 1945 began, America had checked the expansion of Japan’s empire and was making advances in the Philippines, which had been under Japanese occupation since 1941:

“The landing on Luzon, the largest of the Philippine Islands, has begun. Great American forces have already established four bridgeheads, and although tough fighting lies ahead, there can be no doubt that the last phase in the recapture of the Philippines has begun and that the end is in sight.”

The Economist turned next to China. America had been supporting it against Japan since 1940 with loans and weapons. In 1941 it sent military advisers and established air bases on the mainland. It had a strong interest in helping China end Japan’s occupation—not only to weaken Japan, but to strengthen China as a major power that would help enforce peace in Asia after the war.

This was no easy task. China was then run by a patchwork of rival governments. Outside the areas under Japan’s control, some of the country was led by the Kuomintang, a nationalist group led by Chiang Kai-shek, with a base in Chongqing, in central China; another area was controlled by the Communists, led by Mao Zedong, with a stronghold in Yan’an, a city in the north. Japan’s defeat could cause a situation “of the greatest confusion” in China, we wrote. Though the country’s two rival powers had fought alongside each other against the Japanese, they had also “been for some years in a state of actual or latent civil war”.

The civil wars that had broken out in liberated countries in Europe seemed to augur ill for China:

“In face of this situation—a potential Greece of the Far East, on a vaster and even more damaging scale—what policy ought the allies to pursue? China’s allies suffer from this grave disadvantage, that foreign intervention is always unpopular, and interference, if pressed too far, may end in nothing but violent dislike for those who have done the interfering…It is therefore with the utmost patience and tact that the Allies must press on both sides in China the need for unity.”

But unity, we noted, would be hard. Chiang seemed motivated “more by the desire to maintain and reinforce power than by any wish to share power in some new administration with the Communists”. The Communists were determined “to maintain power in their own areas and spread it where they can”. Though we argued that a government of national unity would be best for China, it was hard to see how it was to be “brought into being”. ■

January 17

By the beginning of 1945 most of France had been liberated. The previous August, the Allies had wrested Paris from German control and Charles de Gaulle, who had led a provisional government in exile from London and Algiers, returned to the capital. Occupation had taken its toll. On January 20th 1945, The Economist wrote:

“France has been allowed to drift into a position from which it must be speedily rescued. The population of Paris and of many other towns is shivering from lack of coal; during the first week of this month daily deliveries to Paris averaged little more than 10,000 metric tons, a mere fraction of normal requirements and barely enough to meet the urgent need of hospitals, schools and essential public services.”

Bread was rationed at 13 ounces (370g) a day, and cheese at 0.75 ounces (20g) a week. Even then, there was “no guarantee that even these meagre rations can be supplied”.

French industry was in a woeful state, too: “The evil of unemployment—in Paris alone some 400,000 persons are unemployed—has been added to the hardships caused by the lack of heat, food and clothing in the industrial centres of France.” With that came fears of political instability. We warned that there would be “a limit to French patience. And that limit is in sight…Faced with a growing volume of discontent, the government’s position might be weakened.” It was in everyone’s interest that “France should not become the neglected ally.”

Video: Getty Images

Britain and America, we argued, should treat France as an equal partner in the war effort, “not only in the formulation of strategy, but also in the allocation of resources”. America, with its abundant natural resources, could boost supplies to France. But Britain should also play its part—even if it “can contribute only pence to America’s pounds”.

Meanwhile a very different picture of liberation was emerging in eastern Europe, where the Nazis had been pushed out by the Soviet Union:

“A complete veil of secrecy has fallen over Russian-occupied Europe. Odd hints and pieces of information point to some political tension here and there, and to some extent armed clashes between Russians and local forces. But secrecy has made it almost impossible to gauge the scope and importance of these disturbances. Whatever its policy in the occupied territories, the Russian Government is not handicapped by the exacting demands of democratic opinion and parliamentary control.”

There did seem to be differences between the governments that formed under Soviet influence. In some countries the communists were in fact not intent on destroying all that remained of the old order. Bulgaria did not depose its king after the communists took power in September 1944; King Michael of Romania even received praise from the country’s communists, who wanted to show moderation (though both countries later became republics: Bulgaria in 1946, and Romania in 1947). In Poland, however, political divisions were much sharper. The Soviet-backed Lublin government wanted to abolish Poland’s 1935 constitution (they would eventually succeed), and fighting broke out between partisans and Russian soldiers.

What policy, we debated, would the Soviet Union choose to pursue in the territories it had helped liberate? On one hand, it might “decide to exercise control in such a manner that the national sovereignty of each small state is seriously impaired”. That would mean “ideological Gleichschaltung”—a term the Nazis used to describe taking total control of society. On the other hand, it might choose to exercise its influence in the region indirectly. In January 1945, it was hard to say which direction the Soviet Union would go in. ■

January 24

By late January, the Red Army was pushing through central Europe and advancing steadily towards Berlin, Germany’s capital. Ukraine, which the Nazis had seized in 1941 in order to control its wealth of natural resources, including wheat and iron ore, had been retaken by the Soviet Union in 1944. Meanwhile, in Poland, the Red Army had pushed into the cities of Warsaw and Krakow.

The German-controlled areas farther south were coming under attack, too. One such region was Upper Silesia, now situated mostly in southern Poland. An industrial heartland rich in coal and other commodities, it had become one of the main engines of Germany’s war economy (see the map below that we published in our January 27th issue). It was also the site of some of the Nazis’ largest forced-labour and concentration camps, including those that made up Auschwitz.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, parts of Upper Silesia had been held by imperial Germany, Austria-Hungary, Tsarist Russia, Poland and Czechoslovakia. These came under full German control after the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939. The region stretched across 8,000 square miles (21,000 square km) and was home to 4.5m people. “Within this region,” we wrote, “there are the richest coal deposits of the whole Continent”. Upper Silesia’s zinc deposits were also thought to be “the largest in the world”. The region’s coal made it vital for the production of chemicals, as well as electricity: “A dense gas and electricity grid, reaching as far as Breslau, depends on Upper Silesian coal.”

Upper Silesia was an industrial laggard compared with the Ruhr, a region in western Germany best known for producing coal and steel. Upper Silesia’s steel production was small by comparison, partly because it had too few local mines for iron ore. Yet this region had become central to the Nazi war machine, especially after the Allies began bombing the Ruhr heavily in 1943:

“It cannot be doubted, therefore, that during the last two years Upper Silesia has developed numerous new industries. Apart from new chemical plants, large factories for all kinds of war material have sprung up all over the area, usually being situated away from inhabited places and well camouflaged by forests and hills.”

After Allied bombing intensified, the Nazis relocated some of their heavy industry from the Ruhr to Upper Silesia. “There is no doubt,” we wrote, “that the most vital war factories have been built underground.” Everything from cement and fertiliser to trains and railway tracks were being produced there. By 1945, the railways of eastern Germany were dependent on the region’s coal. And so the loss of Upper Silesia, The Economist wrote, “would be a very severe blow to Germany’s war industry”.

It would also mean liberation for thousands of prisoners. On January 27th, the same day as The Economist’s article on Upper Silesia went to press, the Red Army seized control of Auschwitz from the Nazis. This was the Nazis’ biggest concentration camp; more than 1m Jews, Poles, Roma and others were killed there during the Holocaust. As the Red Army’s advance continued, the extent of the atrocities perpetrated by the Nazis in occupied Poland and elsewhere would become clearer still. ■

January 31

The second world war was tough on Britain’s firms. Many of the goods they had sold before the war were no longer being produced, as the country redirected resources to supporting the armed forces. Admen felt this keenly. “Brand goodwill,” wrote the Advertising Association in 1940, “is a capital asset of almost unlimited value: difficult to build; only too easy to lose.” “Let us guard our brand names during this economic upheaval,” it exhorted companies.

Not only did they have fewer products to hawk; they were also up against a vigorous campaign against profligacy. The Squander Bug, a cartoon menace dreamed up by the government who lured shoppers into wasting money rather than investing in war bonds, appeared repeatedly in propaganda. The bug was described as “Hitler’s pal”.

And yet, throughout the war, British brands managed to keep themselves at the front of consumers’ minds. Leafing through the ads we printed early in 1945 reveals a lot about life on the home front. The makers of Bovril, a meat-extract paste that can be brewed into a beefy drink, touted the “warmth and cheeriness” it could offer Britons in the dead of winter. Crookes, a drug company, marketed halibut oil as “an essential of wartime diet”, especially “during this sixth winter of war”.

Ads for the finer stuff appeared in our pages, too—with a twist. Whisky production had collapsed in the early 1940s, as grain supplies were funnelled towards food, before slowly starting up again in 1944. White Horse, a distiller, tried to capitalise on that shift by advertising its stock of “pre-war whisky”, which had been “growing old when this war was young”. An ad for Black Magic (a brand still sold today, now owned by Nestlé) promised that chocolates which had long been out of production would soon be back on sale: “Come Peace, come Black Magic.”

Other firms used their ads to demonstrate their role in the war effort. Daimler and Singer, two carmakers, sought to win over The Economist’s readers by showing off the kit they had provided to secure Britain’s power in the air, on land and by sea. Daimler built armoured vehicles for infantry; both firms made aircraft parts. Kodak, an American company, made cameras for Allied soldiers and bomber teams, who used them to record their position over an enemy target when a bomb was released.

Companies had used ad space in this way since the beginning of the war. But by January 1945, they were looking ahead to its end. Singer promised that the skill of its engineers, “heightened by five years’ devotion to the nation’s cause”, would “turn to the making of the future’s finest cars”. So did Lanchester, another carmaker. “The post-war Lanchester,” it promised, really would turn out to be a car “well worth waiting for”. ■

Your browser does not support this video.

February 7

Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt and Josef Stalin had last met in Tehran, Iran’s capital, in late 1943. There they had agreed that Britain and America would open a second front against the Nazis in western Europe while the Soviet Union attacked from the east. Now, with German defences crumbling, the leaders of Britain, America and the Soviet Union convened again—in Yalta, a resort town in Crimea. “The world’s triumvirate,” we wrote on February 3rd 1945, “will again meet face to face to determine the last stages of the war and the first steps of the peace.”

Held from February 4th to 11th, the Yalta conference sought to thrash out a plan for how the Allies would govern Europe after the Nazis’ defeat. In Tehran the three powers had settled on having “zones of influence”: Russia would dominate central and eastern Europe and the Balkans, and Britain and America would hold sway in the Mediterranean. But the agreement reached at Yalta, we reported after the conference’s end, revised those plans. The three instead committed themselves to “the right…to all peoples, to choose their own form of government”.

As the aggressor, Germany would be subject to occupation by the Allies in order to prevent the resurgence of Nazism and to ensure the country’s eventual transition to democracy. Control would be split four ways between the three powers and France (although the boundaries of these “zones of occupation” were not finalised: the front lines were still moving, in the east and the west, at the time of the Yalta conference). Germany would also be demilitarised:

“The destruction of German militarism and of the German General Staff appears for the first time beside the annihilation of Nazism. The punishment of war criminals is reaffirmed. For the first time it is officially suggested that the Germans can eventually win ‘a decent life…and a place in the comity of nations.’ The ambiguities concern the economic and territorial settlement.”

But much about the implementation of this plan remained fuzzy, beginning with the demand for Germany to demilitarise. “Interpreted harshly, this could mean the total destruction of German heavy industry,” we wrote. “Leniently understood, it could mean a measure of Allied supervision—admittedly difficult—over a functioning German industrial system.” It was also unclear whether a demand for the country to pay reparations could override “a minimum standard of life for the Germans”. We worried that the declaration could even be used by the occupying powers to justify subjecting Germans to forced labour as a form of restitution.

And so The Economist reserved judgment on what had been achieved at Yalta: “No verdict can be passed on the terms as they stand. The interpretation is all.” In the end, America and Britain, which favoured a more lenient policy, would come to blows with the Soviet Union over its heavy-handed expropriation of German factories, and its refusal to send food from the country’s east to its more populous west. Tensions over the handling of occupied Germany would go on to shape the early years of the cold war.

In the years after Yalta, the West would also end up sharply divided with the Soviet Union over how to treat eastern Europe. The declaration did not spell this out. The Allies agreed that Poland would “be reorganised on a broader democratic basis, with the inclusion of democratic leaders from Poland itself and from Poles abroad”. After years of war, that seemed a fair outcome for Poland—if only it could be realised:

“Everything turns on the interpretation given in practice to such terms as ‘democratic,’ ‘free and unfettered elections,’ ‘democratic and non-Nazi parties,’ ‘not compromised by collaboration with the enemy.’ If these words mean what they say, and what British and Americans understand them to mean, then clearly a great advance has been made. To this only the execution of these plans can give a final answer…There is, however, one sure test. If the governments established under the Crimea Declaration and the communities they administer show healthy signs of dispute, differences of opinion, and genuine independence of political approach, it will be safe to say ‘Amen’ to the present proposals.”

The Yalta declaration would miserably fail to meet The Economist’s test. Stalin did not keep his promise to allow free elections in central and eastern Europe; with the Red Army controlling much of the region, there was little America and Britain could do to force him. In Poland, even as the leaders met in Yalta, Soviet forces began to crush opposition to communist rule. ■

February 14

While Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin were huddled at Yalta, the Soviet Union’s offensive in eastern Europe was moving at breakneck speed. On January 12th the Red Army had begun its charge through Poland towards Germany. By the middle of February, the Allies had “reduced Germany to its heartland between the Rhine and the Oder”, two rivers in the west and east. Whereas the Nazis had been able to slow the Allies in the west, the Red Army was much harder to stop. We explained:

“First of all, the Russian armies are decidedly superior in numbers. Once the break-through was achieved, the speed of the advance was accelerated by the dense network of roads. The rivers, lakes and swamps, common to eastern Germany and western Poland, were therefore no obstacle. Under these conditions, a mere stabilisation of the fighting on a new front along the Oder line cannot be more than a temporary halt, if it can be achieved at all.”

In other words, ever more of Germany, we predicted, would soon succumb to Soviet occupation. The area that remained under Nazi control was still big, stretching from the north-west Balkans and northern Italy to Norway, where a collaborationist regime was still in power. But, crucially, the Soviet offensive had dealt a heavy blow to the supply chains that kept Germany fighting.

By mid-February the Red Army controlled nearly all of Upper Silesia, an industrial region that was critical for Germany’s supply of coal and metals. Over the previous few weeks that loss had hit the Nazis’ war industry, and especially their armament factories. “Compared with production in Great Britain and the United States,” we reported, “Germany’s present output seems small and totally inadequate for replacing the losses and for equipping huge armies.” That did not necessarily doom the Nazis; as we noted, Germany had never kept up with Britain and America in the number of bomber planes it could manufacture, for example. But now it was building hardly any ships, apart from submarines and small boats.

With the loss of Poland, the Nazis had also relinquished farmland that produced huge amounts of staple foods. Some supplies were abandoned during the retreat. “Large stocks of potatoes must have been left behind,” we wrote. Efficient distribution networks were “thrown out of gear” as German towns received “a sudden influx of evacuees” and railways became “overburdened with military transport”. As a result, rationing was tightened: “The food cards, originally issued for the eight weeks’ period from February 5th to April 1st, will have to last for nine weeks, which means a reduction [in rations] of roughly 10 per cent.”

Nazi propaganda was growing increasingly desperate. The Volkssturm, a militia formed by Hitler in late 1944 to mount a final defence of Germany, featured heavily in the regime’s messaging. But morale among the group’s 1m men was miserable. Poorly equipped and mostly untrained, few were moved by appeals to Nazi fanaticism. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, the German army was scrambling to regroup after being driven from France and Poland:

“Behind this propaganda, which has never before used so many superlatives in describing the plight of refugees and the danger to the Reich, the reorganisation of the armies is undoubtedly progressing. Political opposition from generals and other officers, which provided the danger-point last summer, seems to be absent; in fact, after the purge of last year, effective opposition hardly seems likely at the moment. So far, the Allies’ policy of unconditional surrender appears to have resulted in an ‘Unconditional Defence.’”

And “Unconditional Defence”, as The Economist put it, was enforced brutally by the Nazis. Germans who showed signs of defeatism were punished harshly; large numbers of deserters were shot. For many Germans, it had been clear for months that the war was lost. ■

February 21

In the Pacific, by mid-February, the tide was turning in favour of America. “Manila, capital of the Philippines, has fallen within four weeks of the first American landings on the Lingayen beaches,” we wrote on February 10th. Before long, America would defeat the remaining Japanese forces on the islands, which they had occupied since 1941. Admiral Chester Nimitz, who led the American fleet in the Pacific, planned to use Manila as the main base for further naval operations against Japan. “We shall continue to move in the direction of Japan,” he said, “and we are optimistic of our ability to do this.” And indeed, by February 24th, Japan was in disarray:

“These are black weeks for the leaders and people of Japan. The Philippines are all but lost. American forces are landing on Iwojima, only six hundred miles from the coasts of Japan. Tokyo and other towns have received the first of what promises to be a continuous series of bombing raids from over a thousand American aircraft. At the same time, the news from Europe—the Crimea Conference and the sweeping Russian advances into Germany—suggests that the Allies may soon be free to concentrate all their resources against Japan.”

The assault on Iwo Jima (pictured), a strategically vital island that America would use to support bombing raids on the Japanese mainland, was only the latest in a series of American advances. Over the past two and a half years, America’s victories in the Pacific had precipitated high political drama in Japan. In the summer of 1944 General Tojo Hideki had been forced to resign as prime minister, after a string of defeats. His successor, General Koiso Kuniaki, was also struggling to improve Japan’s military fortunes. Though the Japanese press had aired serious complaints about the poor quality of the country’s aircraft, Koiso had failed to boost its war machine (within weeks of Manila’s fall, he too would resign, as America invaded Okinawa in April 1945).

The loss of the Philippines had laid bare Japan’s weaknesses. We noted that industrial shortages (probably including rubber and oil from South-East Asia) had become a big problem. “It is easy to see,” we wrote, “that in this situation it would need a great deal of optimism in Japan to-day to feel that there is still any chance of victory.”

Would the country lay down its arms or choose to fight to the end, as Germany was doing? A comparison to Italy seemed apt. There, a strong monarchy and relatively weak popular support for fascism meant that Italy surrendered soon after it began suffering big military defeats: the newly installed prime minister, Pietro Badoglio, did so in September 1943. (The king, Victor Emmanuel, had arrested Benito Mussolini, the country’s fascist dictator who was Badoglio’s predecessor, earlier that year.) The same factors were present in Japan: with the emperor still in charge and no mass movement in support of fascism, Japan might similarly be expected to give up. To force the country to accept “a fight to the finish,” we reasoned, “probably needs the backing of a mass party which so far the extremists have failed to create.” But there was a hitch:

“There is thus a certain amount of evidence to support the view that as the prospects of defeat grow more certain, the chance will increase of a change of regime in Japan bringing in the Japanese Badoglio, ready not to negotiate but to accept unconditional surrender. But it would be very rash to dogmatise, and there are other factors and forces that tell a different story. The centre of extremism in Japan is the Army and at every decisive turn in Japanese policy since 1931 the military leaders have had most of their own way. It is also true that their own way has hitherto been crowned with quick success.”

Faced with the possibility of a full-blown American assault, it seemed possible that Japan’s army would try to radicalise the country’s young nationalists and purge the moderates that remained in the government and at the Emperor’s court. “On such a base,” The Economist feared, “they could, perhaps, emulate the Nazis and build a regime tough enough to fight to the bitter end.”

Whether they would succeed in convincing Japan was not clear; some moderates, we wrote, still seemed to have the upper hand. Still, the thought of “a fight to the finish on the soil of Japan itself” was a chilling prospect: after all, the battle for Iwo Jima remains one of the bloodiest ever fought by America’s marines. As they became bogged down in vicious fighting on the heavily fortified island, Iwo Jima would show how catastrophic a ground invasion of the Japanese mainland could be. ■

February 28

While some of the bloodiest battles between America and Japan in the Pacific were only just beginning, for Britons victory in Europe felt close enough that The Economist allowed itself to look ahead to the end of the war. Life would not return to normal quickly. Britain’s economy had been pummelled, forcing the government to keep some rationing in place until as late as 1954. But it was obvious that, once the fighting stopped, pent-up desire for rest and relaxation would be strong:

“No one now believes that the ‘last all clear’ will herald an immediate resumption of pre-war life with its abundance of good things. The continuance of rationing, with only gradual relaxation, is accepted as inevitable. Nonetheless, the armistice with Germany will release a flow of spending—however much discouraged officially—which will pour through every gap not closed by definite per caput rationing. The end of the war will break the mould in which the social conscience has been set for the last five years. Few will give a second thought to saving fuel or money, making do and mending, or taking journeys which on any definition are not ‘really necessary.’”

It seemed only natural that Britons would crave “the first holiday since the last days of peace”. The government had long urged them to spend “holidays at home”; now it was no longer discouraging them from relaxing outside it. “Reunited families, demobilised ex-servicemen on paid leave, workers on holidays with pay, newly married couples, families of children who have never seen the sea, and others who have forgone wartime holidays” were just some of the groups that we expected would soon flock to British resorts, including Margate, Brighton and Eastbourne.

Video: British Movietone/AP

But it wasn’t clear the seaside resorts would be up to it. After years of sitting closed for naval-security reasons, it was easy to imagine “endless queues for meals and beds”. In 1944, when some resorts re-opened, they struggled to cope even with smaller crowds:

“The catering industries’ need for Government assistance is a matter of urgency. The lifting last year of the defence area ban on travellers resulted in an influx of visitors to East and South-East coast resorts which they were ill-prepared to receive and with which the railways could not cope. This year the number of holiday-makers is likely to be considerably larger, in view of the mood engendered by the military situation. People are now prepared to permit themselves some relaxation of effort. If the Armistice should come before the main holiday season, the demand for holidays will be heightened. The immediate prospect is one of an acute shortage of holiday accommodation.”

There were a few ways in which the government might try to help, The Economist noted. Some had floated the idea of state-run holiday camps—though this, we wrote, “mercifully, would be destined for unpopularity”. Better options, we thought, would be for the government to open up old army camps and industrial workers’ hostels to big groups, and to offer special loans to businesses that wanted to cater to holidaymakers. After years of anxiety over the country’s supply of guns and butter, worrying about ice cream and parasols must have felt like a relief. ■

Your browser does not support this video.

March 7

In western Europe, the Allies had suffered a tough start to the year. After advancing through Nazi-occupied France for most of late 1944, the Americans and the British had got bogged down. In mid-December Gerd von Rundstedt, a German general, had launched a counter-offensive in the Ardennes, between Luxembourg and Belgium. But by February the Allies had routed Rundstedt, whose forces were running out of supplies; and by March they were again pushing into German-held territory from the west.

“At last the Allies stand upon the Rhine, and tomorrow they may be across it,” we wrote hopefully in our issue of March 10th. There was just one more big river for them to cross before they reached the German heartland:

“The first week of March saw battles on the Rhine and the Oder which opened the final chapter of the European war. The Allied armies in the west are reaching the Rhine on a long front, from Coblenz to the Dutch frontier. Rundstedt, hopelessly outfought, has not even been able to keep the big towns on the left bank of the Rhine as bridgeheads for the Wehrmacht…His real objective can only be to delay the establishment of Allied bridgeheads across the Rhine for as long as possible. Even some success in this would bring no real relief to Germany.”

Over to the east, the Red Army, commanded by Georgy Zhukov and Konstantin Rokossovsky, had made it north to the Polish coast and cut off German forces around the port-city of Danzig (now Gdansk). Like the Allies massed on the Rhine in the west, the Red Army now faced the task of crossing the lower parts of the Oder, which flows north through eastern Germany to the Baltic Sea. Soon the Red Army would launch an assault on Stettin (now Szczecin), a city at the river’s mouth. “The next few weeks”, we reported, “are thus certain to see the last two great battles for river crossings in the German war.”

Meanwhile, in the Pacific, America was intensifying its bombing campaign in Japan. America had been bombing the Japanese mainland since 1942, but stepped up its campaign in 1944—first using air bases on mainland China and later from Saipan, an island that it captured from Japan that summer. Early strikes were targeted at military and industrial sites. But after difficult weather conditions caused a series of raids to fail, American generals abandoned that strategy. In January, Curtis LeMay took charge of operations and ordered firebombing raids on the cities of mainland Japan.

Most structures in Japanese cities, built from wood and paper, stood no chance against the firebombings. On the night of March 9th LeMay launched a massive raid on Tokyo. Close to 300 B-29 bombers dropped white phosphorus and napalm on the city, where it had hardly rained in weeks. That caused a firestorm. More than 100,000 inhabitants were killed and around 40 square kilometres of the city were ravaged. It was the deadliest bombing raid of the entire second world war. As the fighting in Europe entered its final stretch, the conflict in the Pacific was entering its most violent. ■

March 14

In March 1945 the Nazis were being squeezed from both east and west by the Allies. They were also under growing pressure from the south. The Balkans had been under German occupation for nearly four years. But in 1944 the balance of power shifted. The Red Army pushed south into the Balkans that summer, after storming westwards across Ukraine. Once there it joined forces with resistance fighters led by Josip Broz, a Croat communist who went by the party name “Tito”. With most of the peninsula liberated by the beginning of 1945, Tito met British and Soviet brass to plan the next stages of the campaign. As we reported on March 10th:

“Towards the end of February, Field-Marshal Alexander visited Jugoslavia and conferred with General Tolbukhin, the Soviet Commander-in-Chief in the Balkans, and with Marshal Tito. Presumably, they discussed ways and means to complete the liberation of the Balkans. Nearly the whole South-East of Europe has now been freed, though scattered pockets of German resistance exist throughout Jugoslavia. The Wehrmacht, however, still holds the whole of Croatia as well as the area between Lake Balaton and the Danube in north-western Hungary. These two strongholds cover the approaches to Austria.”

The liberation of most of Yugoslavia—the state that covered much of the western Balkans—and all of Romania had given the Red Army a route through Hungary to Austria. It would lay siege to Vienna in early April. But as the war drew to a close, the Allies’ success in driving the Nazis out of the Balkans was overshadowed by the political, ethnic and territorial conflicts bubbling up within the region itself:

“The political situation in the Balkans and in the Danube Basin is far less satisfactory than the military position. Uneasiness and tension prevail throughout the area. The freed peoples are suffering under two old and familiar scourges: the violence of social and political conflicts and the intensity of an infinite number of nationalistic feuds. Both the internal upheavals and the national conflicts are in one way or another linked with the relations between the great Allied Powers. The old and familiar Balkan problems are reappearing in a form that is only partly new; and they threaten to create international trouble.”

The governments formed after the Nazis’ withdrawal had proven unstable. In Romania, King Michael’s efforts to keep a non-communist government together failed for the third time in March, when Petru Groza, the leader of the left-wing Ploughmen’s Union, formed a new administration—with Russian support. (Andrey Vyshinsky, a Russian diplomat in Bucharest, “may perhaps be regarded as its midwife”, we wrote.) In Yugoslavia Tito, who had just won the support of the Serbian Democratic Party, was struggling to balance his support among Croats, Slovenes and other ethnic groups. Greece, which had erupted in civil war shortly after liberation, had settled into a truce. But sharp divisions between monarchists, communists and moderate republicans meant peace was destined to be short-lived.

Conflicts threatened to break out across borders, too. “The nationalist moods in the Balkans have been reflected in the long list of territorial claims that have already been put on record by nearly all the Balkan governments,” we wrote. In Greece we noted that chauvinistic demonstrations for a “Greater Greece” were growing, with crowds chanting: “Occupy Bulgaria for 55 years” and “Sofia! Sofia!” At the same time, many Greeks feared that Turkey might try to claim some of the Dodecanese Islands close to its coast. Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Romania were considering territorial claims of their own, too.

The proliferation of disputes both internal and external was worrying:

“The disturbing feature of this typically Balkan turmoil is that the local leaders, generals and chieftains apparently hope that they may be able to exploit possible rivalries between the Great Allied Powers in order to further their own claims. Almost automatically a situation has arisen in which the Left, on the whole, looks for assistance to Russia and the Right places its hopes on the intervention of the Western Powers. Vague political calculations are based on the most grotesque assumptions…It is idle to deny that the policies of the Great Powers on the spot sometimes lend colour to such interpretations.”

Brutal punishments for members of collaborationist regimes, communist smears of Western sympathisers as “fascists” and the emerging cold-war divide between pro-Russian elements and British and American officials were creating a dark, paranoid atmosphere in the Balkans. “The local Governments, parties and factions ought to be told quite bluntly that their hopes of benefiting from inter-Allied rivalry are futile,” we urged. Although in Greece civil war would boil up again in 1946, the worst ethnic wars that we feared did not break out in the 1940s. But, as much of the Balkans slid behind the iron curtain, the peninsula would end up divided by the cold war instead. ■

March 21

“It is not easy”, The Economist wrote on March 24th, “to give a picture of the Russian economy in the fourth year of the Russo-German war.” Since the beginning of Operation Barbarossa in the summer of 1941, when the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union, the Kremlin had been forced into a desperate fight for survival. Some of the most violent fighting of the second world war took place on the eastern front: the Soviet Union lost more citizens than all the other Allies combined. Now Josef Stalin, the Soviet leader, faced the enormous task of rebuilding destroyed towns, cities and industries. With Soviet troops within striking distance of Berlin, we looked at the problems facing the Russian economy and its capacity to recover.

The western regions of the Soviet Union, which were the site of heavy fighting as they were liberated from Nazi control, had experienced untold destruction. We wrote:

“Behind the fighting lines of the Russian armies there lie vast expanses of ‘scorched earth.’ That the destruction wrought there has been on a stupendous scale is certain, although that scale varies from province to province and from town to town. A tentative official estimate puts the area of total destruction at 700 square miles. From scores of cities and towns in the Ukraine and White Russia come reports of life shattered to its very foundations. In many towns, out of thousands of houses only a few dozen or a few hundred were left standing after the Germans had been expelled.”

Big, industrial cities in eastern Ukraine had suffered some of the worst devastation. One-third of the buildings in Kharkiv had been completely destroyed; four-fifths of those that remained were in need of serious repair. The situation across the region was similar. “A high proportion of the urban and rural population”, we wrote, “has been forced back into quasi-troglodyte conditions.” Caves and mud huts had become ordinary dwellings. Mines that were flooded by the Nazis as they fled were still inundated with water; the Soviet authorities had been able to drain only 7.5% of those in the Donbas after they retook the territory.

The state of the economy varied across the vast sweep of the Soviet Union, however. We explained:

“But the story of destruction, which can be continued indefinitely, tells only half the tale. The other half, which is not less striking, has been told by the reports on the industrial development and expansion that have taken place in eastern Russia during the war, as the combined result of the transfer of plant from the west and of an intensive accumulation of capital on the spot. Recently published figures and statements suggest that the rate of development in the east has been so great that it has enabled Russia’s heavy industries to re-capture their pre-war levels of production, and even rise to above them.”

Industrial production in the east, especially in the region around the Ural mountains and in Central Asia, had boomed. Figures for the production of steel—a primary input for weapons, transport and agricultural equipment—gave a sense of Soviet industry’s stunning growth: around 30% more high-grade steel was being produced by 1944 than in 1940. Electricity generation had boomed, too. The Soviet Union’s ability to substitute lost capacity in areas under occupation by expanding industry in the east played a big role in helping it to defeat the Nazis:

“By hard labour and unparalleled sacrifices Russia has thus succeeded in winning the war, not only militarily on the battlefields, but also economically, in the factories and mines. In spite of the tremendous devastation in the western lands, it can now find the basis for post-war reconstruction in its newly-built factories in the east.”

Reconstruction in the liberated territories of the western Soviet Union would lead to a slight slowdown in production in the east. “Even now”, we wrote, “there are signs that the liberation of western industrial areas has already caused some relaxation in the war effort of the eastern provinces.” But the Soviet Union was determined to maintain its industrial growth, including by pressing Germany for reparations to help finance its reconstruction. Stalin was determined that the Soviet Union should assert itself as a global power. Keeping up its wartime economic expansion would be key to that objective. ■

Keep reading

Images: Alamy; Bridgeman; Getty Images

Video: Getty Images; The Economist

Source link