Caffeine can help some bacteria to keep antibiotics out of cells, potentially reducing the effectiveness of the drug’s therapeutic effects, new laboratory studies suggest.

However, experts have warned that it is not yet clear how this effect occurs in humans, so caffeine drinkers don’t need to panic yet.

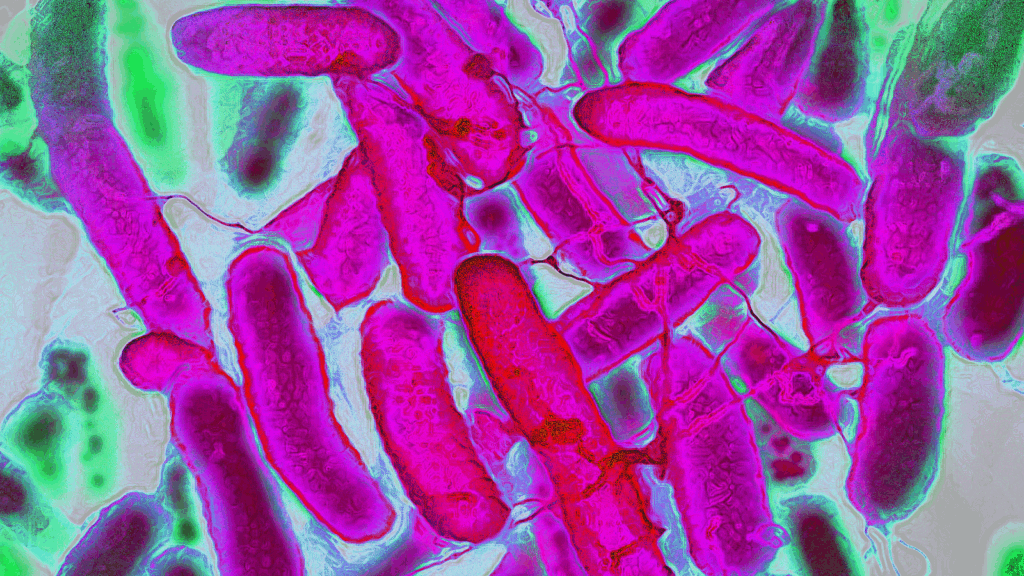

For decades, scientists have known that bacteria can protect themselves by pumping harmful substances through special transport proteins in the outer layer. This ability helps resist the effects of drugs that otherwise kill them. However, it was not clear how bacteria alter the activity of the genes behind these transport proteins in response to the molecules encountered.

You might like it

For more information, the researchers tested how the common gut bacteria E. coli, well known as E. coli, responded to 94 different compounds, including antibiotics and aspirin, and products made in the intestine, such as secondary bile acids. They also saw small molecules found in common foods, such as caffeine, which give vanilla its flavor.

Their study, published July 22 in the Journal Plos Biology, showed that many different chemicals can cause changes in bacterial transport-related genes and thus potentially affect the response to antibiotics.

Related: Super bugs are on the rise. How can I prevent antibiotics from becoming obsolete?

For example, caffeine has been found to reduce the production of a transport protein called OMPF, which helps bring common antibiotics, such as ciprofloxin and amoxicillin, to the membrane or internal organs of bacterial cells. In theory, due to the low availability of these OMPF proteins, antibiotics are not easily accessible to intracellular targets and are less effective.

However, this discovery should not be bothered by coffee drinkers. There are many potential variables that have not been studied yet, and Postdoctoral researcher at the University of Exeter was not involved in this study. “This includes whether the effects of caffeine reduce the body’s ability to remove infections,” Hayes told Live Science.

“Drinking coffee affects people’s reactions to antibiotics, and there is no evidence that no one should change their daily lives,” agreed Andrew Edwards, a professor of molecular microbiology at Imperial College, London. Edwards, who was not involved in the study, said he recommends that people who prescribed antibiotics follow doctor guidance and medication instructions.

Applicable microorganisms

In this study, researchers at the University of Tübingen in Germany looked at how seven genes involved in transport within E. coli reacted to different chemicals. Of the 94 substances they tested, 28 altered the activity of these genes.

The effective chemicals contained caffeine. Weed killer paraquat; certain classes of antibiotics, such as tetracyclines and macrolides. Salicylate, a broad class of drugs, including aspirin, also worked well.

“This study adds to the high level of gratitude that bacteria can sense and respond to many different stimuli, all of which can affect the susceptibility of microorganisms to antibiotics,” Edwards said.

A third of chemically induced genetic changes were involved in right audin-binding proteins (“rob” or “rob” for short), which switch genes on or off by binding to specific DNA sequences. Findings suggest that Rob plays a greater role in helping E. coli adapt to its environment than previously thought.

However, for now, it is still unclear how caffeine alters gene activity in E. coli, or how it interacts with ROBs at the molecular level. Furthermore, researchers still don’t know if the effects seen in lab experiments occur the same during actual infections.

In this study, the researchers discovered the ability of caffeine to interfere with how antibiotics also apply to E. coli strains sampled from real patients with urinary tract infections. This lab experiment suggests that the effects of caffeine on bacteria may have important implications for human health, but again, future research should confirm.

Future research will also be able to see microorganisms beyond E. coli. Researchers suspect their findings could also affect how other bacteria regulate transporters over time.

But what’s important is, “At this point, it seems very unlikely that caffeine consumption will lead to a difficult-to-treat infection,” Hayes said. “Overall, this study is interesting, but it is not a source of caffeine consumer concern.”

This article is for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide medical or nutritional advice.

Source link