Researchers at the University of Kiel, Dresden-Rossendorf Helmholtzzentrum and the University of Rostock are developing quantum simulations that can help predict the properties of warm dense matter and inertial fusion plasmas.

Nuclear fusion is the process of fusing two lighter atomic nuclei to create a heavier one, producing vast amounts of energy that power the heat and radiation of stars such as the Sun. For decades, scientists have been trying to achieve nuclear fusion in laboratories on Earth using a variety of concepts. In December 2022, a nuclear fusion experiment at the U.S. National Ignition Facility (NIF) achieved its first net energy gain¹, raising high hopes for addressing the dramatic increase in human energy consumption expected in the coming decades. Fusion provides a safe and clean energy source that complements solar and wind energy, and ambitious goals for fusion power plants have triggered significant government investment and private capital allocation in many countries in recent years.

Inertial confinement (or laser) fusion (ICF), which was used at NIF, promotes fusion by compressing a mixture of deuterium and tritium to enormous pressures (more than 100 times the density of a solid) with a high-power laser. The fuel starts as a cryogenic solid, turns into a liquid, then a gas, and then reaches a hot, dense plasma state where fusion reactions begin, rapidly producing large amounts of energy within a few picoseconds (millionths of a second).

Challenge to high-density quantum plasma and ICF simulation

Although theory and simulations of high-temperature plasmas have achieved a nearly comprehensive understanding of these systems, as they are relevant for explaining applications of magnetic fusion, for example, the situation is very different for inertially confined fusion plasmas. Here, reliable simulations must simultaneously consider numerous effects such as laser-matter interactions, shock propagation, and nuclear reactions. During the initial stages of the compression path, both the fusion fuel and the surrounding ablator must pass through the warm dense matter (WDM) region 2 in a controlled manner, i.e., without introducing strong inhomogeneities that cause instability. Although WDMs combine the well-known properties of the solid, liquid, and plasma phases of matter, but are not exactly equal to any of them, they are quite remarkable in their own right and occur naturally in a wide variety of celestial bodies, including the interiors of giant planets, the atmospheres of white dwarf stars, and the outer layers of neutron stars. From a theoretical perspective, its rigorous theoretical explanation is very difficult3,4. This is because it is necessary to comprehensively understand the complex interactions of effects such as Coulomb coupling between charged electrons and atomic nuclei, quantum delocalization and degeneracy effects, strong thermal excitations, and even partial ionization. Nevertheless, the pressing need to understand these extreme states of matter has driven the development of a variety of techniques (for a comprehensive overview, see Vorberger, J. et al.²):

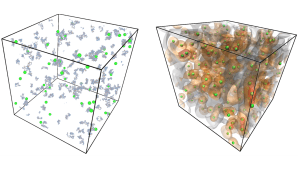

Chemical Models Radiation Fluid Dynamics Quantum Fluid Dynamics Semiclassical and Wave Packet Molecular Dynamics (MD) Averaged Atomic Models Density Functional Theory MD (DFT-MD)3, see Figure 2 Time-dependent DFT Fixed Node Quantum Monte Carlo (RPIMC) Simulations

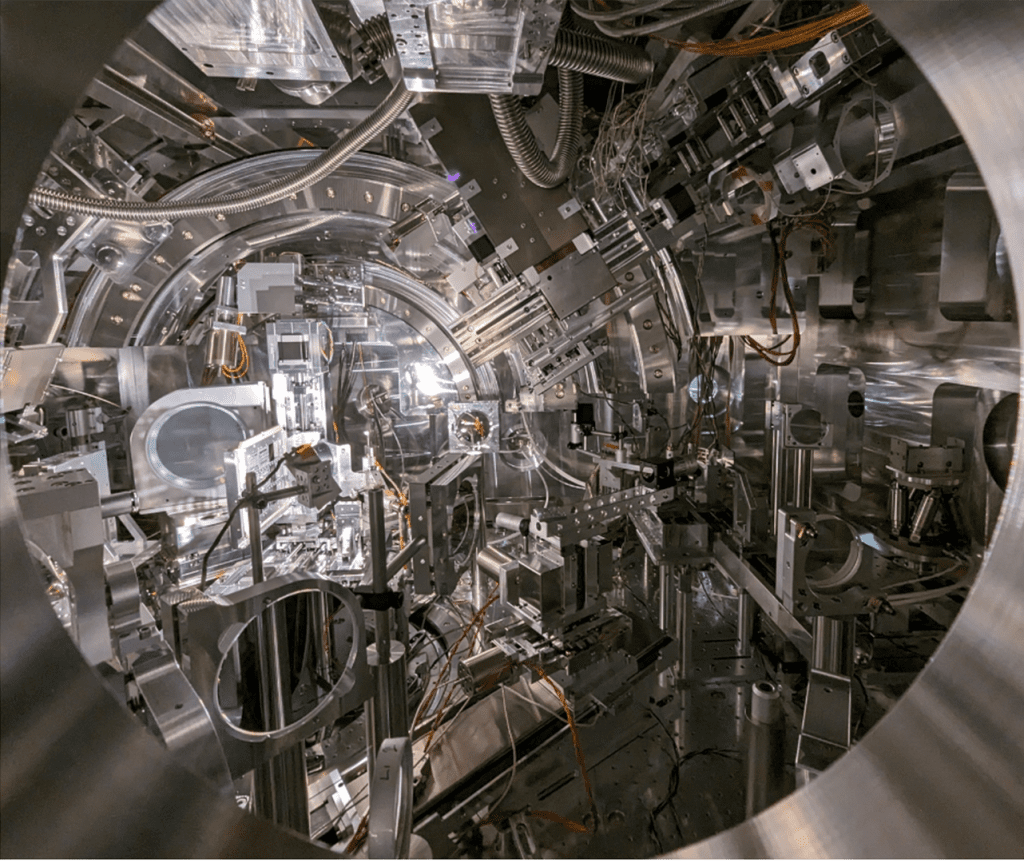

However, these simulations rely on various assumptions and approximations, which limit their predictive power. At the same time, experiments in creating and diagnosing WDMs are progressing dramatically in laboratories around the world (e.g., LCLS, NIF, Omega, Sandia Z machines in the United States, Laser Megajoule, European XFEL, GSI/FAIR in Europe, SACLA, Shengguang-II in East Asia), which requires accurate theory and simulation. An important example is the High Energy Density (HED) instrument at the European XFEL in Schönefeld, Germany (arguably the most advanced X-ray source in the world). Here, extreme states of matter can be generated using two state-of-the-art optical laser systems (DiPOLE and ReLaX) operated by the Helmholtz International Extreme Field Beamline (HIBEF, see Figure 1). Combined with XFEL, this setup enables repeatable pump-and-probe experiments to facilitate measurements and diagnostics with unprecedented precision, providing unique insights into the behavior of warm dense materials and beyond. The high level of precision that can be achieved by averaging potentially thousands of shots in sequence places equally strong demands on the corresponding theoretical description, which has given rise to new developments in first-principles simulations (simulations based directly on the fundamental equations of quantum theory) and new model-free methodologies for interpreting experiments.

Recent advances in first-principles simulation

The paucity of reliable theoretical results for warm, dense quantum plasmas has changed dramatically with important advances in first-principles simulations achieved by the authors and their collaborators. 2,6 Specifically, the list of ab initio methods includes:

Fermion Path Integral Monte Carlo Simulations for Thermodynamic and Spectral Properties⁷ (FPIMC, see Figure 2) Constructive Path Integral Monte Carlo (CPIMC) Implementation of advanced (semilocal and hybrid) explicit heat exchange correlation functions for DFT⁸ Implementation of high temperature and stochastic DFT methods⁹ Improved quantum equations of motion 10

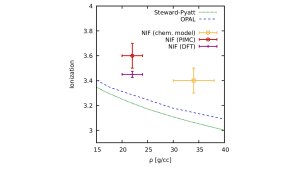

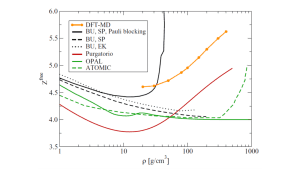

As a good example of the impact of these developments, we mention recent X-ray scattering experiments with strongly compressed beryllium at NIF11. The original analysis based on a traditional chemical model yielded a mass density of ⍴=34±4 g/cc, whereas the new ab initio FPIMC and DFT-MD simulations independently and consistently yielded a significantly lower value of ⍴=22±2 g/cc. ⁷ See Figure 3. The virtuous cycle between cutting-edge experimentation and simulation serves as a strong driver for new developments in both. The tremendous value of ab initio calculations as a benchmark for other models is further illustrated in Figure 4. Here we show the degree of ionization of carbon, an important ablator material in ICF experiments, as a function of mass density in a high-temperature environment.⁸ Clearly, existing models and data tables diverge towards strong compression, and reliable DFT/PIMC results are not required to establish a suitable baseline.

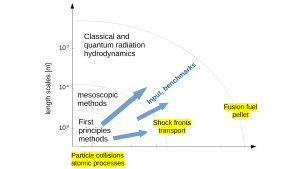

At the same time, it is important to recognize important limitations that remain. These new high-precision methods are computationally very expensive and are therefore limited to short lengths and short time scales. Therefore, the state-of-the-art results in limit-state nanophysics of WDM and related materials are not sufficient to comprehensively explain the complete temporal and spatial evolution of ICF experiments. In contrast, some of the simpler and less computationally expensive methods listed above are amenable to experimental scale, but lack the necessary reliability and precision.

Beskenhagen et al., Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023260 (2020)⁸.

Proposed solution (Figure 5)

A possible solution to this challenge can be obtained by intelligently combining a variety of different simulations, as first proposed in ⁶ and as we are further developing. The starting point is given by equilibrium quantum Monte Carlo simulations, which are the most accurate method available. It can be used as an impregnable benchmark and can be used to improve other first-principles methods, especially density functional theory. The latter is the most successful approach for large-scale calculations of rich material properties such as equation of state, thermal conductivity, and opacity. These characteristics are entered as input for a simpler method (see Figure 5), leading to improved descriptions of ICF applications on relevant time and length scales. On the other hand, in the simulation of nonequilibrium processes, the starting point role of first principles is taken over by nonequilibrium quantum kinetic theory⁹. This concept requires parallel development of each complementary simulation tool and should ultimately enable predictive ICF simulations in the near future.

References

Abu Shawareb, H. et al. (2024), Achieving greater-than-single target gain in inertial fusion experiments, Phys. Pastor Rhett. 132, 065102 Vorberger, J. et al. (2026), Roadmap for hot density matter physics, Plasma Physics. control. Fusion, arXiv:2505.02494 Graziani, F. et al. (Eds.) (2014), Frontiers and Challenges in Warm Dense Matter, Springer Bonitz, M. et al. (2020), First-principles simulations of warm dense matter, Phys. Plasmas 27, 042710 Dornheim, T. et al. (2022), Accurate temperature diagnosis of materials under extreme conditions, Nature Commun. 13, 7911 Bonitz, M. et al. (2024), First-principles simulations of dense hydrogen, Phys. Plasmas 31, 110501 Dornheim, T. et al. (2025), Elucidating electronic correlations in warm, dense quantum plasmas, Nature Commun. 16, 5103 Bethkenhagen, M. et al. (2020), Carbon ionization at gigabar pressure: an ab initio perspective on astrophysical dense plasmas, Phys. Rev. Res.², 023260 Fabian, MD et al. (2019), Stochastic density functional theory, WIREs Computational Molecular Science 9, e1412 Bonitz, M. (2016), Quantum Kinetic Theory, 2nd edition. Springer Döppner, T. et al. (2023), Observation of the onset of pressure-driven K-shell delocalization, Nature 618, 270-275.

Please note: This is a commercial profile

This article will also be published in the quarterly magazine issue 25.

Source link