China’s efforts to slow land degradation and climate change by planting trees and restoring grasslands are moving water around the country in huge and unexpected ways, a new study finds.

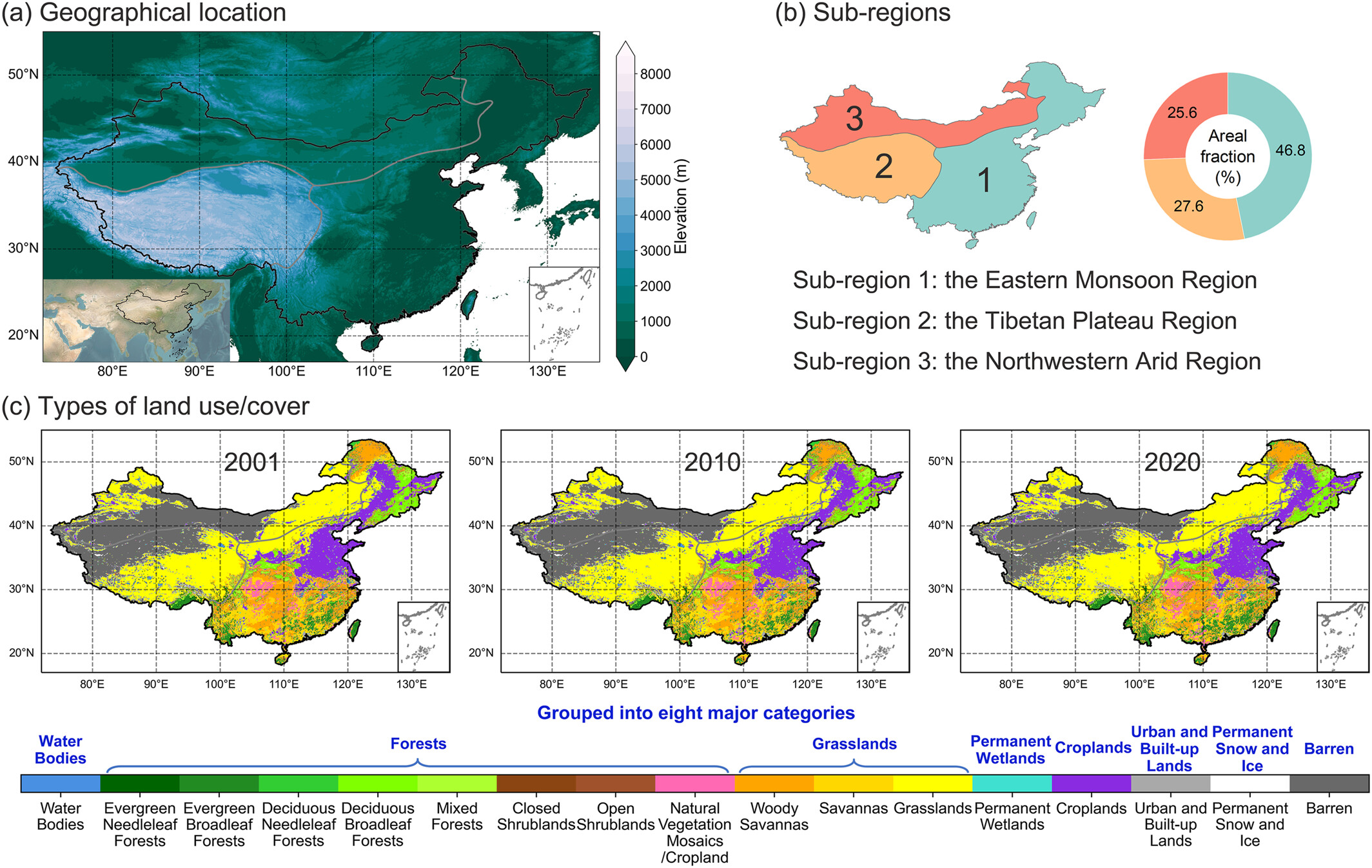

From 2001 to 2020, vegetation changes reduced the amount of freshwater available to humans and ecosystems in the eastern monsoon region and northwestern arid region, which account for 74% of China’s land area, according to a study published in the journal Earth’s Future on October 4. During the same period, scientists found that water availability increased in China’s Tibetan Plateau region, which makes up the remaining landmass.

you may like

There are three main processes that move water between Earth’s continents and atmosphere. Evaporation and transpiration bring water up, and precipitation brings water back down. Evaporation removes water from the surface and soil, and transpiration removes water absorbed by plants from the soil. Together, these processes are called evapotranspiration, which varies depending on plant cover, water availability and the amount of solar energy reaching the land, Stahl said.

“Both grasslands and forests generally tend to experience increased evapotranspiration,” he says. “This trend is particularly pronounced in forests, as trees can develop deep roots that access water in moments of dryness.”

China’s largest afforestation effort is on the Great Wall of China, in the arid and semi-arid regions of the country’s north. The Great Wall of China, begun in 1978, was built to slow the expansion of the desert. Over the past 50 years, forest area has expanded from about 10% of China’s area in 1949 to more than 25% today, an area comparable to Algeria. Last year, government representatives announced that they had completed vegetating the country’s largest desert, but would continue planting trees to prevent desertification.

Other large-scale greening projects in China include the Grain for Green Program and the Natural Forest Protection Program, both launched in 1999. The Grain for Green Program encourages farmers to convert farmland into forests and grasslands, while the Natural Forest Protection Program prohibits the logging of old-growth forests and encourages afforestation.

In total, China’s ecosystem restoration efforts accounted for 25% of the world’s net increase in leaf area from 2000 to 2017.

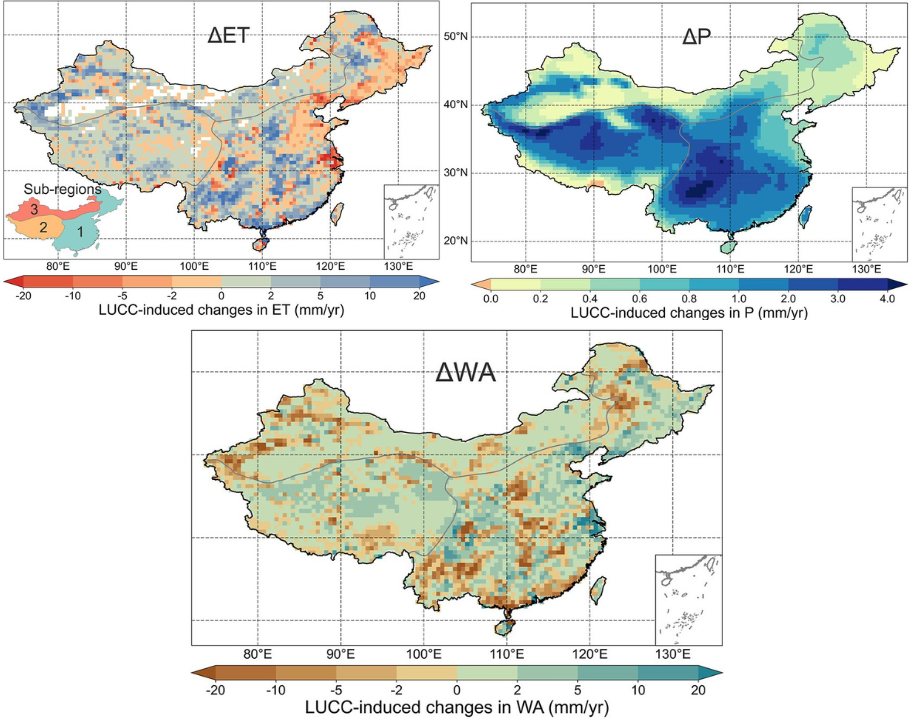

However, green regeneration has dramatically changed China’s water cycle, increasing both evapotranspiration and precipitation. To investigate these effects, the researchers used high-resolution evapotranspiration, precipitation, and land use change data from a variety of sources, as well as atmospheric moisture tracking models.

The results showed that evapotranspiration increased overall more than precipitation, which means some water is lost to the atmosphere, Stahl said. However, this trend was not consistent across China. Wind can carry water up to 4,350 miles (7,000 kilometers) from its source, meaning evapotranspiration in one place often affects precipitation elsewhere.

you may like

The researchers found that while forest expansion in China’s eastern monsoon region and grassland restoration in other regions increased evapotranspiration, precipitation increased only in the Tibetan Plateau region, thereby reducing water availability in other regions.

“Even though the water cycle is becoming more active, on a local scale we are losing more water than ever before,” Stahl said.

This has important implications for water management, as China’s water is already unevenly distributed. According to the study, the north has about 20% of the country’s water, but is home to 46% of the population and 60% of the arable land. The Chinese government is trying to address this. However, Stahl and colleagues argued that this measure is likely to fail if water redistribution through greening is not taken into account.

Ecosystem restoration and afforestation in other countries may also have an impact on the country’s water cycle. “From a water resources perspective, we need to consider on a case-by-case basis whether certain land cover changes are beneficial,” Stahl said. “It depends, among other things, on how much and where water that enters the atmosphere falls back down as precipitation.”

Source link