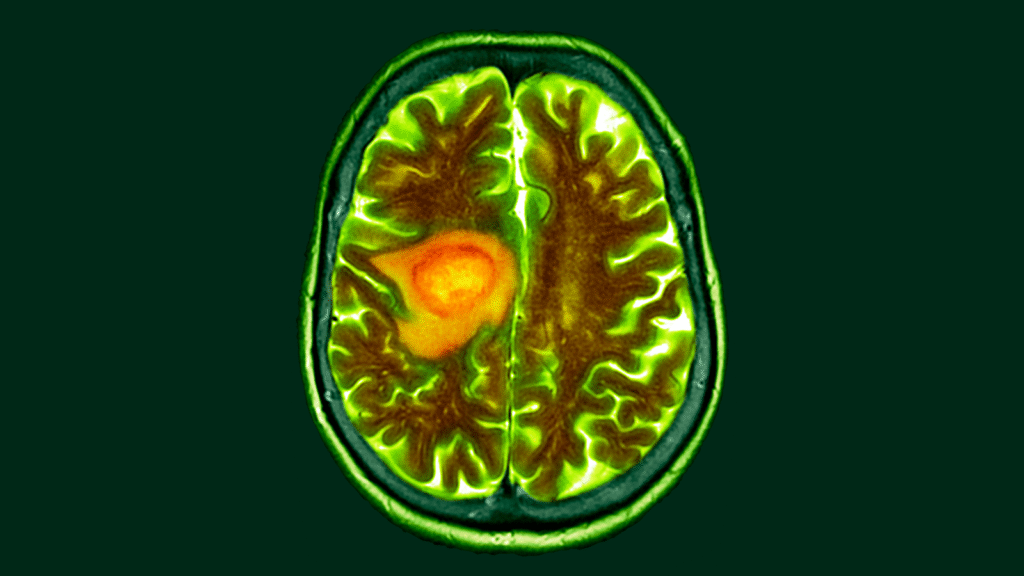

Dietary changes could make lethal brain cancer glioblastoma more vulnerable to cancer therapy, new research suggests.

Researchers behind the study believe that this dietary change exploits a key metabolic vulnerability in cancer, and their research shows that when used in combination with chemoradiation therapy, it expands survival in mice.

You might like it

Healthy cells in the brain require fuel to maintain an extensive list of functions such as electrical signaling and the release of chemical messengers. Research co-author Costas Lisiotis, a professor of oncology at the University of Michigan, disposes of these normal processes when rewiring to become “specialized split cells.”

These changes are of great interest to cancer researchers. This is because treatment may allow for the distinction between healthy cells and tumors and to make them more targeted.

“The real art of delivering therapy makes it so that you kill cancer rather than killing normal [cells]”Lyssiotis told Live Science.

Related: New treatments for most aggressive brain tumors may help patients live longer

The study, coordinated by Dr. Dan Waal, an oncologist at the University of Michigan, evaluated how glioblastoma distorts its metabolism in both human and animal brains. The study ambitiously combined laboratory research and clinical practice by drawing some of its data from tissues taken from the brains of patients undergoing cancer surgery. This study required collaboration with experts in brain surgery, metabolic pathways, and molecular analysis in humans and rodents.

The protocol began several hours before surgery. The patient received a glucose injection. This was tagged to be detectable by molecular analytical techniques. Glucose flowed through the bloodstream to both healthy and tumor cells.

A common approach to glioblastoma surgery is to remove the tumor and surrounding brain tissue to minimize the risk of cancer. The team took blood samples every 30 minutes during the surgery and flushed out tumors and healthy tissue that had been removed for analysis.

You might like it

These extracted cells metabolize glucose, and researchers tracked the molecular pathways through the cells. In collaboration with the mouse experiment, researchers gained a clear view of what tumor cells do differently when they engulf sugar.

Healthy cells metabolized glucose due to cellular processes such as respiration, where sugar and oxygen are converted to cellular fuel. These cells also converted glucose into an amino acid called serine, a key component of a critical neurotransmitter molecule.

In contrast, tumor cells put these processes aside. Instead, cancer cells directed glucose and produced nucleotides, or DNA components. These molecules are important fuel sources for the infinite replication of tumor cells.

Chemoradiation attacks cancer by destroying its DNA, but this rerouting gives cancer cells a stable source of nucleotides to repair damage. This study showed that tumor cells remove serine from surrounding tissues, further promoting their growth.

Here, Waal and his team saw the opportunity. They placed mice implanted with human cancer cells into feeding regimens that dramatically reduce dietary serine. Lyssiotis suggested that this could be replicated in human cancer patients with low protein diet supplemented with a serine-free protein shake.

This reduced the amount of serine available in tumor cells, which forced the cancer to return its glucose metabolism to serine production. This in turn reduces nucleotide synthesis and makes the cells more vulnerable to chemotherapy. Mice given this combination of treatments lived longer than mice receiving chemoradiation alone.

Lyssiotis explained that this vulnerability is likely to work for a limited period of time, as glioblastoma cells can skillfully adapt metabolism. Furthermore, some tumor cells appeared to be less dependent on the removed serine than other tumor cells. “If you can hit that sweet spot, you’ll take the serine, get treatment and get them before you understand the workaround,” he suggested.

Wahl has already begun work on follow-up clinical studies to back up these results in mice with data from human cancer patients.

“We hope to bring that to patients later this year or early next year,” he said. The task includes challenges and adjustments. “It’s difficult to get cancer treatment. We ask people to go out to radiation therapy every day and get chemotherapy. I think it’s difficult to ask them to follow the prescribed diet,” he added.

However, current research provides valuable information to inform future clinical research. “Part of what we’re excited about is that this isotopic tracing protocol is [tracking the tagged glucose] They can tell you which tumors produce serine from glucose and which tumors are taking serine from the environment,” says Wahl.

Lyssiotis noted that the paper’s pioneering metabolic analysis identified additional dietary changes that could be investigated in future work. Serine modifications are currently the easiest to implement. “I think that’s just the tip of the iceberg,” he said.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide medical or nutritional advice.

Source link