Approximately 40 million people worldwide are living with HIV. Advances in treatment have meant that infectious diseases are no longer the death sentence they once were, but researchers have so far been unable to find a cure. Instead, people living with HIV must take a cocktail of antiretroviral drugs for the rest of their lives.

But in 2025, researchers reported a breakthrough suggesting that a “functional” cure for HIV – a way to keep HIV under control for long periods of time without ongoing treatment – may actually be possible. In two independent trials using engineered antibody infusions, some participants remained healthy without taking antiretroviral drugs long after the intervention ended.

In one of the trials, the FRESH trial, led by virologist Thumb Ndungu of the University of KwaZulu-Natal and South Africa’s African Institute of Health Research, four out of 20 participants maintained undetectable levels of HIV for a median of 1.5 years without taking antiretroviral drugs. The other RIO trial, conducted in the UK and Denmark and led by Sarah Fiddler, a clinician and HIV research expert at Imperial College London, found that six of the 34 HIV-positive participants maintained viral control for at least two years.

you may like

These groundbreaking proof-of-concept trials show that we can harness the immune system to fight HIV. Researchers are now trying to run larger, more representative trials to see if the antibodies can be optimized to work in more people.

“I think there’s an opportunity for this kind of therapy to be a game-changer,” Fidler says. “That’s because they are long-acting drugs, meaning their effects can last long after they’re gone from the body.” “So far, I haven’t seen anything that works like that.”

People with HIV can live long, healthy lives if they take antiretroviral drugs. However, their lifespans are still generally shorter than those who have not been infected with the virus. And for many, daily pills, or more recently bimonthly injections, pose significant economic, practical and social challenges, including stigma. “For probably the last 15 or 20 years, there’s been a pragmatic effort to say, ‘How can we do it better?'” Fidler says.

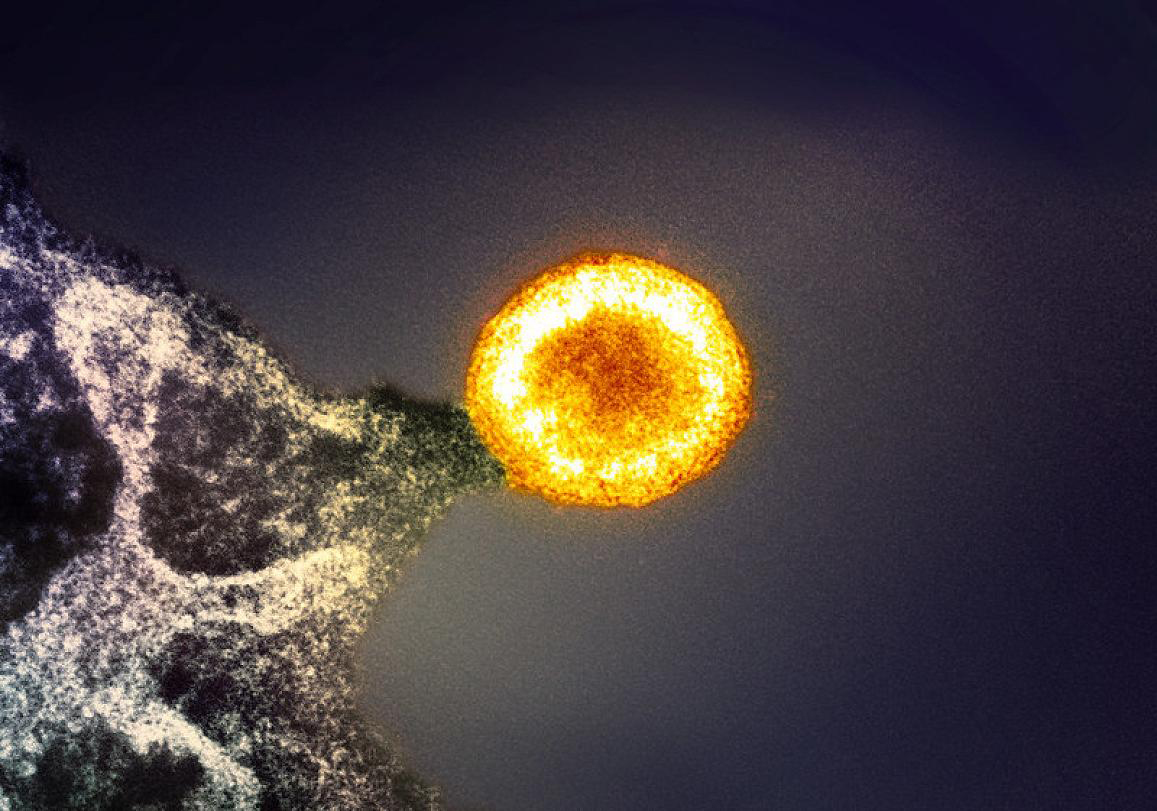

The dream, she said, is “to be cured of HIV, or what people call HIV remission.” However, this poses a major challenge because HIV is a master of disguise. The virus evolves rapidly after infection, so the body cannot produce new antibodies fast enough to recognize and neutralize it.

Additionally, some HIV is inactive and hidden inside cells, invisible to the immune system. These avoidance tactics have outwitted treatment attempts over the years. With the exception of a few exceptional stem cell transplants, interventions have not consistently resulted in a complete cure, or complete elimination of HIV from the body.

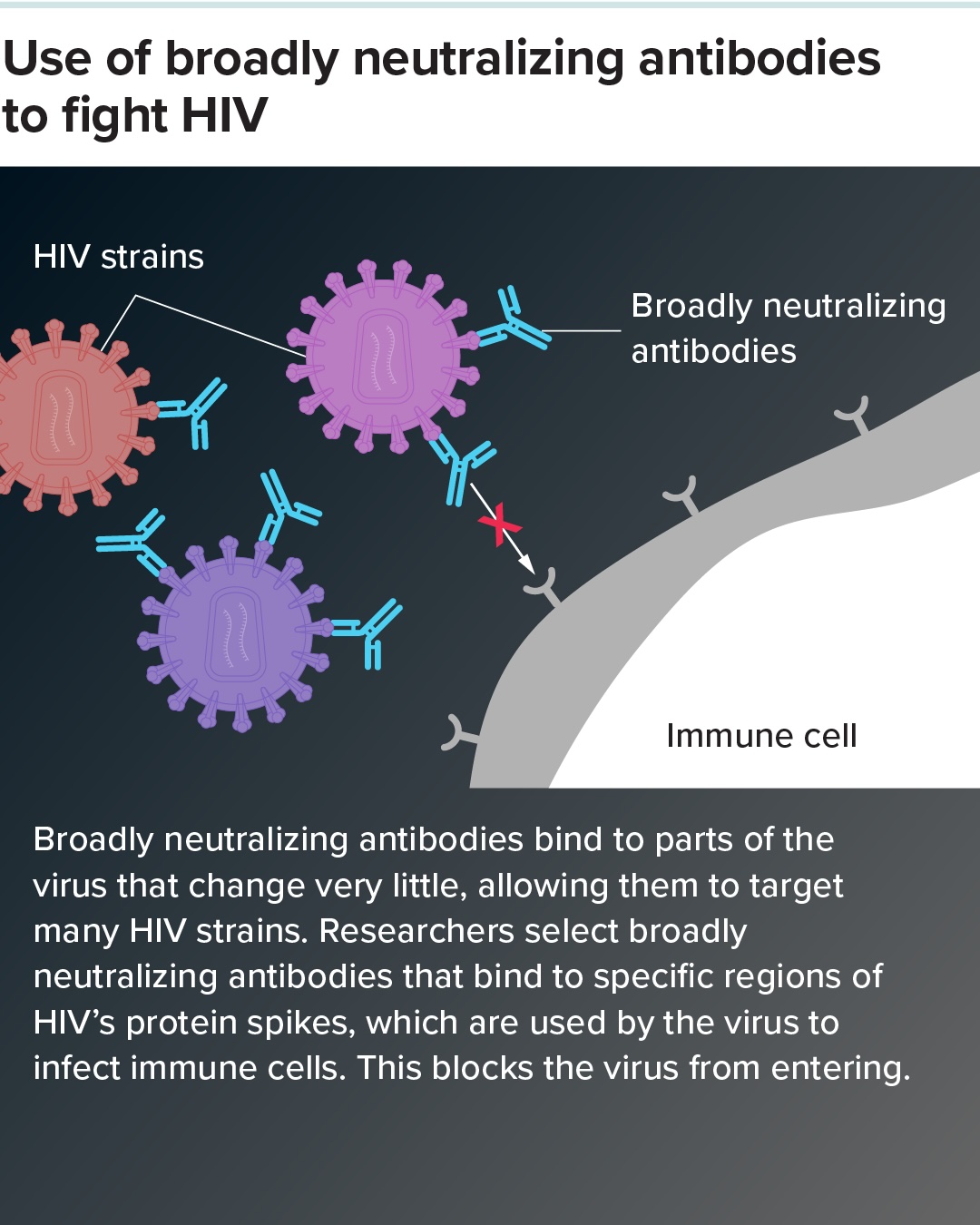

Functional treatment may be the next best option. And a rare phenomenon is bringing hope. Some people with long-term HIV infection develop antibodies that can eventually neutralize the virus, although it is too late to completely eliminate the virus. These powerful antibodies target important, rarely changing parts of HIV proteins in the outer membrane of the virus. These proteins are used by viruses to infect cells. Antibodies that can recognize a wide range of virus strains are called broadly neutralizing antibodies.

Scientists are currently racing to discover the most potent broadly neutralizing antibodies and engineer them into functional treatments. FRESH and RIO are perhaps the most promising efforts to date.

you may like

In the FRESH trial, scientists selected a combination of two antibodies likely to be effective against the strain of HIV known as HIV-1 clade C, which is predominant in sub-Saharan Africa. The trial enrolled young women from high-prevalence areas as part of a broader social empowerment program. Several years ago, the program started women on HIV treatment within three days of infection.

Meanwhile, the RIO trial selected two well-studied antibodies that have been shown to be broadly effective. The participants were primarily white men, around 40 years old, who were taking antiretroviral drugs soon after infection. Most are infected with HIV-1 clade B, which is more prevalent in Europe.

By combining the antibodies, the researchers aimed to reduce the chance that HIV would develop resistance, a common challenge with antibody treatments, since multiple mutations are required for the virus to evade both resistances.

Participants in both trials were injected with antibodies engineered to last in the body for about six months. Antiviral treatment was then suspended. The hope was that the antibodies would work with the immune system to kill active HIV particles and suppress the virus. If the effect is not sustained, HIV levels will rise after the antibodies break down, and participants will have to restart antiretroviral treatment.

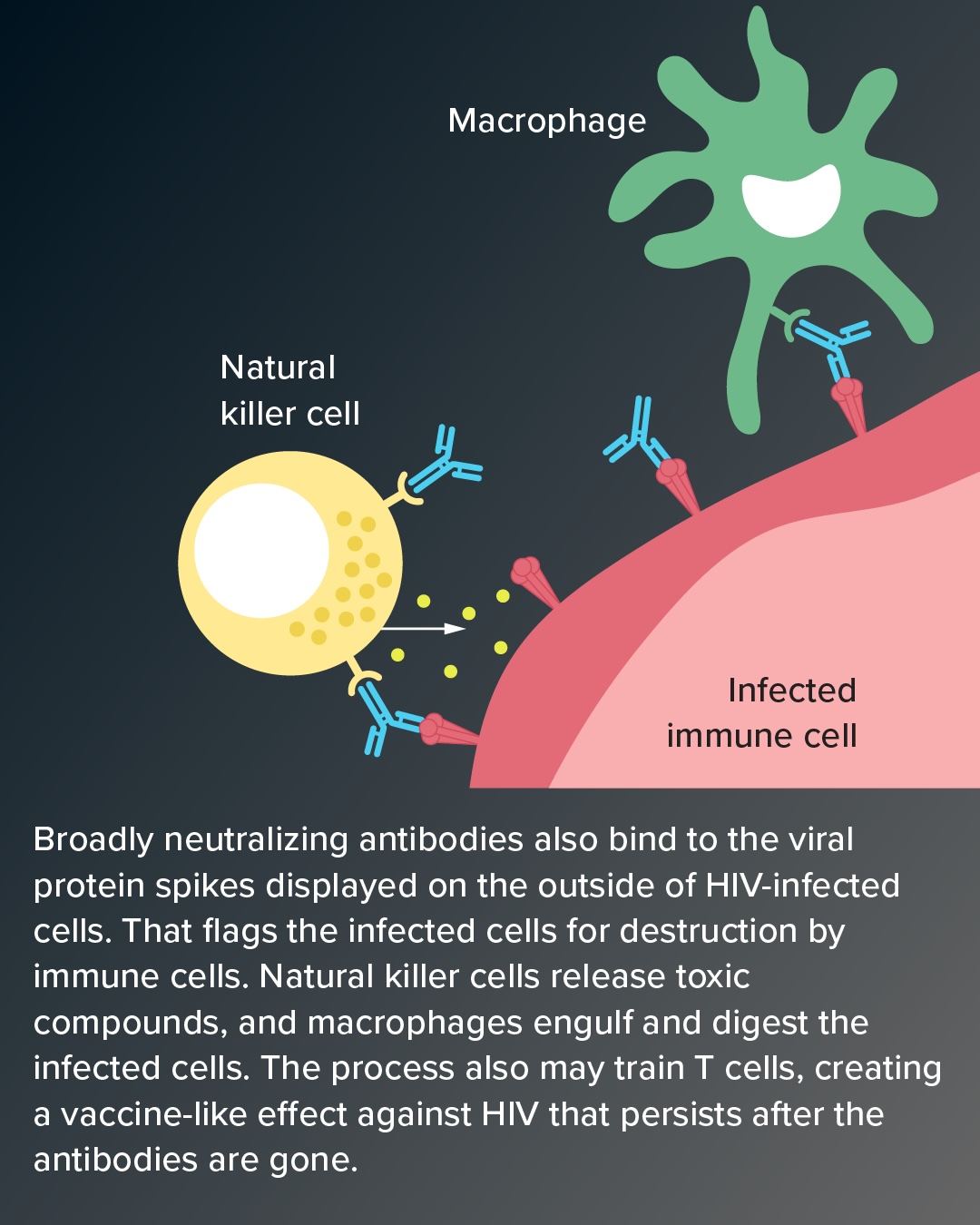

Interestingly, however, the results of both trials suggested that in some people the intervention stimulated an ongoing and independent immune response, which the researchers likened to the effect of a vaccine.

In the RIO trial, 22 of 34 people who received broadly neutralizing antibodies did not experience viral rebound by 20 weeks. At this point, they received another antibody injection. Even after 96 weeks, long after antibodies had worn off, the six people’s viral levels remained low enough that they did not need to take antiviral drugs.

An additional 34 participants included in the study as controls received saline infusions only, and most had to restart treatment in 4 to 6 weeks. All but three returned to treatment within 20 weeks.

A similar pattern was observed in FRESH (although, as it was primarily a safety study, this trial did not include control participants). Six of the 20 participants maintained viral suppression for 48 weeks after antibody infusion, and four of them remained untreated for more than a year. Two and a half years after intervention, one patient remained off antiretrovirals. Two others also maintained viral control but ultimately chose to return to treatment for personal and logistical reasons.

Researchers are cautious about calling participants in remission functionally cured because it is unclear when the virus will return. But the antibodies apparently pacify the immune system to fight the virus. When it attaches to infected cells, it signals immune cells to invade and kill them.

And importantly, researchers think this immune response to antibodies may stimulate immune cells called CD8+ T cells, which can hunt down HIV-infected cells. This may create an “immune memory” that helps the body control HIV even after antibodies run out.

This response is similar to the immune control found in a small proportion (less than 1%) of people infected with HIV, known as elite controllers. These people suppress HIV without the help of antiretroviral drugs, limiting it primarily to small reservoirs. Joel Blankson, an infectious disease expert at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and co-author of a paper on natural HIV regulators in the 2024 Annual Review of Immunology, says it’s interesting that the trial helped some participants do something similar. “It might tell us how to do this more effectively, and we might be able to put a higher proportion of people into remission.”

One thing scientists do know is that durable control is more likely to be achieved if antiretroviral treatment is started immediately after infection, when the immune system is still intact and the viral load is low.

However, post-treatment control can also occur in people who start taking antiretroviral drugs long after they were first infected, a group known as chronically infected patients. “It just happens less often,” Blankson said. “Therefore, the strategies included in these studies may also be applicable to patients with chronic infections.”

A particularly promising finding of the RIO trial was that the antibodies also affected dormant HIV hidden in some cells. These reservoirs are how the virus rebounds when people stop treatment, and antibodies aren’t expected to touch them. Researchers speculate that antibody-enriched T cells can recognize and kill latently infected cells that display trace amounts of HIV on their surface.

The FRESH intervention, on the other hand, targeted stubborn HIV carriers more directly by incorporating another drug called vesatolimod. It is designed to stimulate immune cells to respond to the HIV threat, potentially “shocking” dormant HIV particles from hidden locations. When that happens, the immune system can recognize and kill them with the help of antibodies.

The FRESH results are interesting, Ndungu said, “because they may indicate that the therapy was working to some extent. This was a small study, so obviously it’s difficult to draw very hard conclusions.” His team is still reviewing the data.

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge available to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.

Source link