Simple facts

Name: Hadrian’s Wall

What it is: a defensive wall built by the Romans who once guarded the northernmost frontier of the British empire.

How much is Hadrian’s Wall: 74 miles (118 km)

When was Hadrian’s Wall built: AD 122

Hadrian’s Wall served as the northernmost frontier of the Roman Empire for 300 years. The wall is located in the northern part of England and runs approximately 74 miles (118 km) between the boring Solway to the west and the east Wall Zend.

Construction began around 122 AD after a visit to England by Emperor Hadrian (ruled AD 117-138), who had decided to unite the borders of the Roman Empire. Britain and Wales fell into control of Rome by AD 61, defeated by Boudica, Queen of Aicuni. However, Scotland had successfully made Roman attempts to conquer thanks to people called the Caledonians, who thwarted attempts by the Roman legions to permanently rule the Scottish lowlands.

The wall was Hadrian’s attempt to establish a defensible border between the southern British and the unconquered north. Built using local materials by the Roman soldiers of II, VI and XX Legion, the first fortress of this wall ended within a few years, with mainly subsidized (non-Roman civil) units being placed.

You might like it

The wall would have made a strong impression on the locals, to say the least.

“We must imagine an area of the UK where there are not so many stone buildings and certainly not monumental masonry. It would have been completely alien,” said Miranda Aldhaus Green, professor emeritus in the Department of History at Cardiff University, in the 2006 BBC Timewatch Documentary. “It’s like a visit from another world, and people will be gobsmacked by it.”

How much is Hadrian’s wall?

Nic Fields, a researcher of ancient history, noted that when originally built, the eastern part of the wall was built of stone, running for 41 miles (65 km), ending at Newcastle upon Tyne. Eventually this expanded further east. We measured it about 10 feet (3 meters) wide and probably 15 feet (4.4 meters).

Meanwhile, the western part of the wall was made of grass, extended to 29 miles (47 km) and ended at Bounce-on-Solway. It was about 20 feet (5.9 m).

“Turf is a trial and tested building material, and its use in the western sector may indicate the need for speed of construction,” Fields wrote in his book Hadrian Wall AD 122-410 (Osprey Publishing, 2003).

To the north of Hadrian’s wall was a V-shaped groove, and to the south there was another line of defense known as “Valam,” which was gradually built. According to Rob Collins, an archaeologist at Newcastle University, who wrote “Hadrian’s Wall and the End of the Empire” (Routledge, 2012), Valm was “comprised of ditches lined with large earth walls or mounds.

Bones, a small gateway that can accommodate several soldiers, were placed every mile on the wall. Between each skeleton there were two turrets. Additionally, large fortresses were built around 7 miles (11 km).

These fortresses were up to nine acres (3.6 hectares) in size, shaped like a “trump” and had all the support facilities needed.

“Major buildings such as the Principia (headquarters building), Praetorium (commander’s house), and Horea (granny) were found in the central area. The area before and after includes barrack accommodation and other buildings,” Collins wrote.

Woman on Hadrian’s wall

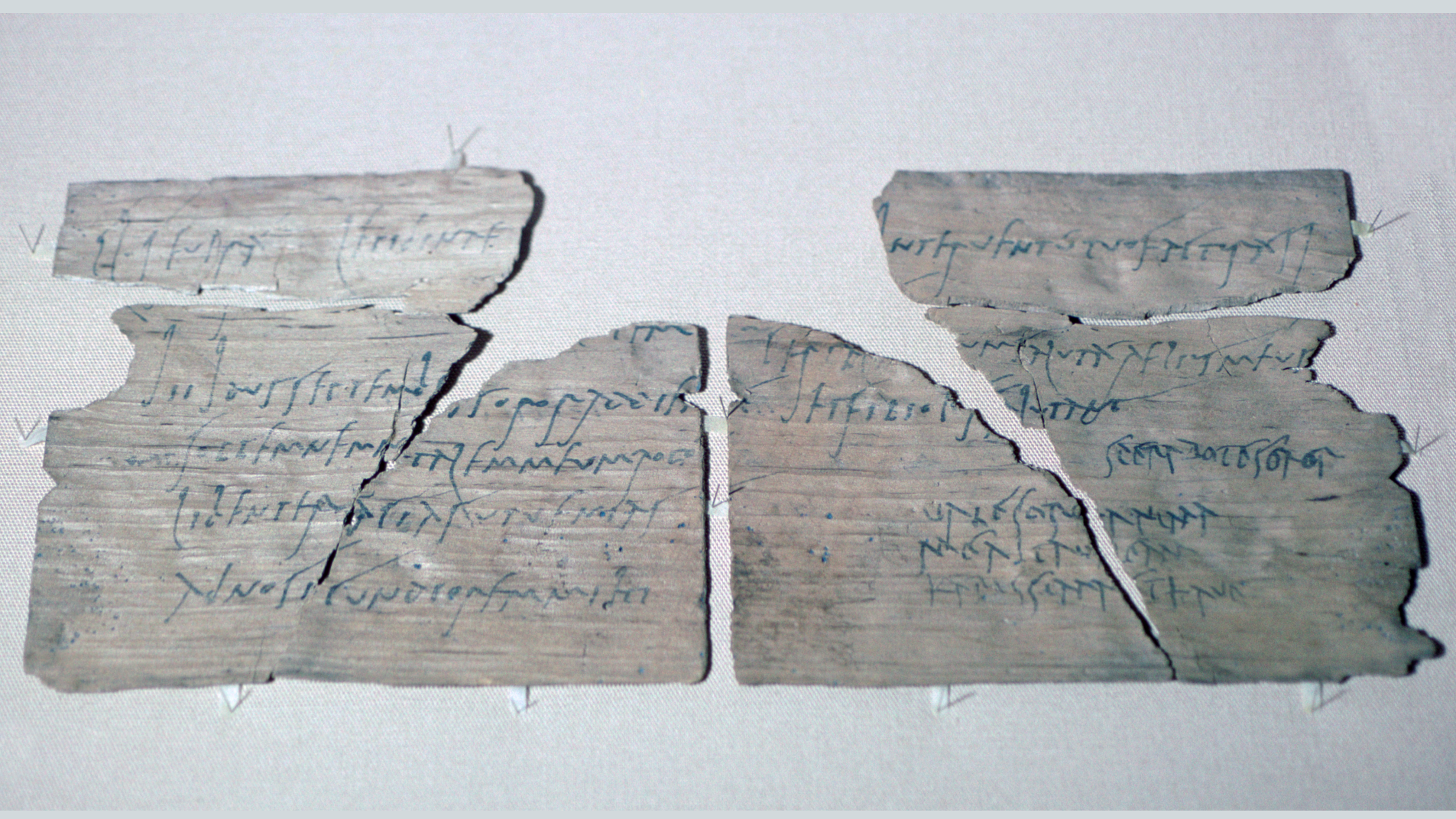

Hundreds of wooden tablets with handwritten Latin writing were excavated at Fort Vindolanda, giving us a glimpse into the daily lives of soldiers stationed there. This particular fortress was used before and after Hadrian’s wall.

The text reveals that senior military commander Vindlanda has a wife, and the tablet reveals a communication between the two women, Sulpicia Repidina and Claudia Severa. The two were isolated by their sexuality and social status, and they may have been lonely.

“The letters between them deal with small things such as invitations to come and visit. Claudia invites Sulpicia for her birthday,” wrote Geran Osborn in his book Hadrian Wall and His People (Liverpool University Press, 2006).

“I will give you a warm invitation to make sure you come to us. I will make the day more enjoyable for me by your arrival…” Read some of the invitations from Claudia (“Vindolanda Tablets Online”, translated from Oxford University).

The wife of a lower soldier in the fortress of Hadrian’s Wall had to be more careful.

“Lower men were forbidden from getting married. They have no connection to the area, so they can post quickly elsewhere,” Osborne wrote. “But whatever the ban is, ordinary soldiers contract illegal marriages and often protect their wives and children,” and “a civilian settlement adjacent to the fortress.”

Daily life at Hadrian’s wall

The same soil conditions in Vindolanda, which preserved the writing tablet, also preserved the leather products from the Roman era, providing new clues to the daily lives of soldiers and their families.

More than 7,000 preserved leather items have been discovered at Vindolanda so far, including tent panels, saddles and bags. Most of these leather items are shoes of all shapes and sizes that belong to men, women and children.

According to the project’s website, shoes are “particularly important for understanding military forts and settlements such as Vindlanda, as it has long been believed that only men live in military settlements.”

Excavations at another fort along the wall of Hadrian, known as Magna, produced some of the largest leather shoes ever seen at the Roman site. The eight XXL shoes correspond to men’s size 14 US (size 13 UK). The shoes may suggest that the Magna soldiers were very tall, but another interpretation is that they layered socks and sandals to avoid the cold, wet British weather.

Vindlanda also surprised archaeologists with a toy sword that is likely used by the soldiers’ children.

Over time the wall of Hadrian

When Rome’s military status in the UK changed, the walls changed too.

After Hadrian’s death at AD 138, his successor, Antoninus Pius (Governance AD 138-161), adopted a fundamentally different policy in the UK. He abandoned the Hadrian Wall and worked together to conquer the Scottish lowlands. After some success, he built a new fortress in Scotland, known as the Wall of Antonin.

Antoninus’ conquest was only proven temporary, and by the end of his reign the Scottish fortress had been abandoned, and Hadrian’s walls were taken away once more.

A series of modifications were then made to the wall. This includes replacing the grass section in favor of stone and building a road known as a “military road” south of the wall. Additionally, Collins noted that the turret appears to have been abolished and the bullet gateway appears to have been narrowed.

Over time, more changes have occurred. In the fourth century, the Roman Empire was subjected to greater military pressure, and Collins pointed out that the gates of the bullets were narrower and partially blocked.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 5th century and the beginning of the Dark Ages, the British political landscape changed, writing that the walls “have become politically redundant.” The fortress was quarried for stones, some of them were used to help build the medieval castles of England.

One particular location along Hadrian’s wall is the Sycamore Gap, a popular photo spot for decades. The large sycamore tree has grown next to the dramatic dip on the wall for over 150 years. In 2023, the tree was illegally cut down, and the person responsible was charged with criminal damage on the tree and the wall of Hadrian.

Editor’s Note: This work was originally published on November 1, 2012 and updated on August 4, 2025, and contains information on daily life in the Sycamore tree, which was illegally defeated in 2023.

Source link