Halley’s Comet is named after the famous astronomer who was the first to describe its movement through space, but new research suggests he wasn’t the first to discover its periodic orbit past Earth.

Halley’s Comet is named after the British astronomer Edmund Halley, who in 1705 pieced together the space rock’s orbit using a combination of his own observations and historical records from other observers. However, recent research suggests that Halley’s comet was not the first to discover the approximately 75-year cycle of his namesake comet. Instead, the English monk Aylmer of Malmesbury (also known as Ethelmer) may have linked the two observations of the comet more than 600 years ago.

you may like

In addition to his interest in flight, Aylmer also had a strong interest in astrology and astronomy. As a boy in 989, William of Malmesbury writes, he saw a comet hurtling over his home in England. Decades later, in 1066, he saw the comet again and linked the two events, argues Simon Portegis-Zwart, an astronomer at Leiden University in the Netherlands, in a new book.

Porgy’s Zwart, according to William of Malmesbury’s account, says that when Aylmer saw the comet in 1066, he exclaimed, “It’s come, hasn’t it?… It’s been a long time since I’ve seen you, but now I see you…” is even more frightening, because I see you brandishing the downfall of my country.” At the time, England was in the midst of a succession crisis, with no clear heir to the throne following the death of Edward the Confessor. If William’s records are accurate, Aylmer realized that the two “shining stars” he had seen were indeed the same. In any case, it is clear that William himself was aware of the connection.

Halley’s Comet was the first comet recognized by astronomers to appear periodically or repeatedly. It orbits the sun in a highly elliptical orbit. This elongated orbit causes it to pass close to Earth every 72 to 80 years, leaving a bright dust trail in its wake.

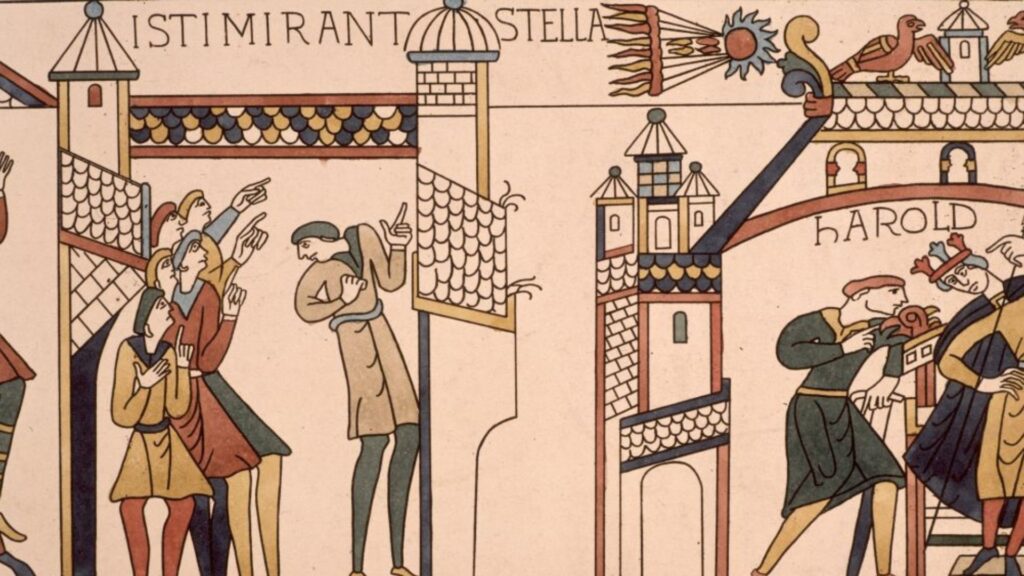

The earliest possible record of Halley’s Comet is in a Chinese chronicle from 239 BC. Since then, it has been recorded dozens of times by astronomers around the world, often interpreted as a kind of omen. For example, the Roman-Jewish historian Flavius Josephus believed that the sighting of a comet in 66 AD portended the fall of Jerusalem. The comet’s passage was sewn into the Bayeux Tapestry, which recorded William the Conqueror’s invasion of England in 1066, after it was seen flying over Brittany and the British Isles in April of the same year.

Astronomer Halley connected the comet’s appearances in 1531, 1607, and 1682. Halley went on to predict the comet’s return in 1758. Halley died in 1742 before seeing his prediction come true, but after his death, Halley was proven correct when the comet actually returned as predicted.

While Halley’s calculations were impressive, Porteghese-Zwart argues that Aylmer should be given credit for piecing together the appearance of comets centuries ago. He and Michael Lewis of the British Museum published a chapter discussing this point in their book Dorestad and Everything After: Ports, Townscapes and Travelers in Europe, 800-1100 (Sidestone Press, 2025).

The next pass in late July 2061 will allow you to catch Comet Halley (or Comet Aylmer). Mark your calendars now.

Source link