Milestone: ‘Town Child’ skull revealed

Date: December 23, 1924

Location: South Africa, Town

People: Raymond Dart’s Anthropology Team

In late 1924, anthropologists began chipping away at the rock around ancient primate skulls, rewriting the story of human evolution.

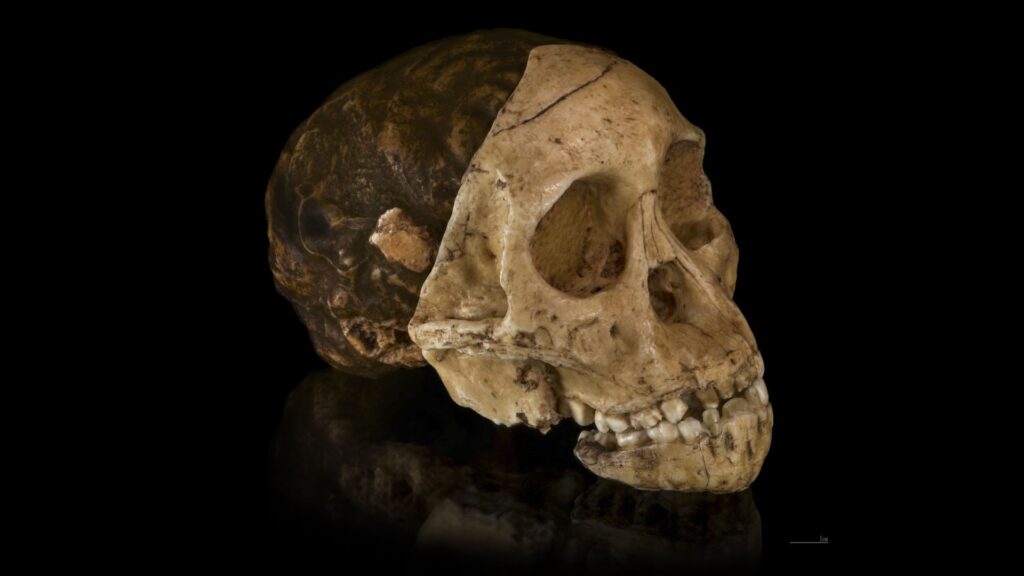

This tiny skull, about the size of a coffee mug, clearly belonged to a creature very different from us, and even different from other apes and monkeys.

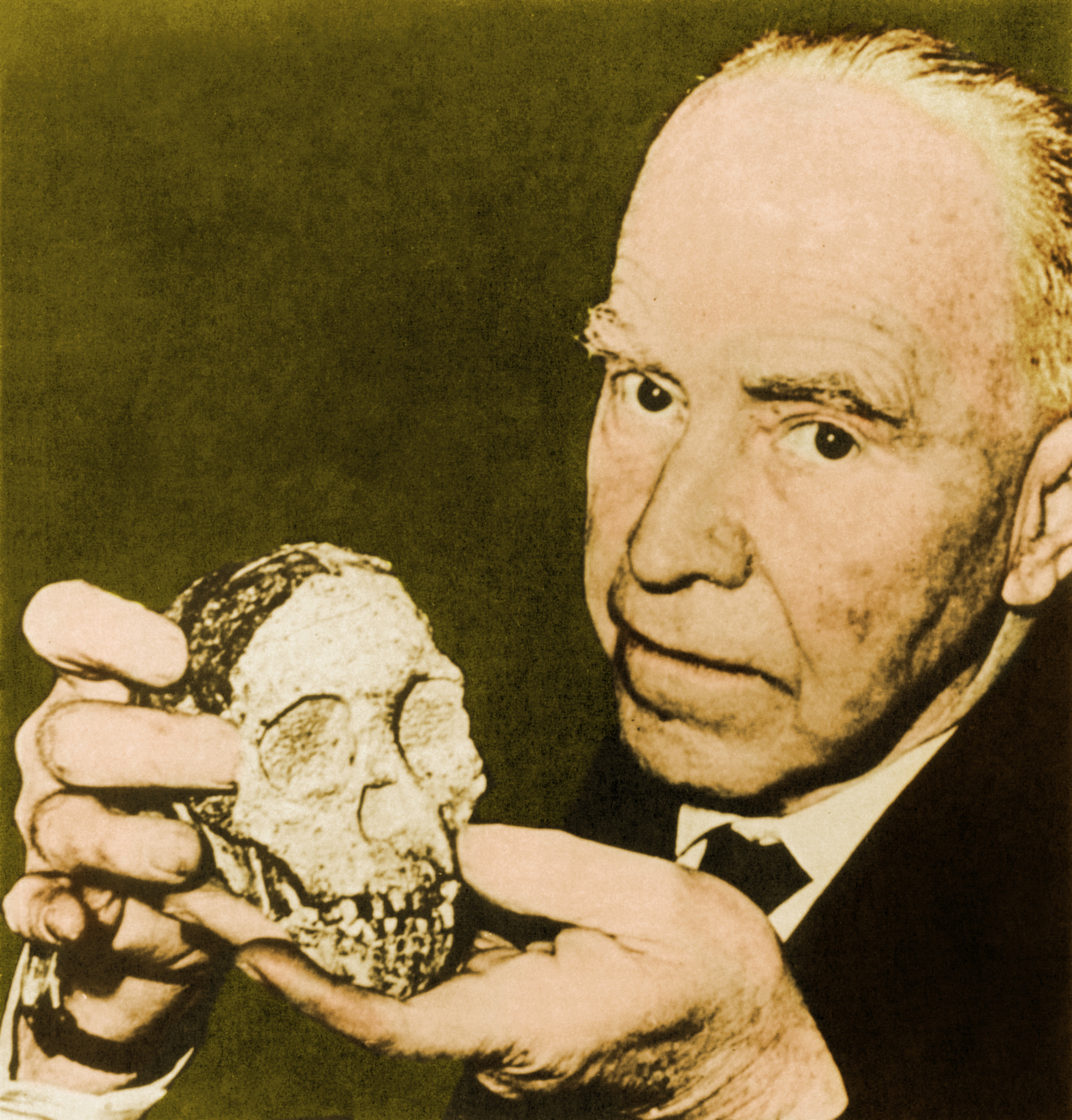

However, its discoverer, Raymond Dart, a professor of anatomy and anthropology at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, had never actually excavated the skull.

you may like

Rather, it was passed on to Dart because his student brought another skull from the quarry to class. Local workers at Buxton Limeworks in Town had previously knocked a baboon skull out of a rock and alerted the company. From there, the baboon skull landed with darts student Josephine Salmons. She recognized what it was and brought it to his class.

Excited by the possibility that other ancient primate fossils were buried in the same sediments, Dart showed the baboon skull to his geologist colleague Robert Young. Mr Young knew about the quarry and contacted the quarry’s Mr De Brian, asking him to keep an eye out for more skulls. In late November, De Bruyn discovered the brain embedded in a piece of stone and kept it for Young, who gave the skull to Dart.

In his 1959 memoir, The Missing Link, Dart does not mention that Young handed him the skull. Instead, he suggested the skull had been removed from a crate of rubble delivered from Buxton Limeworks.

According to Dart’s story, he immediately recognized what he had found.

“As soon as I removed the lid, a thrill of excitement ran through me. At the top of the pile of rocks was undoubtedly an intracranial mold or mold inside the skull,” Dart said in his memoirs. “I stood in the shade, cradling my brain as greedily as a miser cradles his money…I was convinced that here was one of the most important discoveries in human history.”

On December 23, “the rock split; the right side was still embedded, but I could see the face from the front,” Dart wrote in his 1959 memoir.

Over the next 40 days, he diligently analyzed the skull. In a paper published in the journal Nature on February 7, 1925, he described the newly discovered human ancestor and named it Australopithecus africanus, or “South African man-ape.”

you may like

“Town Child” catapulted Dart to fame and confirmed Charles Darwin’s theory that humans and non-human apes shared a common ancestor that evolved in Africa.

The discovery of Town Child was the first time scientists had discovered a nearly complete fossilized skull of an ancient human ancestor. The study found that the skull was longer than those of other primates, and that the skull’s molars suggested it was “anatomically equivalent to a six-year-old human child,” although subsequent estimates suggest that the child died around the age of three or four. Although no one knows for sure, most researchers believe Towne’s child was a girl.

Because the skull was removed from its “context,” it was difficult to determine its age. Over the years, some researchers have estimated that it is 3.7 million years old, but more recent research suggests that it is around 2.58 million years old.

For nearly 50 years, A. africanus was thought to be the direct ancestor of humans. Then, in 1974, scientists excavating in Afar, Ethiopia, unearthed another skull fossil of a closely related species. Dating back 3.2 million years, this is the iconic “Lucy” and her species, Australopithecus afarensis, would eventually unseat Town Child as our direct common ancestor.

However, there is a twist in this story, as scientists have discovered several fossil fragments that raise the possibility that Lucy’s species is not our direct ancestor after all, with some even suggesting that A. africanus may reclaim its title.

Source link