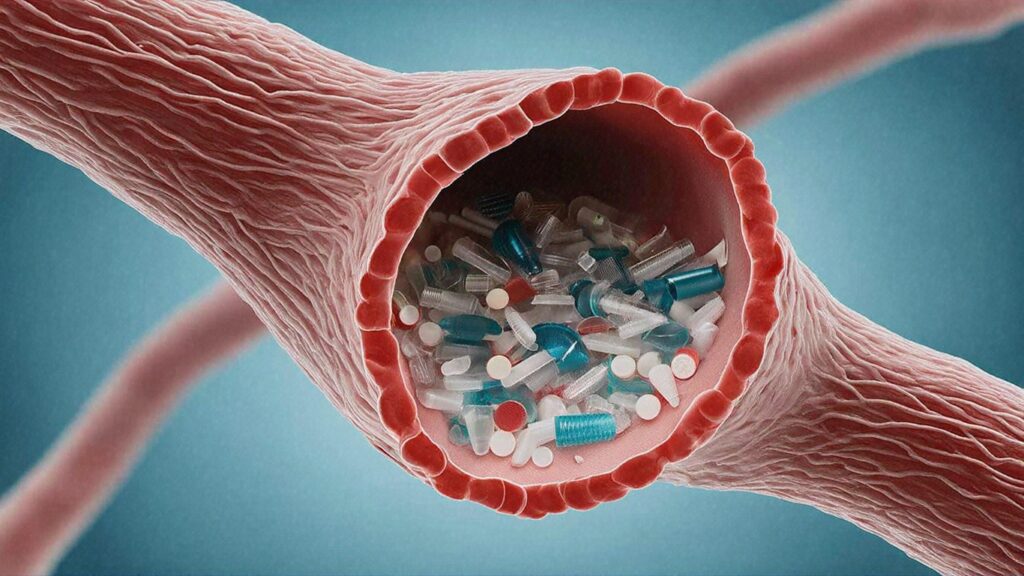

According to new research, microplastics are not just contaminants, but also extremely complex materials that promote antibacterial resistance even without antibiotics.

As global plastic use surges, microplastic pollution is spreading, with wastewater emerging as the main reservoir. At the same time, antibiotic resistance (AMR) is rising worldwide, with environmental factors playing a key role.

“Dealing with plastic pollution is not just an environmental issue. Neela Gross, a doctoral candidate in Professor Muhammad Zaman’s lab at Boston University, said:

Investigation of the development of antibacterial resistance in plastics.

In a new study, researchers have sought to quantify antibacterial resistance at clinically relevant levels and investigate how microplastic properties affect AMR development.

The researchers used a variety of plastic types. Polystyrene, such as packaging peanuts used for transportation. Polyethylene is included in plastic zip top bags. Polypropylene found in crates, bottles and jars).

Sizes ranging from 0.5 mm to 10 micrometers (same scale as typical bacteria) were incubated with E. coli for 10 days.

Every two days, the researchers identified the minimum inhibitory concentration (MICS) needed to kill the infection, or how many antibiotics were needed for four widely used antibiotics to determine whether resistance was growing in resistance.

Microplastics promote the highest level of multi-lag resistance

Researchers have demonstrated that microplastics alone can drive increased AMR development.

“This means that microplastics significantly increase the risk that antibiotics are ineffective against a variety of impact infections,” Gross said.

Previous studies have focused primarily on antibiotic resistance without considering the role of environmental pollutants such as microplastics.

Research using microplastics mainly examined resistance factors such as antibiotic resistance genes (ARGS) and biofilms.

Call to Action: Addressing Microplastic Contamination in AMR Mitigation Efforts

Researchers found that even after antibiotics and microplastics have been removed from bacteria, the resistance induced by microplastics and antibiotics is often significant, measurable and stable.

Ultimately, this means that microplastic exposure may be chosen for genotype or phenotypic properties that maintain antibacterial resistance independent of antibiotic pressure.

Gross concluded: “Our findings reveal that even in the absence of antibiotics, it actively promotes the development of antibacterial resistance in E. coli, and persists resistance beyond antibiotics and microplastic exposure.

“This challenges the notion that microplastics are simply passive carriers of resistant bacteria and highlights its role as an active hotspot for the evolution of antibiotic resistance.”

Given that polystyrene microplastics are known to promote the highest levels of resistance and increase biofilm formation (bacteria survival and drug resistance), the results highlight the urgent need to address microplastic contamination in antibacterial resistance mitigation efforts.

Source link