A new study from the Swedish Institute (RISE) shows that livestock can adapt long-term to virtual fencing and provide new insights into animal behavior.

All across Europe, livestock farmers face the complex challenges of achieving environmental goals, promoting animal welfare, and ensuring food security while adapting to labor shortages.

Traditional methods of livestock management have long relied on physical fences for controlled grazing. These structures are labor intensive for construction, maintenance and repair, while destroying the landscape and often pose a risk of stress and injuries to animals. At the same time, pressure on the agricultural sector is increasing, from environmental regulations and biodiversity goals to demanding more efficient production and higher animal welfare standards.

Since launching commercial launches five years after the foundation in 2011, Nofence’s virtual fencing system has emerged as a transformational tool for the livestock management and the agricultural sector as a whole. By replacing physical barriers with GPS-enabled collars that use audio cues to run through pastures, the technology provides farmers with flexibility while supporting natural grazing behaviour. It reduces the need for physical labor, minimizes the risk of injury, and creates new possibilities for managing livestock across challenging terrain and conservation areas.

Research has already demonstrated how livestock adapt to virtual fencing during training periods, and animals quickly learn to respond to audio cues, minimizing stress. Based on this solid foundation, new research is now beginning to provide insights into the long-term adaptation of livestock to technology, showing how behavioral changes can be enhanced over time.

Virtual fencing at a glance

The NoFence system combines GPS-enabled colors with a user-friendly mobile app to make it easy for farmers to set and adjust virtual boundaries and provide the flexibility to manage grazing areas in real time.

As the animal approaches the boundary, instead of an immediate correction, the collar plays a series of audio cues that increase in pitch as the animal approaches, quietly responding and spinning. Only when repeated cues are ignored, collar provides a mild electrical pulse, half the strength of the physical electric fence, as a last resort. Over time, these correctional pulses become increasingly needed, leading to a more relaxed grazing environment.

To support this learning process, Nofence has designed a training process that ensures the highest level of animal welfare. The animal is first introduced into the pastor’s collar, with three sides surrounded by physical fencing and the fourth covered by virtual boundaries. During this phase, the colour operates in “teach mode.” Even small changes in directions will turn off the audio cue and help the animal make connections so that it can be quickly and predicted. Most animals adapt quickly, indicating that 96% of the interactions are resolved without the need for pulse after the first initial training stage.

Livestock are very social and their reactions often affect the rest of the group. Once several animals learn to respond to audio cues, others will soon follow, enhancing group learning and reducing stress throughout the pack. This synchronized behavior means that animals adapt not only individually but collectively, creating a stable, predictable grazing environment. Over time, this group will strengthen the association between sound and boundaries, further minimizing the need for correction, and helping to maintain a calm, low-stress atmosphere throughout the group.

Research-backed welfare results

More and more independent studies confirm that virtual fencing is effective and welfare-friendly. Several studies compared the system with physical electrical fencing and found no significant differences in stress indicators such as cortisol levels, but no adverse effects on behavior or weight gain.

The study published in Animal¹ examined the use of Nofence Collars with heifers grazing in mountain pastures in Switzerland. This study found that virtual fencing is as reliable as electrical fencing in preventing escape, and that animals are consistently adapted to the system. The activity patterns, including circadian rhythms, remained very stable, indicating that animal welfare was not compromised even in challenging situations in alpine environments.

Furthermore, a comprehensive review of veterinary science frontiers highlighted the need to assess welfare impacts through both physiological indicators (e.g. cortisol levels) and behavioral responses. In this review, we concluded that animals adapt normally without adverse consequences when systems are designed to provide predictability and control in the environment.

Together, these findings provide consistent evidence that Nofence provides greater flexibility in grazing methods while maintaining animal welfare. However, most of this study focuses on training periods and short-term adaptation.

To enlarge this picture, researchers at the Swedish Institute (RISE) collected and analyzed a two-year data set from animals wearing Nofence collars, helping to address key gaps in scientific evidence.

Long-term animal adaptation

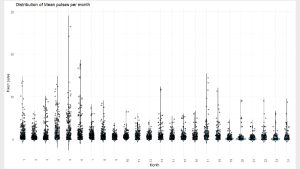

Their analysis provides an initial detailed perspective on long-term adaptation, demonstrating how animals use the system to refine their behavior over months and years. Looking at the two-year dataset, researchers observed a steady decline in the number of pulses fed (Figure 1), indicating that animals were increasingly responding to sound cues only, rather than receiving correction. The number of animals involved changes during the study period and further research is needed to confirm these trends, but the results are consistent with those consistently shown by farmers and previous trials. After being trained, livestock will quickly learn to operate the system.

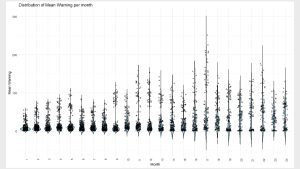

The same dataset indicates that warnings increased over time. This is a positive indication that animals encountered virtual boundaries more frequently (Figure 2) and choose to listen and respect the escalating audio cues. Instead of violating boundaries, they retreated and demonstrated the ability of colour to guide actions primarily through sounds rather than correction.

Monthly per animal warning signals

As the whole is considered, Rise’s findings highlight that Nofence’s technology is not effective in the short term. Over time, livestock continue to coordinate responses, relying heavily on audio cues, demonstrating evidence of long-term adaptation to virtual fencing.

Additionally, success rates improved month by month (Figure 3), reinforcing pictures of long-term behavioral changes. Animals not only learned the connection between sounds and boundaries during training, but continued to reinforce this behavior over time.

The data also show an occasional surge in pulsation or infringement after long-term stability. The exact reason remains unknown, but these anomalies may be related to the introduction of new, untrained animals inheriting collars, or seasonal changes in pasture layout. Importantly, such outliers proved to be temporary and stability returned as the animals adapted to the system.

Conclusion

Virtual fencing has already proven as an essential tool in one system for farmers who control the grazing of cattle, sheep and goats and combine animal welfare, flexibility and sustainability. Rise’s latest findings show that not only does livestock adapt quickly, they continue to improve their behavior over time, increasingly relying on audio cues rather than revisions.

In addition to existing research, this long-term evidence strengthens how it supports both animal well-being and the practical needs of farmers, whilst contributing to more sustainable land management.

reference

P. Fuchs, CM Pauler, MK Schneider, C. Umstätter, C. Rufener, B. Wechsler, RM Bruckmaier, M. Probo, Effectiveness of Virtual Fencing in Mountain Environments and Native Behavior and Welfare of Native Farmers, Animals, Vol. 19, No. 8, 8, 2025, 101600, ISSN 1751-731,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.animal.2025.101600 Caroline Lee, Dana LM Campbell, Welfare Impact of New Virtual Fencing Technology, Frontiers of Veterinary Medicine, 8-20211

https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.637709

This article is also featured in Animal Health Special Focus Publication.

Source link