Psilocybin, the main psychoactive ingredient in magical mushrooms, extends the lifespan of human cells, laboratory studies suggest. Researchers also found that psychedelic compounds slow certain features of aging in older mice while improving fur quality.

The findings published July 8th in Journal NPJ Aging provide the first experimental evidence of the potential anti-aging properties of psilocybin.

“This study offers a unique view of the potential of psychedelics to promote healthy aging and a provocative mechanism that explains how they do it,” said Scott Thompson, a professor at the University of Colorado School of Psychiatry, who was not involved in the study.

You might like it

But “a lot of additional work is needed to advance these findings, ensuring that they are applicable and adaptable to human health,” Thompson said.

Recently, research has explored the potential treatment of psilocybin to treat a variety of conditions, including anxiety such as Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and neurodegenerative disorders. Some of this research have led to clinical trials with promising results. However, researchers have not yet fixed exactly how psychedelics achieve their benefits.

One theory, called the “Psilocybin telomere hypothesis,” suggests that psilocybin preserves the length of the telomere, the protective cap of repetitive DNA sequences at the edge of the chromosome. Researchers have long understood that telomeres become shorter with age, and the rate of shortening correlates with ageing.

Related: “Magic Mushroom” Compounds Create Hyper-Connected Brains to Treat Depression

So, if psilocybin protects the length of the telomere, can it also slow down aging?

To investigate, senior author Dr. Louise Hecker, an associate professor at Baylor School of Medicine in Houston, administered various doses of psilocin that breaks down into the body, and isolated human lungs and skin cells. The team found that psilocin expands cell lifespan by up to 57% depending on the dose given.

Pylocin also preserved reduced cellular telomere length and levels of oxidative stress, or accumulation of reactive molecules. At the same time, the levels of SIRT1, a lifespan-related protein, were increased.

In short, psilocin made cells look like young cells, Hecker told Live Science. Hecker’s research involves testing the effects of aging on the body and that everything she knew was “just worked.” “I was flooring the data.”

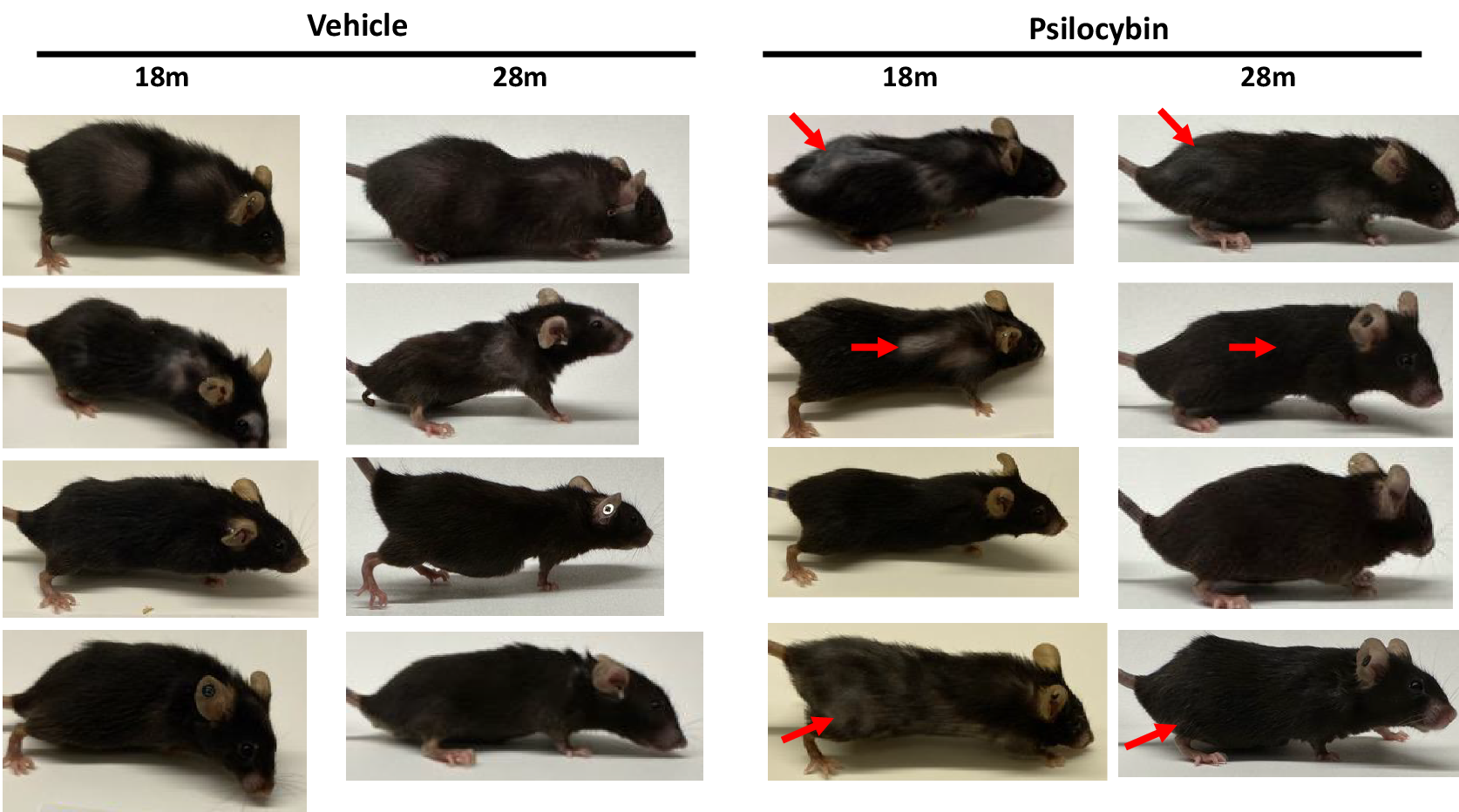

The team then continued to study the effects of psilocybin on female mice for approximately 19 months. This is when humans are in their early 60s. Mice were administered monthly psilocybin for 10 months. At the end of that period, 80% of treated mice were still alive, compared to only 50% of the untreated group. Treated mice also showed hair growth that previously had bald spots, with white hair once reverting to brown.

“It’s exciting to be able to end this intervention and have such a dramatic impact,” Hecker said.

In general, psychedelics are known to alter the behavior of the immune system and the body’s stress resilience. Both can affect organ health, Thompson said. “What’s new in this study is the provocative suggestion that changes in telomere length (a key regulator of DNA replication) can be produced by psychedelics.”

A major limitation of the study is that the drug doses used in lab mice are much higher than those normally administered to humans, Thompson said. That said, Hecker argues that the comparison does not take into account the much faster metabolism of mice, thus reducing the time that psychedelics operate in animals.

The findings set the stage for investigating psilocybin as a treatment for aging and age-related diseases, Hecker said. Future research should investigate the optimal dose and potential risks for use in humans, she said.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide medical advice.

Source link