What if the first sample of Mars rocks is deliberately drawn back to Earth, which landed in Beijing rather than Houston?

The scenario is once overstated and approaches reality. The US-led Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission – designed as a carefully curated geological cache capstone of geological samples scooped up from Mars’ Jezero Crater, long flagged as a top priority in planetary science – stalled.

You might like it

At the same time, designed as a more sophisticated effort aimed at collecting fewer, carefully selected samples, China’s Tianwen-3 mission is on track for the 2028 launch with a plan to the Earth in 2031. With China’s launch window approaching, experts say NASA may already have lost the opportunity to move forward.

“I don’t think it’s a competition anyway because I already know enough about the issues of MSR and its budget,” Chris Impey, an astronomer at the University of Arizona who is not directly involved in the sample restitution program in either country, told Live Science. With NASA’s mission already far enough away, with cached samples and major hardware designed or built on Mars, pivoting to the nasty and inexpensive alternatives that now meet the original mission’s time frame is “simply impossible.” “They’re sticking to the plans they have.”

The scientific reward is immeasurable. By returning a sample of Mars, labs on Earth can perform analyses that cannot be achieved with rover-based instruments, such as exploring atomic and molecular scale rocks, searching for organic compounds, and even scanning fossilized microorganisms.

Such a job can ultimately prove whether Mars once took a life or confirm that it is always barren. Both results revolutionize planetary science. But like many of the first in the universe, science is just part of the story.

“Undoubtedly, the initial existence has some geopolitical value, and the value in that respect comes from the public perception of the initial existence,” Gerald Vanbell, director of Science and Science at Lowell Observatory, Arizona, who is not directly involved in the sample return mission of either country, told Live Science. “The idea that one mission is better in terms of the outcome will probably get lost in the mix. That’s a shame.”

Can NASA catch up?

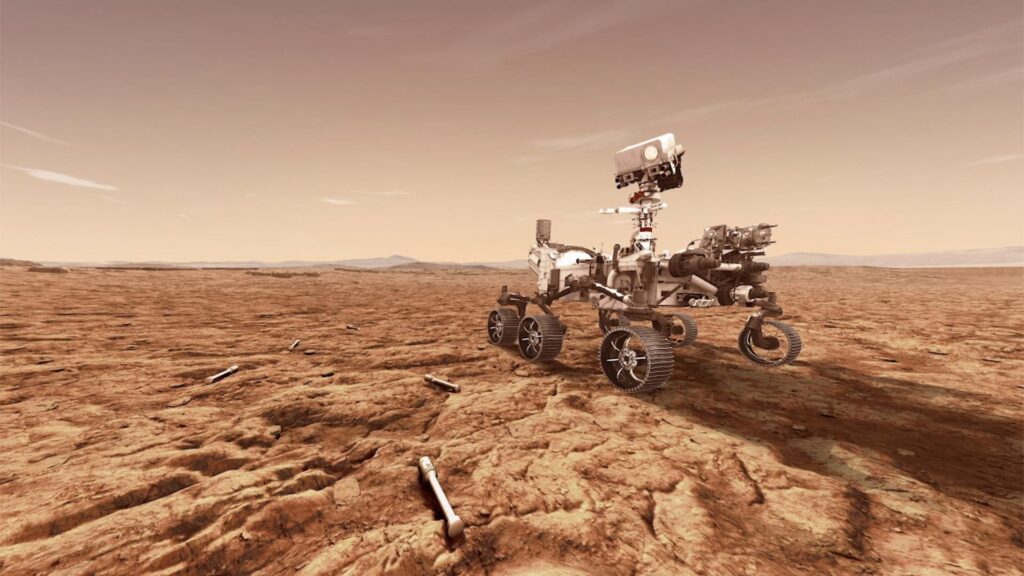

Since 2020, NASA’s patient rover has been excavating and caches dozens of samples in Jezero Crater, the Ezero Crater. This revealed what the agency calls “the clearest sign it has ever found on Mars.” Scientists argue that such carefully curated rocks still represent humanity’s best chance of determining whether Red Planet is the home of life to date.

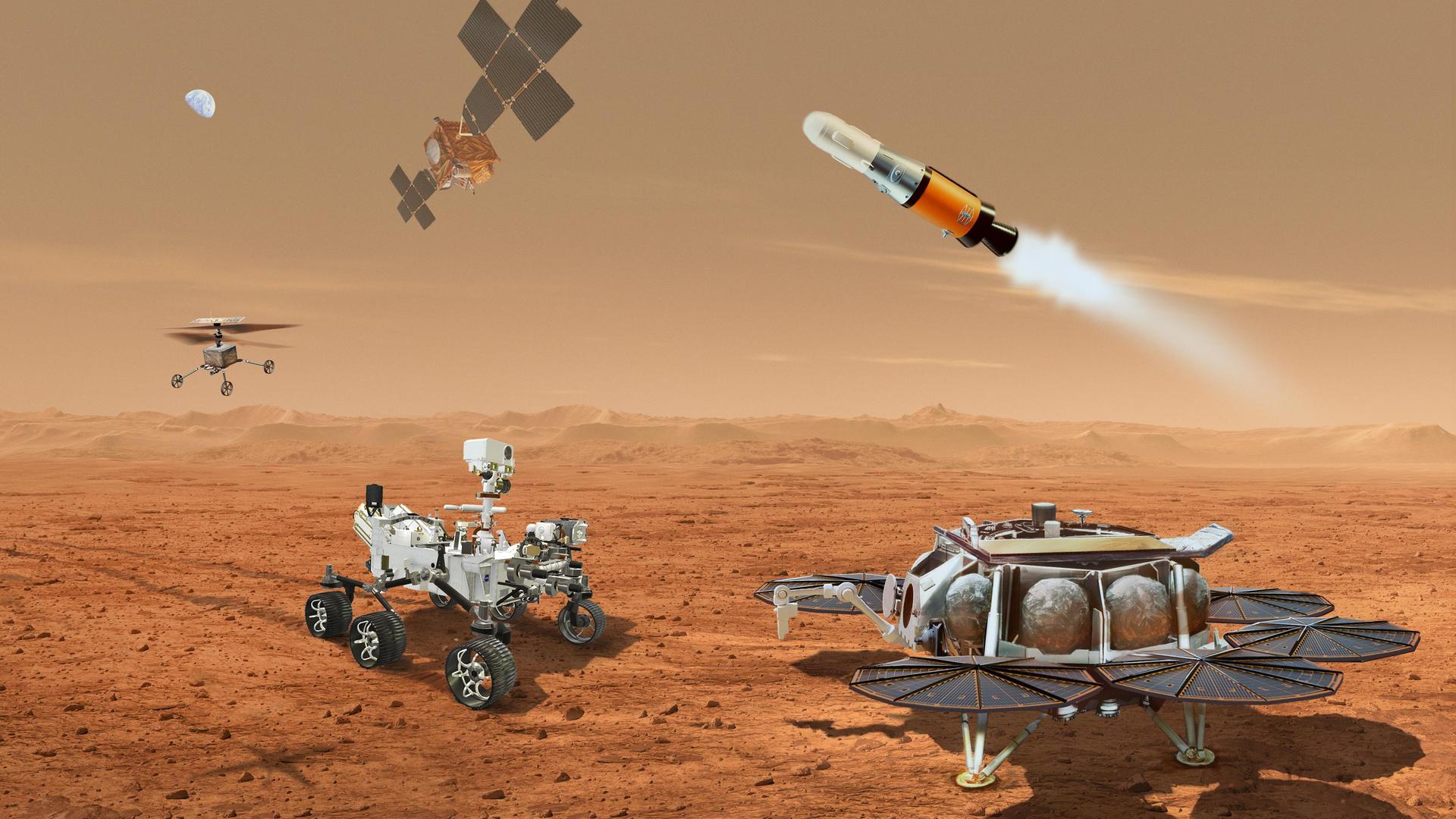

But bringing them home proves elusive. The US-led MSR, a joint project with the European Space Agency, was conceived as a high-stakes chain for complex handoffs. The Cache of Patience was transferred to the Ascension Vehicle on Mars by a robotic arm and moved into orbit for capture by a Return Space spacecraft.

You might like it

Even after the “Fetch Rover” plans were later dropped in favor of a pair of miniature helicopters, the choreography remained astronomically expensive. With the cost exceeding $11 billion and the timeline slides into 2040, NASA declared its plans unacceptable in 2024.

“Maybe if the US had to rethink that, they might have cast a slightly different path they could have done on a simpler mission at first — maybe,” Van Bell said.

Earlier this year, NASA outlined two scaled back alternatives. Either one needs to be released around 2030 and a $300 million commitment from Congress must go smoothly for around 2035-2039 to return around 30 Mars samples.

Still, Impey suspects that NASA can regain the lost ground. “Even if they get the money they want now, I don’t think they can accelerate their timeline,” he said.

In contrast, China’s Tianwen-3 bets on a self-contained mission that has been demonstrated by the recent moon mission that returned a Lunar sample in Thang’e-5 in 2020.

The Tianwen-3 calls for two launches carrying a lander equipped with drills, robotic arms and helicopter scouts, the other carrying an Orbiter Returner spacecraft. Using a “glove and go” approach, Lander collects samples and loads them directly into its ascending vehicle. About two months later on the surface, the rocket-powered stage meets an orbiter returner in Mars orbit, bringing about a pound (500 grams) of material back to Earth.

China’s mission is to target geologically lower and more diverse landing sites than Jezero, chosen for safety rather than scientific promises. This means that the sample may be more obvious than the cache of perseverance. Still, the Tianwen-3 is more likely to remain on the schedule as it is embedded in China’s long-term space strategy. It was healthyly funded, already returning samples of the moon, building a space station, setting permanent lunar foundation targets by 2035, and serving on missions to Mars by 2050.

“[China’s] The timeline is decades, but the NASA timeline is pretty much resolved as we see it.

A new sputnik moment?

The NASA obstacles are not purely technical. The White House is proposing sudden cuts. It nearly halved NASA’s scientific budget, cutting overall funding by 24% from $24.8 billion to $18.8 billion. If enacted, it marks the steepest year-long cut in NASA history, deeper than the reductions that followed the abolition of the Apollo program in the 1970s.

Next year will be decisive, Impey said. If cuts are enacted, they not only put MSR at risk, but also cause wider reductions across active observatory and planetary probes.

“That’s devastating,” Impey said. “It’s a cliff where they could fall, and if they fell off that cliff, the US-led MSR efforts certainly won’t happen for decades.”

If China first returns a sample of Mars, the symbolism reflects a potentially new Sputnik moment. In 1957, the launch of the Soviet Union’s first satellite surprised the United States, spurred the creation of NASA, fostering large-scale investments in science and engineering education, and accelerated the space race that ultimately reached its peak at Apollo Moon Landings a decade later.

Planetary scientists wanting to know about Mars’ past habitats have emphasized that, rather than seeing the plug being pulled completely, the US-led Mars sample return mission wants to be successful, even if it has to be delayed.

“Can I answer the question of what is important, whether there was life on Mars, or if that was the case?” Impey said.

However, a single mission to solve that question is not guaranteed, he warned. Each returns only a small cache of rocks from a single region of a vast and complex planet. It makes it even more important that both NASA and China succeed in sample return plans, as their efforts could provide a complementary part of the puzzle.

“If you bring home the perfect rock, you’ll get lucky, yes,” Impey added. “There is still a chance that a single shot sample from one location will return.

Source link