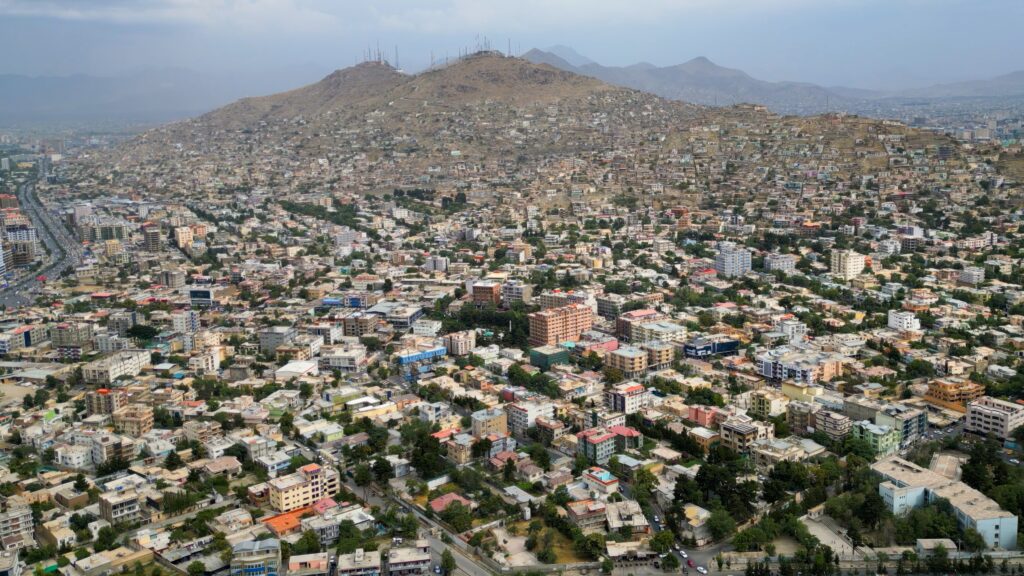

Recent reports show that Kabul, Afghanistan, is at risk of becoming the first modern capital to run out of water.

Kabul is depleted due to a combination of factors, including climate change, poor water resource management, rapid urbanization, and an expander population of around 5-6 million people.

Humanitarian NGO Mercy Corps discovered that in April the water crisis in Kabul reached a turning point, releasing faster than aquifers could be replenished, and problems surrounding water affordability, pollution and infrastructure.

You might like it

In June, one Kabul resident told the Guardian that quality well water was not available, but last week another resident told CNN he didn’t know how his family would survive if things got worse.

The water problem in Kabul is not new and has been steadily worsening for decades. The report highlighted that it has been exacerbated since August 2021 by a decline in humanitarian funding in Afghanistan.

“Without a major change in Kabul’s water management dynamics, the city will face unprecedented humanitarian disasters within the next decade, but perhaps much sooner,” a representative from Mercy Corps wrote at the end of the report.

Related: “Existential Threats Affecting Billions”: Three-quarters of Earth’s Land have been permanently dried over the past 30 years

The new report is based on previous research by the United Nations (UN). This found that Kabul’s groundwater is at risk of disappearing by 2030, and about half of Kabul’s boreholes were already dry. Currently, extraction exceeds approximately 1.5 billion cubic feet (44 million cubic meters) of natural refills each year, according to the report.

Mohammed Mahmoud, a water security expert who was not involved in the report, told Live Science that Kabul was clearly in the midst of a water crisis.

“The fact that water extraction now naturally charges tens of millions of cubic meters each year, and that half of the urban groundwater wells are already depleted, are indicative of a system of collapse,” Mahmoud said in an email.

Mahmoud is the CEO of Climate and Water Initiative NGOs and is the lead in Middle East Climate and Water Policy at the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health. He described the findings in the report as “very uneasy” and noted that he was also interested in the rapid decline in Kabul’s water table and the growing number of residents forced to spend a significant portion of their income on access to water.

Mercy Corps reports that levels of aquifers in Kabul have fallen by about 100 feet (30 m) over the past decade, with some households spending up to 30% of their income on water.

“This isn’t just an environmental issue, it’s a public health emergency, a livelihood crisis, and an impending trigger for potentially large human displacement,” Mahmoud said.

Global Issues

Water shortages are a global problem affecting many different regions. Water resources have been expanding in recent decades, along with environmental factors such as climate change that increase the frequency and severity of droughts, while human factors such as population growth that increase the demand for water.

A 2016 survey published in Scientific Reports found that between the 1900s and 2000s, the number of people facing water shortages increased from 240 million to 3.8 billion, or from 14% to 58% of the world’s population. Areas at particularly high risk of shortages include North Africa, the Middle East and South Asia.

“What’s happening in Kabul reflects the wider trends seen across water-stressed regions around the world, especially in the Middle East and North Africa,” Mahmoud said. “Groundwater overuse has ramped in many parts of the region, and has not kept up to the extraction of aquifers in groundwater charging speeds. Climate change reduces and changes rainfall patterns, increasing the frequency and severity of droughts while further limiting freshwater generation and groundwater charging.”

The new report highlights that Kabul is on the verge of becoming the first modern capital to run out of water, but it is not the first major city that faced such an existential water-related threat, and based on current trends, it is not the last.

In 2018, South Africa’s legislative capital, Cape Town, nearly drained water during the drought, narrowly avoiding having to turn off taps thanks to tight water restrictions and water-saving campaigns. This situation worsened in 2019 in India’s Chennai city, with all four major reservoirs exhausted, severely restricting water supply, and putting the city in danger.

Mahmoud noted that water shortages have serious socioeconomic consequences, affect agriculture and food security, increase the cost of living, and in extreme cases, cause mass migration and evacuation of people.

“We need to have more powerful investments in sustainable water management, robust water infrastructure and better governance to begin addressing the issue of water scarcity,” Mahmoud said.

Source link