About 4.5 million years ago, the sun passed close to two extremely bright stars, flooding nearby space with their radiation. And that encounter left a ghostly scar that astronomers can still detect today, a new study says.

The researchers say this close encounter could help solve decades-old mysteries, such as why the space around the solar system is much more energetic than models predict and contains an excess of ionized helium.

you may like

These stars now mark the front and back legs of Canis Major (the Great Dog), which is more than 400 light-years from our solar system. But about 4.5 million years ago, when the stars passed through our solar system, they were younger, hotter, and brighter. Their passage may have also coincided with the time when Lucy, a surprisingly complete fossil of an early human ancestor discovered in Ethiopia in 1974, was walking the Earth.

“They’re not coming straight at us… but it’s close,” Schall told Live Science. “If Lucy and her friends had looked up and noticed the stars, the two brightest stars in the sky would not have been Sirius, but Beta and Epsilon Canis Major.”

The findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal on November 24th.

Mysteries that remain

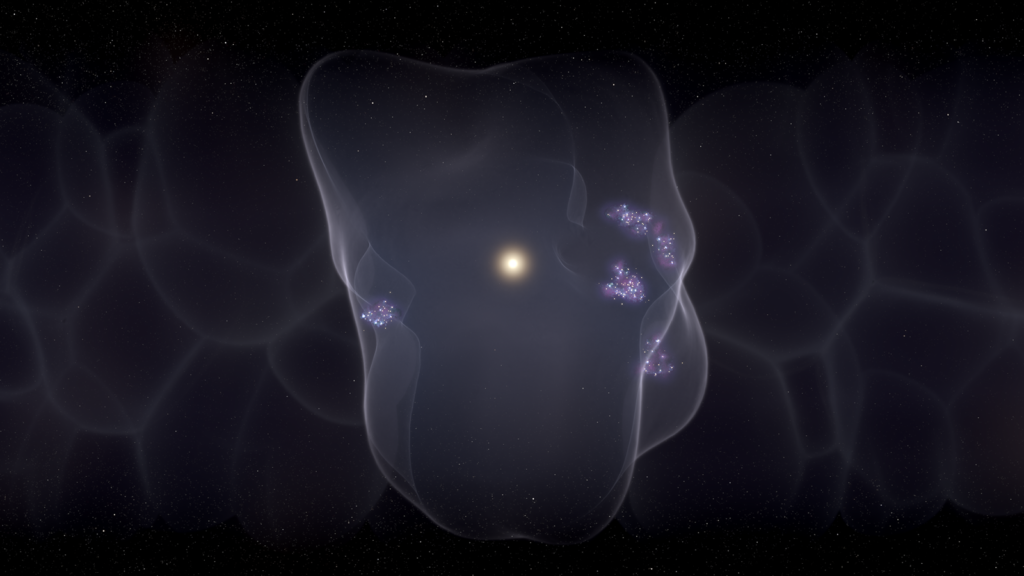

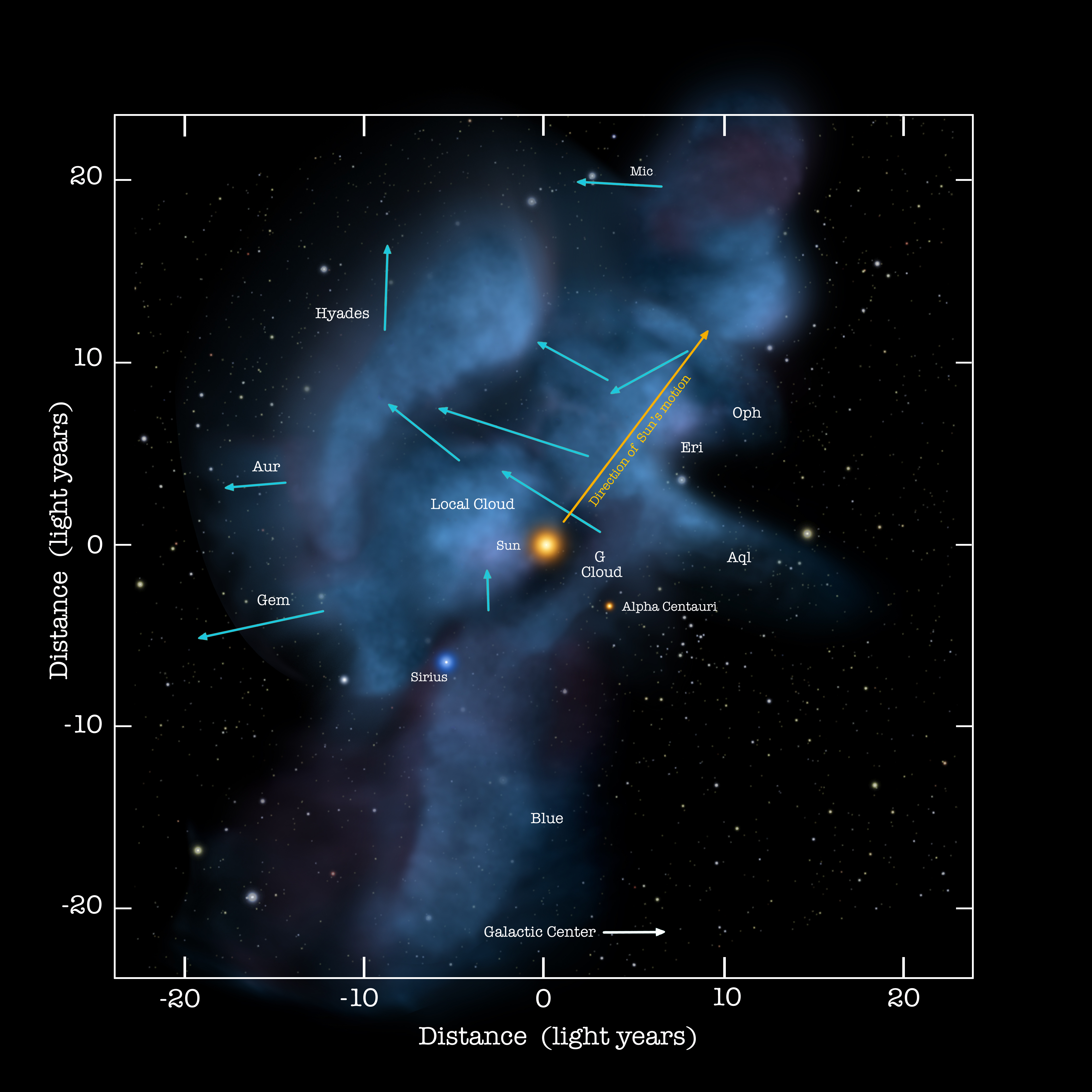

Currently, our solar system floats through a diffuse patchwork of more than a dozen nearby gas and dust bodies called the local interstellar medium. This material is made primarily of hydrogen and helium and extends approximately 30 light-years from the Sun.

Astronomers believe these clouds were formed over millions of years by shock waves from exploding stars in the Scorpio-Ophiuchus region, a rich population of massive stars about 300 light-years from Earth. The shock wave compressed interstellar gas into the thin local clouds seen today.

Observations dating back to the 1990s, including observations by NASA’s now-retired Extreme Ultraviolet Explorer, have revealed that this region is unusually ionized. In particular, helium atoms are stripped of electrons at nearly twice the expected rate compared to hydrogen.

This imbalance puzzled astronomers because helium requires more energetic radiation to ionize than hydrogen. This makes it difficult to explain the increase in ionization solely by solar radiation. The sun’s radiation does not extend far beyond the solar system.

you may like

To investigate this mystery, Schall and his colleagues used measurements from the European Space Agency’s Hipparcos satellite, which mapped the locations of more than 1 million stars over a four-year mission that ended in 1993, to calculate the properties and ultraviolet output of Beta Canis Major and Epsilon.

Knowing how far apart the two stars are now (about 400 light-years) and how fast they are moving, the researchers were able to trace the stars’ trajectories back in time and recreate their passage as they approached the solar system about 4.5 million years ago.

“It’s like a dance floor.”

The researchers’ models show that the wispy local cloud would have been intensely ionized by the two stars’ radiation, at levels up to 100 times stronger than what is seen today. Over time, the gas is thought to have slowly returned to a more neutral state through a process called recombination, where free electrons recombine into ions and become atoms.

“This is like a dance floor,” Schall told Live Science. “Protons and electrons are dancing around, sometimes together, sometimes apart.”

But that process takes time, and continued exposure to radiation from other sources leaves the gas partially ionized, Schall said. Astronomers had previously identified other sources of ionizing radiation, including three nearby white dwarfs: G191-B2B, Feige 24, and HZ 43A. These are the remains of compact stars known to emit strong ultraviolet light. The researchers also pointed to local bubbles, vast regions of hot gas ejected by supernovae that extend about 1,000 light-years around the solar system.

“Higher-energy photons preferentially ionize helium,” he says. “That’s the bottom line.”

pieces come together

Schall said that although astronomers have had reliable data on the star’s motion for decades, they have only recently been able to solve this problem. Advances in ultraviolet and X-ray observations made possible by suborbital rocket flights, improved models of stellar evolution and atmospheres, and the computational power needed to run them are finally allowing researchers to connect the dots.

“The problem was ripe in the sense that all the pieces of the puzzle were starting to come together,” Schall said.

The results of this study may have an impact even close to home. Local clouds help protect Earth from high-energy particles that wander around the galaxy and that scientists suspect could erode Earth’s ozone layer.

However, the sun is not expected to remain inside these clouds forever. Researchers estimate that it could leave its protected area within just 2,000 to tens of thousands of years, drifting throughout the galaxy. “Then we would be exposed to a lot of radiation,” Schall said.

Looking ahead, Schall said understanding how the atoms in the wispy local clouds changed between more charged and more neutral states as radiation rose and fell as the two stars approached, passed by, and moved away from the solar system is still part of the larger puzzle researchers are putting together. “The problem is not completely resolved, but I think we are moving in the right direction,” Schall said.

Source link