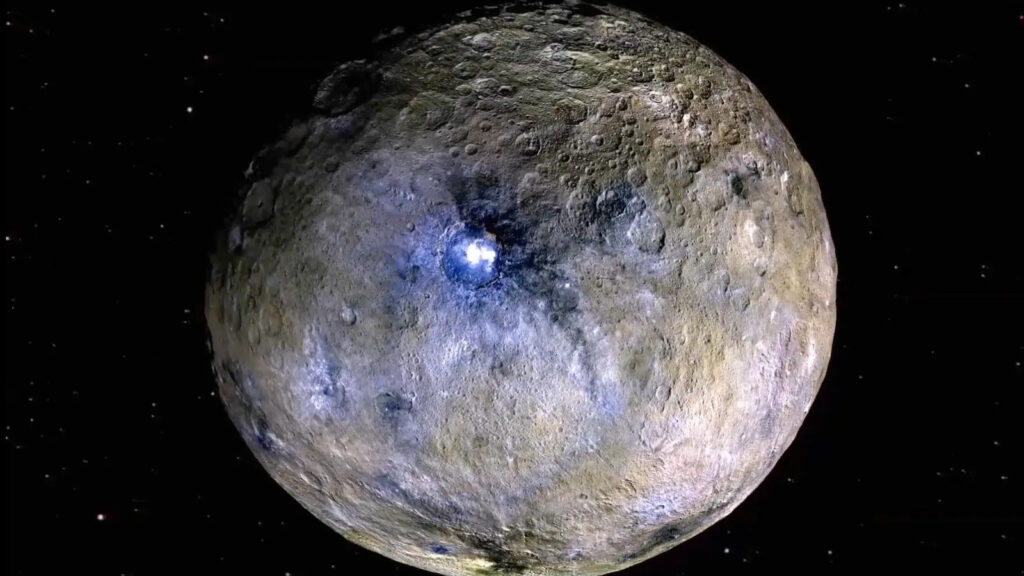

New NASA research suggests that Ceres (the dwarf planet closest to Earth) may have once had an ancient “power supply” that could trigger the evolution of extraterrestrial life forms in the hidden oceans of a small world.

Ceres is the largest object within the main asteroid belt of the solar system, between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. The little world is about 600 miles (950 kilometers) wide and the moon is about a quarter of the diameter, so it’s not so big enough to be considered a planet. But it’s large enough to be considered a “small wharf planet” like Pltune, which lost its full planetary state in 2006.

Our universe neighbours are five official dwarf planets, others awaiting proper recognition by the International Astronomical Union, and many more discoveries are expected in the coming decades. However, Ceres is the only one in the internal solar system. The remaining dwarf planets, including Haumea, Makemake and Eris, are located well beyond Neptune’s orbit.

You might like it

In recent years, scientists have learned a lot about Ceres thanks to NASA’s Dawn Probes that visited the object between 2014 and 2018. One of the most interesting finds from the Dawn Mission is that the giant space rocks are likely to be a water world. Other studies suggest that this underground ocean could also include organic carbon, a key component of all life on Earth.

But up until now, scientists thought that life would not appear in Ceres because there is no energy source to start life on the dwarf planet.

However, in a new study published on August 20 in the Journal of Science Advancements, researchers have revealed that this is not always the case.

Related: James Webb’s Telescope Finds the Potential Conditions of Life on Two Dwarf Planets Beyond Neptune

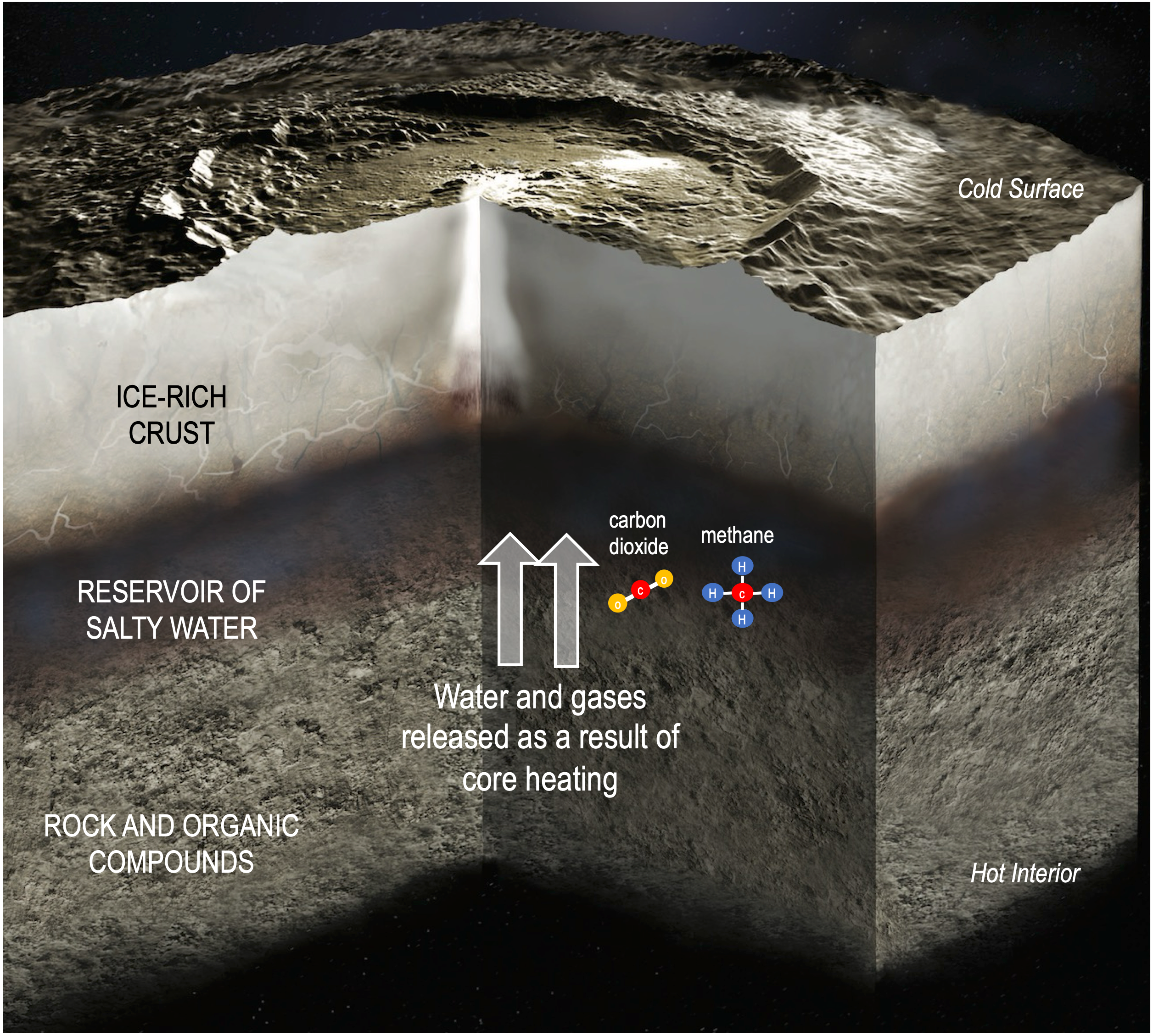

The research team created computer models based on data collected by the Dawn Mission, simulating how the rocky body cores changed over time. This revealed that the internal organs of the dwarf planet were used to release large amounts of energy, perhaps in the form of heat.

This is also a researcher at Samuel Courville, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University and a former intern at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Institute, research author Samuel Courville, a researcher at Samuel Courville, a researcher at Arizona State University, and a researcher at the lead author of the researcher Samuel Courville, a former intern at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Institute, said in a NASA statement.

Researchers believe that Celes’ core once released a significant amount of heat from the gradual decay of radioisotopes. The team believes that this heating has continued five or two billion years since the giant rock was created. At the hottest point, the core likely reached around 530 degrees Fahrenheit (280 degrees Celsius), the researchers wrote.

This is not the first time a scientist has proposed that Ceres has a radioactive core. However, this is the best evidence that it has produced enough heat to potentially support life.

In addition to heating the underground oceans of the d-star planet to habitable temperatures, radiation may have caused jets of hot mineral-rich water to jump from the ocean floor, similar to the Earth’s hydrothermal ventilation system that supports diverse microbial communities in the sea crushed dark depths.

“On Earth, when hot water from deep underground mixes with the ocean, the result is often a buffet for microorganisms, an east feast of chemical energy,” Coolville said.

Astrobiologists suggest that similar systems could support extraterrestrial life in other water worlds in the solar system, such as Enceladus on Saturn’s moons and Titan, and Moons Europe and Ganimede in Jupiter.

However, since Ceres’ radioactive core died about 2.5 billion years ago, alien microbes are likely to disappear from the cold, so there is no chance that today’s dwarf planets will support their lives today.

Source link