Determining how much water there is across the landscape is not easy. Only 1% of the Earth’s freshwater is on the surface and relatively easy to see and measure. But below that, measurements vary widely, depending on the depth of the water table and the porosity of the ground, which can’t be seen directly.

Reed Maxwell, a hydrologist at Princeton University, likes to think of groundwater as a savings account, with rainfall, snow and surface water used as checking accounts for short-term water management needs, which ideally should accumulate larger sums over time.

you may like

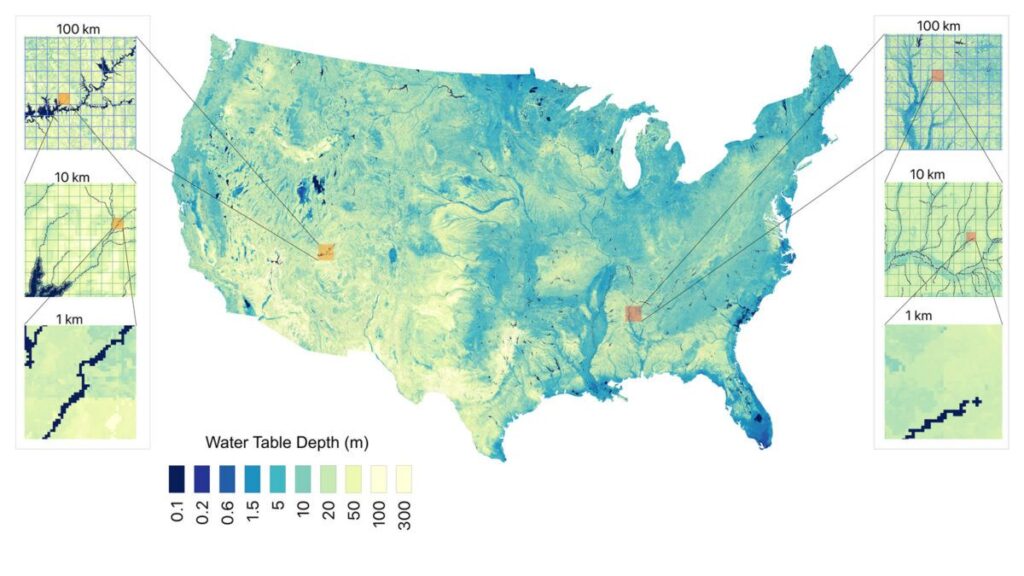

But a new groundwater map by Maxwell et al. provides the highest-resolution estimate to date of groundwater volume in the continental United States, about 306,500 cubic kilometers. That’s 13 times more water than all the Great Lakes combined, and nearly seven times more than all the earth’s rivers release in a year. This estimate, made at 30-meter resolution, includes all groundwater to the deepest depth for which reliable porosity data exist, 392 meters. Previous estimates using similar constraints ranged from 159,000 to 570,000 cubic kilometers.

“This is definitely a step forward from some things we have done before. [mapping] “They’re looking at much better resolution than we’ve seen before, and they’re using some interesting techniques,” said Grant Ferguson, a hydrogeologist at the University of Saskatchewan who was not involved in the study.

Well, well, well

Previous estimates of groundwater volume were mainly based on well observations.

“That’s what’s really weird about groundwater in general,” said Laura Condon, a hydrologist at the University of Arizona and co-author of the paper. “We stick these pins underground where the well is and measure the depth of the water table. That’s what we have to work with.”

However, not all wells are regularly measured. For obvious reasons, locations with more groundwater tend to have more wells, while data for areas with less groundwater is scarcer. Also, although a well represents only one point, the depth of the water table can vary greatly over short distances.

The researchers used these data points and knowledge of the physics of how water flows underground to model the depth of the water table to a resolution of about 1 kilometer. They also used satellite data to capture large-scale trends in water movement. But those data have low resolution, such as data from NASA’s GRACE (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment) tellus mission, which has a resolution of about 300 kilometers, about 10,000 times coarser than the new maps.

To demonstrate the value of high-resolution data, the team showed what happens when the overall map resolution is lowered from 30 meters to 100 kilometers (the spatial resolution of many global hydrological models). The resulting more pixelated map estimated the water area to be just over 252,000 cubic kilometers, an 18% underestimate compared to the new map.

you may like

In addition to determining the amount of groundwater at high resolution, the new map reveals more nuanced information about known groundwater sources.

For example, approximately 40% of the land in the contiguous United States exhibits water table depths less than 10 meters. “That 10-metre range is where groundwater, vegetation and surface interactions are possible,” Condon said. “So this really shows how these systems are connected.”

prejudice against goodness

The new study used direct well measurements and satellite data (about 1 million measurements taken between 1895 and 2023), along with maps of precipitation, temperature, hydraulic conductivity, soil quality, elevation, and stream distance. The scientists then used that data to train a machine learning model.

In addition to being able to quickly classify so many data points, Maxwell pointed out another benefit of the machine learning approach that may sound unexpected: its bias. Early groundwater estimates were relatively simple and did not take into account hydrogeology or the fact that humans themselves pump water from underground. The team’s machine learning approach was able to incorporate that information because evidence of groundwater pumping was present in the data used for training.

“When you hear about bias in machine learning, it usually has a negative connotation, right?” Maxwell said. “After all, if we can’t disentangle the signals of groundwater pumping and groundwater depletion from the roughly 1 million observations we used to train this machine learning approach, the machine learning was implicitly learning that bias. … The machine learned the pumping signal, and it learned the human depletion signal as well.”

Maxwell and other researchers hope the map will be a resource not only for regional water management decision-makers, but also for farmers making irrigation decisions. Condon added that he hopes this will raise awareness about groundwater in general.

“Groundwater is literally everywhere at all times,” she said. The map says, “No matter where you are, it’s going to be buried. Some places are 300 meters deep, some are 1 meter deep. But no matter where you stand, if you dig, there’s water somewhere.”

This article was originally published on Eos.org. Read the original article.

Source link