Digital analysis of a perfectly preserved nasal bone in a bizarre-looking Neanderthal skull reveals that long-standing theories about Neanderthal noses don’t pass the sniff test.

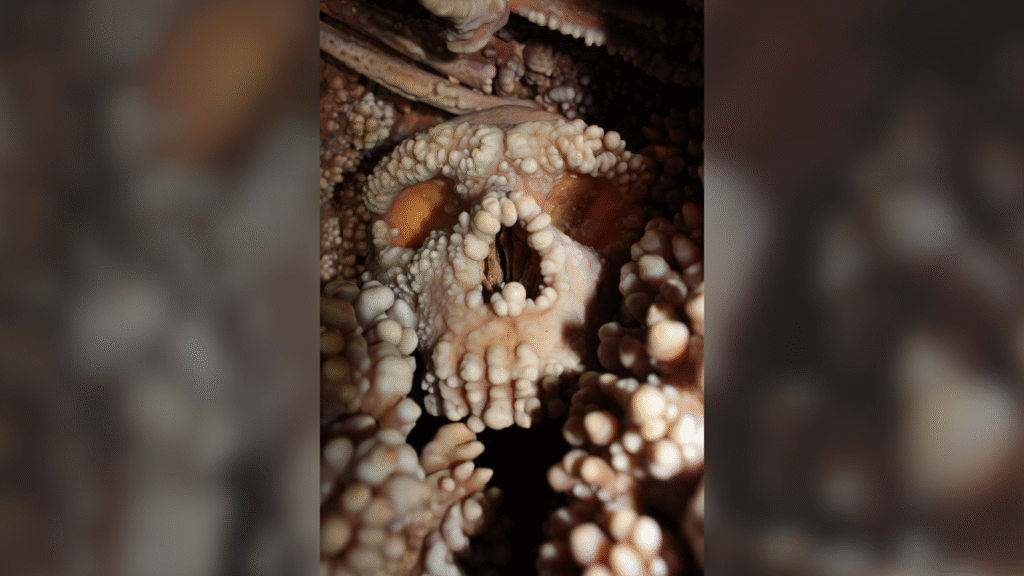

This skull belongs to the Altamura man, one of the most complete and well-preserved Neanderthal skeletons ever discovered. Speleologists discovered it in 1993 while exploring a cave near the town of Altamura in southern Italy. Altamuraman has not been removed from the cave to prevent damage to the bones, as it is covered with a thick layer of calcite, or “cave popcorn.” This Neanderthal man likely died at the exact location where the skeleton was found, between 130,000 and 172,000 years ago.

you may like

“The general shape of Neanderthal nasal cavities and nostrils followed a very constant trend,” study lead author Costantino Busi, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Perugia, told Live Science via email. “Generally, they start out large, but over the course of evolution they get even bigger, and the last populations of this species have very large nostrils.”

One theory about Neanderthals’ large noses is that they had similarly large sinuses and strengthened airways that evolved as an adaptation to living in cold, dry environments. Their specialized nasal structures may have helped warm and humidify the air before it reached the lungs. However, all previous studies of Neanderthal nasal anatomy were based on approximations of the delicate bones within the nasal cavity. This is because these bones (ethmoid, vomer, and inferior turbinate) are broken or missing in all Neanderthal skulls discovered so far.

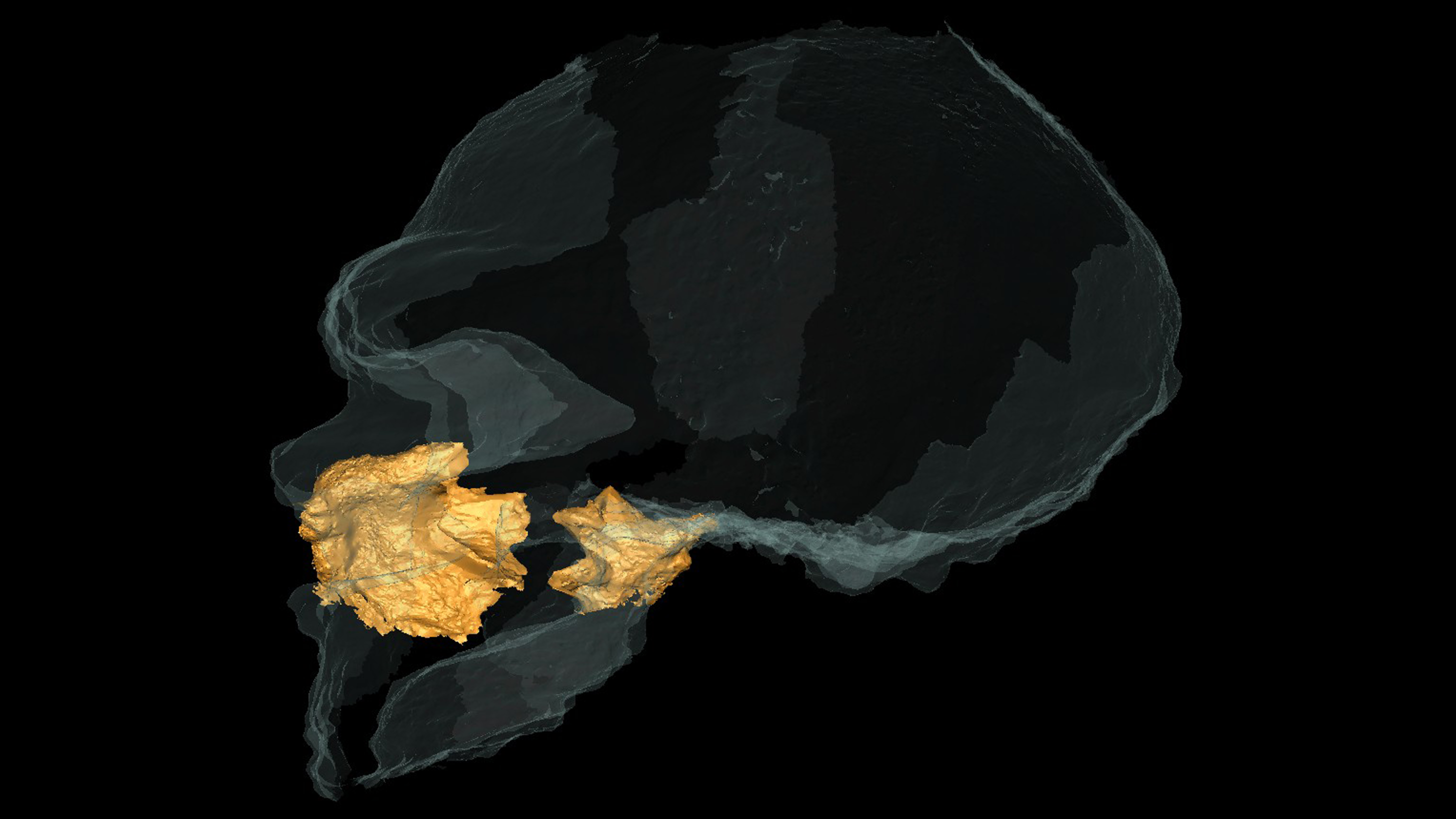

Bulli and his colleagues are working on a “virtual paleoanthropology” project to document and digitize the Altamura people without removing specimens from the caves. The researchers used an endoscopic probe to capture video from inside the nasal cavity of the skull, creating the first 3D photogrammetry model of a Neanderthal nasal bone.

Analyzing endoscopic images, researchers found that Altamura’s internal nasal structure was neither special nor substantially different from that of modern humans. The rest of the Neanderthal skeleton appeared to be adapted to the cold, with shorter limbs and a stockier build than modern humans, but not the nose.

Todd Ray, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Sussex who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that the new study is useful because “two of the three unique features of the Neanderthal nasal cavity previously proposed do not appear to be present in this specimen.” The lack of unique features “suggests that there is previously unknown species diversity,” Ray said.

Buj agreed that there was probably some intraspecific variation among Neanderthals, but cautioned that hard evidence for this variation is limited, as Altamura is the only one to provide evidence for the internal structure of the Neanderthal nose.

But the answer to why Neanderthals had big noses may have nothing to do with biological adaptation to cold climates, Ray says.

“All early Homo species have broad noses,” Ray said. “While most Homo sapiens have broad noses, only the Nordic/Arctic peoples do not, which is a small minority of species.”

Rather than viewing the Neanderthal nose as a unique adaptation to cold climates, it is better to understand it as an efficient way to vary the temperature and humidity of the inhaled air needed to power Neanderthals’ gigantic bodies. Buj said a number of environmental pressures and physical constraints likely helped shape Neanderthal faces, “resulting in a model that replaced our faces but was perfectly adapted to the harsh climate of the late Pleistocene of Europe.”

Neanderthal quiz: How much do you know about our closest relatives?

Source link